| Members of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander communities are advised that this text may contain names and images of deceased people. Readers should also be aware that certain words, terms or descriptions may be culturally insensitive and would almost certainly be considered inappropriate today, but may have reflected the author’s/creator’s attitude or that of the period in which they were written. |

The Peramangk aboriginal people have lived in The Adelaide Hills for at least 2,400 years |

|

Please be aware that some colonial diary entries recited here may contain material that, culturally speaking, is highly insensitive. It is reproduced here as it can save the reader having to find the original document in the case of each one cited, which can be laborious. The recited documents were generally each available on the internet. Additional information regarding the Peramangk is available from:

|

Introduction

Long before the dawn of modern white history, the Peramangk Aboriginal people inhabited the tree-filled gullies and park-like tablelands of the eastern Adelaide Hills. These folk enjoyed an unending supply of edible plants and grubs to gather, together with marsupials such as kangaroos and opossums to hunt. Seasonal trading occurred with the River Murray Aborigines, an association which occasionally led to war. By the time the first white colonists made their way into the Adelaide Hills in 1837, the Peramangk had all but disappeared, leaving great silent forests for Europeans to explore and eventually clear. Remnants of Aboriginal rock paintings and creek-side camps, together with strategic look-out caves peering out over the Murray Flats, remind later generations of this significant era.

Long before the dawn of modern white history, the Peramangk Aboriginal people inhabited the tree-filled gullies and park-like tablelands of the eastern Adelaide Hills. These folk enjoyed an unending supply of edible plants and grubs to gather, together with marsupials such as kangaroos and opossums to hunt. Seasonal trading occurred with the River Murray Aborigines, an association which occasionally led to war. By the time the first white colonists made their way into the Adelaide Hills in 1837, the Peramangk had all but disappeared, leaving great silent forests for Europeans to explore and eventually clear. Remnants of Aboriginal rock paintings and creek-side camps, together with strategic look-out caves peering out over the Murray Flats, remind later generations of this significant era.

The Peramangk habitat in South Australia ranged from the cool Eucalyptus forests of the Mount Lofty Summit region, often called 'The Tiers', to the warmer eastern ranges near the Murray Plains. Their territory extended from the south near Myponga, north towards Gawler. and then east along the South Para River to the township of Truro. Their eastern boundary extended from near Towitta and southwards towards Strathalbyn, following the Bremer escarpment. The northern Peramangk lived close to Mount Crawford and were known as the 'Tarrawata'. The Mount Barker Springs group were known as the 'Ngurlinjeri'. A splinter group of the Peramangk nation were known as the 'Merrimayanna', and lived in a semi-permanent campsite in the eastern Barossa Region.

The Peramangk habitat in South Australia ranged from the cool Eucalyptus forests of the Mount Lofty Summit region, often called 'The Tiers', to the warmer eastern ranges near the Murray Plains. Their territory extended from the south near Myponga, north towards Gawler. and then east along the South Para River to the township of Truro. Their eastern boundary extended from near Towitta and southwards towards Strathalbyn, following the Bremer escarpment. The northern Peramangk lived close to Mount Crawford and were known as the 'Tarrawata'. The Mount Barker Springs group were known as the 'Ngurlinjeri'. A splinter group of the Peramangk nation were known as the 'Merrimayanna', and lived in a semi-permanent campsite in the eastern Barossa Region.

The 'Merrimayanna' were known as skilled artists who painted vivid motifs in red, yellow and white ochre. They utilized the many rock shelters in the eastern ranges to depict probable dream time stories, ceremonies and hunting scenes. Of the 69 art sites recorded so far, some can be visited with Aboriginal custodians. Only some of the 'Merrimayanna' art works have been interpreted with many other sites yet to be discovered.

With the advancement of agricultural development, which displaced many Aboriginals and the spread of infectious diseases introduced by the Europeans the population of Aboriginal people declined dramatically. Very little documentation of the Peramangk people exists beyond the 1850s and it is thought those who remained integrated with the 'Ngarindjeri' of the lower Murray and the 'Kaurna' of the Adelaide plains.

Hahndorf

The site chosen by the Lutherans for the village of Hahndorf was a favourite summer camping place for the Peramangk Aboriginal people. The indigenous people called it 'Bukartilla' (in reference to the swimming hole). It was watered by several creeks emptying into the nearby Onkaparinga River. Groups of large gum trees existed with their centres deliberately fired to make a hollow area to provide temporary shelter whenever they were in residence.

[Note: The Peramangk Aborigines had two swimming places in Hahndorf. They were both near the main street, one next to Carl Nitschke Car Park and the other under the main road bridge at Alex Johnston Park. - Reg Butler]

Contrary to expectation, there are few records of conflict between the Peramangk and the Lutherans. They are recorded as showing the settlers how to catch possums and where to find edible roots and leaves but their kindness did not prevent loss of their hunting grounds.

In 1844, there is recorded a battle between the Permanangk people of the hills and the Moop-pol-tha-wong from the Murray and Encounter Bay regions. This occurred in the vicinity of Nixon's Mill at Hahndorf and involved some 2000 warriors. Intervention by the Mill owner and two other men by attempting to reason with the aboriginal leaders failed, and the episode was only ended when mounted troopers with drawn swords arrived.

Excerpts from Publications related to Hahndorf

-

1964 - Excerpts from Captain Hahn’s Diary translated by Dr Blaess and Dr Triebe, South Australiana, Vol 111, No2, Sept 1964, SA Libraries Board.

Description of the Hahndorf site: “My first glance fell on beautifully formed trees, which nature had planted there as with the hands of a gardener –the beautiful long grass wet with dew coloured the ground a lovely green; from the several big trees standing majestically, wild birds flitted from branch to branch, cockatoos, parrots and parakeets etc warbling their varied tones. Description of indigenous people: “A few of them might have a kangaroo skin wrapped around them to cover their nakedness. Smallpox must often rage among them as most carry thick scars from it." "I saw there a jacket which had been put together only from the skins of small opossums by an aboriginal woman. It was so beautifully sewn that few European women could do better. If you consider the tools with which the job was done, it deserves greater admiration. The thread had been made from kangaroo gut. A small bone sharpened to a point at one end served instead of a needle.” “These people seem very good-natured, at least those living in the region of the Onkaparinga River. The general opinion is that beyond the Murray they are less well-disposed. If they are not provoked they don’t harm any human being.” -

1926 - Hossfeld, Paul S. The Aborigines of South Australia: Native occupation of Eden Valley and Angaston, Royal Society of SA.

This paper would be incomplete without reference to the very numerous burnt out hollow red gums occurring in the district. The majority of the openings face east or north, and provide excellent shelter……..In conclusion the writer voices his regret that these important records of the former native occupation should be doomed to rapid disappearance owing to the mutilation which they are subject to by visitors ignorant of their value. -

1975 - Wittwer E. Allan. Liebelt Family History, Liebelt Family Committee. Quote from interview with Johann Christoph LIEBELT

We left Hamburg in the ship Zebra under the command of Captain Hahn in 1838 and arrived at Port Adelaide after 17 weeks voyage …….. The country around what is now known as Hahndorf had just been surveyed …… Each family taking up land had to be responsible for the price, Viz 7 pounds and acre which eventually we were able to pay off. At first our principle means of subsistence were buttercup roots which we had to grub out with our hands, and opossums, the catching of which we learnt from the blacks.” “The area occupied by the town formed part of an old cattle station or maybe even a holding camp for the cattle driven overland from Sydney and Melbourne by overlanders. -

“Johann Christian LIEBELT and his family were pioneer settlers of Hahndorf. (Anni Luur Fox - Nov 1998)

Christian was allocated 4.25 acres of land in the new village. Christian built his humble home of wattle and daub on the property. It consisted of two rooms and a porch. In addition, a cellar of similar construction was built somewhat removed from the house. In the door of the old homestead was a spear mark where a spear stuck in the door after an Aborigine had thrown it at Maria Elisabeth as she fled into the house. She only just made it to safety.

Excerpt from 'Torrens Valley Historical Journal' Number 32

"The Peramangk occupied an area which was well endowed with resources, food, water, firewood, and raw materials such as stone; timber and resins for tool manufacture; bark for huts, shields and canoes; pigments for painting; furred animals for warm rugs, etc. During winter, they constructed warm, dry huts of branches, bark grass and leaves, often built around the hollow side of old red gums.

"The Peramangk occupied an area which was well endowed with resources, food, water, firewood, and raw materials such as stone; timber and resins for tool manufacture; bark for huts, shields and canoes; pigments for painting; furred animals for warm rugs, etc. During winter, they constructed warm, dry huts of branches, bark grass and leaves, often built around the hollow side of old red gums.

They were encountered by European explorers, squatters and overlanders who passed through this area or settled there. Sometimes they visited the settlement of Adelaide in a large group to conduct ceremonial business and social gatherings, and no doubt to observe the strange appearance, habits and artifacts of the European interlopers. This contact was mostly peaceful, although the European police troopers did harass them on occasion. Not until the mid 1840's, when flocks of sheep were crowding the watering places and grazing lands of the "Hills tribe" and the animals which they hunted for food, did open conflicts arise. Even then, the source of confrontation was the right of local Aborigines to take for their own use some of the animals and material goods which the Europeans had placed on their traditional lands. There was apparently little physical violence, and in some cases food and other items were given by farmers in exchange for assistance with harvesting crops (eg wheat and potatoes), at a time when farm labour was in desperately short supply.

However, by the late 1850's the scattered documentary sources cease to mention the Hills tribe; there is only the chronicle of a growing agricultural district. Only fragmentary descriptions have been recorded of the traditional way of life of the Peramangk. This is a sad commentary on the devastating effect of European incursions upon Aboriginal Australia.

Most of the historical information relating to the Peramangk consists of passing references in European diaries, official's records, or personal memoirs. They are barely mentioned in the early ethnographic literature concerning Aborigines, written in the late nineteenth century."

Historical Notes

The Peramangk were an 'Indigenous Australian' people whose traditional lands were primarily located in Adelaide Hills but also in the southern stretches of the Fleurieu Peninsula, South Australia. They were also referred to as the Mount Barker, South Australia tribe, as their numbers were noted to be greater around the Mount Barker summit (ref: http://www.desertdreams.com.au ), but Peramangk country extended from the Barossa Valley in the north, south to Myponga, South Australia, east to Strathalbyn, and west to the Gulf St Vincent.

The Peramangk were an 'Indigenous Australian' people whose traditional lands were primarily located in Adelaide Hills but also in the southern stretches of the Fleurieu Peninsula, South Australia. They were also referred to as the Mount Barker, South Australia tribe, as their numbers were noted to be greater around the Mount Barker summit (ref: http://www.desertdreams.com.au ), but Peramangk country extended from the Barossa Valley in the north, south to Myponga, South Australia, east to Strathalbyn, and west to the Gulf St Vincent.

Peramangk family group names included Poonawatta, Tarrawatta, Karrawatta, Yira-Ruka, Wiljani, Mutingengal, Runganng, Jolori, Pongarang, Paldarinalwar, Merelda. They did not become extinct, and many families can trace connections back to several survivors. Art works were being maintained well into the 20th century. Norman Tindale in his various interviews with Peramangk descendents recorded the names of at least 8 family groups; the Poonawatta to the west of Mt Crawford, the Tarrawatta and Yira-Ruka (Wiljani)whose worta (lands) extended to the east down as far as Mt Torrens and Mannum. The Karrawatta (west) and Mutingengal(Mareldi) (east), occupied lands to the north of Mt Barker, but somewhat south of the River Torrens. The Rungang (Jolori), Pongarang (Paldarinalwar), and the Merelda, occupied the lands to the south of Mt Barker, in preceding order down as far as Myponga in the south.

(ref: http://www.samuseum.sa.gov.au/ | Tindale Tribes | Peramangk | )

Conflicting reports show enmity between the three tribes of the Adelaide region, Kaurna, Ngarrindjeri and Peramangk, yet other reports tell that the Peramangk were held with some reverence due to their differing cultural practices.

(ref: http://www.samuseum.sa.gov.au/ |Tindale Tribes | Peramangk | )

Population and traditional practises are hard to verify as shortly after the European settlement of the Adelaide Hills, especially in Mount Barker, and Hahndorf, the Peramangk had been thought to have been wiped out by introduced diseases, but records show that they were in fact settled at Poonindee, Moorundie, Wellington, and later at Point Pearce and Point McLeay.

(ref: Poonindie, Brock P & Kartinyeri D (1989), Aboriginal Heritage Branch, S.A. Government Printer, Adelaide; and Hahndorf - Settlement and the Early Village)

Peramangk family group names included Poonawatta, Tarrawatta, Karrawatta, Yira-Ruka, Wiljani, Mutingengal, Runganng, Jolori, Pongarang, Paldarinalwar, Merelda. They did not become extinct, and many families can trace connections back to several survivors. Art works were being maintained well into the 20th century.

(ref: Hancock,D. 1997, An Archaeological report on a Peramangk Aboriginal location near Springton South Australia, Flinders University.)

1842 - South Australia, in 1842 By One Who Lived There Nearly Four Years. Published by J.C. Hailes 1843

‘From the time of the founding of the colony of South Australia, great interest has been felt in behalf of the native inhabitants of the country……The boundaries of their particular districts are well known by the different tribes and generally respected by them; something of of the nature of hereditry succession obtains among them, so that they have in their language a term “pangkarra” which signifies a district or tract of country belonging to an individual which he inherits from his father’. Each “pangkarra” has its peculiar name; and as in the civilised world the owners take their names from their lands, so the natives do in South Australia with the addition of the term “burka”. One popular character in Adelaide is known by the regal title of “King John”….. his native name was “Mullawirraburka”, signifying “The Dry-forest Man”.

1926 - Hossfeld, Paul S. The Aborigines of South Australia: Native occupation of Eden Valley and Angaston, Royal Society of SA.

“This paper would be incomplete without reference to the very numerous burnt out hollow red gums occurring in the district. The majority of the openings face east or north, and provide excellent shelter……..In conclusion the writer voices his regret that these important records of the former native occupation should be doomed to rapid disappearance owing to the mutilation which they are subject to by visitors ignorant of their value.”

Peramangk Language

The Peramangk appears to have belonged to the Yura-Thura group of languages as described by Luis Hercuse, in A Nukunu Dictionary 1992, AIATSIS. Tindale when interviewing Robert 'Tarby' Mason, learnt that the language of the Peramangk was related not only to that of the groups east of the river, but to the groups as far north as Lake Victoria. This put them in close contact with the Nganguruku, Ngaiwang, Ngadjuri and Maraura peoples. Hemming, S. & Cook, C. Crossing the River,Murray-darling basin Commision (1992). There are several Peramangk words recorded in a variety of sources; - ku:itpo - sacred or forbidden place; - maitpana:likkya - food for them ( a ration station near Mt Barker); -poona: good / healthy / fertile (poonawatta - Lyndoch Valley); - watta (worta): a persons land or country; - tarra: land that rises up, a steep hill or ridge; - karra: redgum (same as in the Kaurna); - kungatukko: womens look out ( in Peramangk a hard TT sound is sometimes; replaced with a hard KK sound instead); - wadnar: digging or climbing stick; - kakirra: moon; - nurrondi: enchant/charm; - meyuworta (meruwatta): countryman/ a person belonging to the same family group; - marnitti: grease to mix with ochre to cover the body; - mambarti: hair matted with grease and red ochre; - kuyeta: first born son; - kartiatto: first born daughter; - yarida: bad magic; - lantara: ghost or spirit; - tinda: a persons totem ;

( ref: - Teichelmann, CG & Schurmann, C.W. Outlines of a grammar.....of the language of South Australia....around Adelaide, (1840), by authors. - Hemming & Cook,Crossing the River (1992) )

Aboriginal Rock Art in the Adelaide Hills (Robin Coles)

Robin Coles with Aboriginal Students at Mt Lofty Rock Art site.The recently published book ‘Peramangk culture and rock art in the Mt Lofty Ranges of SA’, written by Robin Coles covers the known history of the Peramangk and their culture, myths and legends, use of fungi and plants, and their rock art in the Mount Lofty ranges, and includes over 160 colour pictures.

Robin Coles with Aboriginal Students at Mt Lofty Rock Art site.The recently published book ‘Peramangk culture and rock art in the Mt Lofty Ranges of SA’, written by Robin Coles covers the known history of the Peramangk and their culture, myths and legends, use of fungi and plants, and their rock art in the Mount Lofty ranges, and includes over 160 colour pictures.

Also included are images of some of the 69 discovered rock art paintings and engravings in the Mt Lofty Ranges, the stories behind the art, and historical information on how the Peramangk people lived.

Robin Coles, Senior Consultant at Rural Solutions SA, spent more than 20 years of discovering and photographing Aboriginal rock art in the Mount Lofty Ranges. What started out as a regular Sunday drive through the Mt Lofty Ranges became much more for Robin, whose interest in the relatively unknown Peramangk culture prompted him to document the remaining heritage for future generations.

Robin, who also conducts Workers Education Association tours to some of the rock art sites, says there is very little knowledge of what the paintings mean as much of the generational story telling stopped after the 1860s when the Aboriginal people were encouraged to adopt Christianity.

Robin has stated that -

-

We only know about five to ten per cent of what these paintings represent, which is why it’s important to document this cultural heritage and educate future generations before it is too late.

-

Some of the paintings may be 2500 years old, and were probably used to depict their culture and spiritual beliefs in the land and dreamtime stories.

-

They also acted as territorial markers and information centres for teaching. Just as we have our tourism information centres, these people had them lined up for people visiting from the east. There were also well known trade routes between the Murray and the Hills.

The book was based on research that was funded through grants administered by the Aboriginal Heritage Branch with assistance from the Peramangk Elder, the late Richard Hunter, and Isobelle Campbell (Peramangk custodian and President Mannum Aboriginal Development Committee).

People Of The Adelaide Hills - by Reg Butler

(The following was extracted from information by Reg Butler provided to local Schools)

Look! High above the swirling white winter mists rise huge mountains covered with dark stringybark trees. In summer, night bushfires sometimes crackle and glow red among the branches. The is the former homeland of the Peramangk people.

Here is their story ...............

| Many years ago, the first Aboriginal people came to live on the Adelaide Plains. Sadly, evil spirits which lived there did not like to be disturbed. They changed many of the new-comers into animals and birds. Eventually, the Aborigines forced the evil spirits to remain in creeks and waterholes forever. However, Aboriginal people could no longer eat animals or birds, because, very likely, they could be human beings. One man and his wife ate part of a kangaroo. Some time later, their little baby boy, Pootpobberrie, was born. He was part person and part kangaroo. Pootpobberie grew taller than anyone else. He had long pointed paws and fur grew all over him. Pootpobberrie could carry a rock in one hand and jump across a gully with one leap as well. In time, Pootpobberrie and his wife went to live in the Adelaide Hills. They became the father and mother of the Peramangk people. |

European immigrants drawing near by sea to South Australia in the late 1830s occasionally became aware of the Peramangk people, long before knowing anything about them. During February 1837, Pastor William Finlayson and his fellow passengers gazed over the side of the good ship John Renwick about to ride at anchor at Glenelg after nightfall:

The watchers on deck beheld a fire on one of the hills, which seemed to spread from hill to hill with amazing speed. All on board were now awake and on deck looking at this grand conflagration, as it seemed as if the whole land was a mass of flame. In the morning, a great change had taken place; the whole range was a black as midnight, except where the trees were burning ...

Next morning, the curious minister found out from people ashore that towards the end of summer, the Peramangk people used to set alight to the dry grass to drive out and catch all manner of animals and vermin trying to escape the flames.

Nearly two years later, on his journey into the Adelaide Hills to find a permanent home for his Lutheran refugees, Captain Hahn witnessed how the Aborigines did the burning:

But this involves a whole tribe. They form a circle about twenty English miles in diameter, light fires around this area, and then direct the fire closer and closer in toward the centre of the circle. The long dry grass, bushes and young trees burn fiercely; all the animals living in this area flee toward the centre, where the savages then catch them. A hunt like this occurred during our stay, and the fire burned for some days; I had never before seen such a fire.

For his part, Pastor Finlayson never forgot his first vivid glimpse of Peramangk Aboriginal activity. As he established a farm at what is now known as Mitcham, he promised himself to make a trip into a region where practically no Europeans had ventured. Finlayson joined three other adventurers to push right across Peramangk territory during Christmas 1837. On 26 December, the party stood on the Mount Barker sunnit and then, by following the course of the Bremer River, struggled down the slopes to Lake Alexandrina. Tired and footsore, Finlayson and his companions returned home on New Year’s Eve 1838:

Some in Adelaide thought we would never return, but be murdered by the natives, but, strange to say ... we never saw one ... Smoke in the distance we frequently saw, and came upon their recently occupied camping-places, but themseles we saw not, but I have no doubt they saw and avoided us.

Yes, the Peramangk people would have certainly been on guard! Today, rock lookout shelters still stand sentinal over the Adelaide Plains and the Murray Flats. The feared Peramangk were always watchful for Kaurna and Murray River Aborigines about to enter the ranges, via one of the numerous river valleys. These lookouts also served as bases to send smoke signals to other tribal groups and to spot game which hunters could later seek out to vary the diet of hills dwellers.

Ongoing flood damage and careful search have revealed more and more sites where visiting groups from the plains camped on journeys in and out of the mountains. Well along the South Rhine gorge east from Eden Valley, for example, a campsite for some four hundred travellers has been discovered. During such epic trips, the visitors hoped to bargain for canoe bark, possum skins and quartz.

In return, the Murray tribe brought up flint from cliffs along the river, red ochre gathered from in the vicinity of the Reedy Creek mine near present-day Palmer and deft, light spears made from mallee wood.

For millenia, Peramangk Aborigines had called the Adelaide Hills home. These people learnt to survive in a climate often freezing in winter and rather warm in summer. Short, though violent, spring and summer thunderstorms followed sustained winter deluges of rain. Particularly on the eastern ranges, lightning strikes burnt out huge tree trunks and swept through vegetation, augmented periodically by human firesticks when nature failed to oblige. The Aborigines used the hollow gums for shelter and hunted down wild creatures fleeing into the open to escape advancing flames. All living things alike recognised the dangers of remaining anywhere near watercourses about to burst into wild, uncontrolled flooding, which subsided as fast as it had occurred.

Although not now known exactly, the Peramangk lived in a region with definite borders against the Kaurna tribe of the Adelaide Plains to the west and the Murray River tribes to the east. Tindale believed that the name Peramangk could well have been of Kaurna origin, though, meaning flesh of red colour, harking back to the tribal custom of covering males with ochre at times of initiation and war. Just outside of the Mount Pleasant district, the Angas family's Tarrawatta Station near Angaston preserves the name of one of the local groups of Peramangk. A corruption of the Aboriginal word tainkila, meaning ghost moth grub, remains in Tungkillo, well-known as a regional name to every resident of the Mount Pleasant area itself.

Unfortunately, conflicting evidence makes reliable commentary upon Mount Pleasant's original Aboriginal inhabitants as difficult as tracing the area's geological formation. We owe a debt to diary observations of pioneer teacher and writer WA Cawthorne, in the 1840s; to detailed studies by the scholar NB Tindale between the 1920s-1970s; to interviews and investigations conducted in the 1920s by Paul Hossfeld, a Lutheran Pastor's son born and bred within coo-ee of the Murray Flats. Further scattered information emerges from the diaries and letters of the earliest colonists, who had fleeting contact with the Peramangk, before the tribe finally left its traditional grounds.

The caterpillar of the moth grub was a right royal delicacy for the Peramangk. Food gatherers became experts at flushing out these 8cm-10cm long balls of cream flesh from decaying gum trees. Tungkillo's prolific wattles proved another rich source of moth larvae. Further springtime treats included white ant and other insect larvae, birds' eggs, young birds and lizards. During summer, the tribe sought out native roots and vegetable products. Never did the Aborigines farm in the accepted European method.

At other times of the year, animal hunting took precedence. Digging implements or smoke forced bandicoots and other burrowing creatures out of their holes. Food-baited grass snares caught Murray Flats rats. Small sticks burnt holes in the bark of bare lower tree trunks to allow hunters to climb up to raid the upper branches for possums, valuable for both skin and meat. Using only a slender spear and short club, Peramangk men pitted their wits against kangaroos, wallabies, possums and emus - either driving them into huge nets made from woven bulrushes, or spearing and clubbing unsuspecting creatures intent upon an evening drink at one of the area's numberless waterholes. The water also yielded yabbies, perch, mud fish and water rats.

Even though the climate could be harsh, the Peramangk had a wealth of natural resources to help make life comfortable and to trade with their neighbours upon the plains. Hossfeld found out from Mrs William Grigg, of Springton, that Aborigines tended to gather in numbers of about six hundred in semi-permanent camps at the headwaters of the various district rivers. During her childhood on Pewsey Vale Station in the 1840s, the former Miss Isabella Semple had watched the Peramangk abandon their warm winter homes of branches and bark, grass and leaves built around hollow-sided red gums to enjoy an outdoors existence as spring advanced, in wurlies constructed of huge sheets of bark. From time to time, small groups spent days on walk-about, hunting and gathering over a wide area in the balmy summer weather, when substantial protection was not usually a necessity.

Over the years, the Peramangk worked out a watchful co-existence with their war-like neighbours along the Murray River. Lookout shelters, fashioned under convenient overhanging rocks with excellent protection against wind and rain, have survived on high portions of the Tungkillo Ranges and the Rhine Hills. From here, the Mount Pleasant Aborigines had an unimpeded view of advancing natives crossing the Murray Flats to bargain for canoe bark, possum skins and quartz. The lookouts also served as bases to send smoke signals to other tribal groups and to spot game which hunters could later seek out to vary the diet of the hills dwellers.

In return, the Murray tribe brought up flint from cliffs along the river, red ochre gathered from in the vicinity of the Reedy Creek mine and deft, light spears made from mallee wood. A journey into the ranges assumed trappings of the epic - Palmer residents long pointed out a huge red gum growing at the rear of Henry Mengersen’s garden, where Aboriginal people gathered and camped on their way in and out of the nearby gorges. Well along the South Rhine gorge, a campsite for some four hundred travellers has been discovered.

Apparently, the Murray Aborigines lived in just as much fear of their mountain-dwelling neighbours. The closed-in forests and hills, where humans appeared to flit in shadowy form, did not appeal to a folk who spent their existence in open countryside. Even when the Peramangk had vanished from the region, the visiting Murray people still laid barter goods in appropriate bushland clearings in order to appease any malevolent influences. It also seems evident that both groups disliked the silent stringybark forests and kept well away from gum trees in summer, when boughs dropped without explanation and could cause great damage to humans and property caught unawares beneath.

Residents and others with sympathy for the Mount Pleasant district's Aboriginal past have long had unrivalled opportunity to hone their interest. People of late middle-age and older (1993) who spent their youth in the South Rhine and Tungkillo countryside have vivid memories of discovering Aboriginal campsites at intervals along some of the creeks and rivers. With the aid of the inevitable campfire, Peramangk women cooked food, while men used the heat to fashion certain weapons. At night, the low embers provided light and warmth. Some amateur anthropologists have found Aboriginal burial grounds uncovered by rabbits and/or flood water in the soft ground beside streams and waterholes. Following a death, the tribal women engaged in a tremendous communal howling around the corpse, after which they they wrapped the body and buried it in a carefully-made hole where digging was easy. Effective modern flood and rabbit controls will make the discovery of further new Aboriginal campsites and burial grounds rather more difficult.

Property owners, hikers and picnickers have come across caves with Aboriginal paintings in the steep Tungkillo and Rhine gorges, often in fairly inaccessible countryside. For fear of vandalism, some of these sites have not been advertised and the entrances protected from easy access. Peramangk artists moulded chewed eucalyptus leaves into brushes and painted designs in red ochre, or occasionally white clay, on the cave roof and walls. Most of the pictures show human beings in conventional positions; while others are footprints, or depict lizards, snakes and turtles, all creatures abounding in the neighbourhood. The caves had particular significance for initiation ceremonies of youths approaching adulthood and for the rites of the tribal sorcerer, who professed to be able to cure sickness, control the elements, cast spells and change themselves into other objects. Needless to say, the tribe venerated both the sorcerer and the caves and stayed well away, unless absolutely necessary.

Even before white settlers first moved to the Mount Pleasant area in the early 1840s, it appears that the Peramangk had voluntarily vacated much of their original territory. Various European influences quickly broke down the remainder of the carefully-balanced discipline which had nurtured Aboriginal life in the region. Farms and sheep stations obliterated traditional paths and made it difficult for the Peramangk to gather in particular spots to carry out rituals. Foreign disease wrought havoc amongst people with no natural resistance to imported sickness. In 1842, an English colonist wrote home to describe a native encampment he had seen in Flaxman Valley:

The blacks wander about in the day-time, and at night sleep in a shed, which they call a whurley (sic), made of the branches of trees ... I can hear them singing one of their carrobarees (sic) ... about 100 yards distant from the door. I went the other night to see them and found them all sitting stark naked around the fire ... They had been feasting on the fat of a bullock, which we had given them ... We found a large lizard beside them, which they had put by for their next meal. They are not, generally, very communicative, as they suspect the white men; but this family appear to be an exception to such reservedness; and I learnt several native words from them.

Aboriginal people hovered in an uneasy half-real world. They learnt some words of broken English and increasingly relied on the whites for food and other handouts. A few Aborigines became stockmen on the recently-established pastoral runs, while the womenfolk found employment in domestic work. Most remained wanderers (their beloved puppies peering out inquisitively from swinging billies), well-remembered for an annual visit to the Mount Pleasant region, while on their way back and forth between the Adelaide Plains and the Murray River until probably the 1870s. No recorded incident of violent opposition to European settlement in the district has so far come to light. The Peramangk apparently melted before the coming of the white folk, whom they often regarded as ghostly re-incarnations of their own ancestors.

Mrs Lucy Coleman, who arrived in the Mount Barker District in the late 1830s, remembered a blind member of the Mount Barker tribe climbing high trees:

He was most clever at climbing trees to get opossums and young parrots. With one stroke of his pointed stick he would cut a deep step in the bark of a tree, and into it would put the great toe of his right foot. Then another step was cut higher up into which the toe of his left foot was put, and a pointed stick in his left hand, driven into the bark, held him up whilst this was done. In that way, he would quickly mount up to the branches of a tall gum tree. I have myself seen that man go up a smooth-barked gum tree which was at least 30’ high to the nearest branch.

His wife or daughter would stand under the tree, and tell him which way to turn to a branch that was hollow at the end. He would then carefully creep along it until he was near enough to put in his arm and pull out the opossums or young parrots that were inside, and throw them down to those below.

Sadly, the poor man fell to his death during one of these climbing feats. Mrs Coleman’s brother helped the widow dig a grave for the brave hunter.

The Peramangk Aborigines - By Reg Butler

European immigrants drawing near by sea to South Australia in the late 1830s occasionally became aware of the Peramangk people, long before knowing anything about them. After nightfall on 10 February 1837, Pastor William Finlayson and his fellow passengers gazed over the side of the good ship John Renwick about to ride at anchor at Glenelg :

The watchers on deck beheld a fire on one of the hills, which seemed to spread from hill to hill with amazing speed. All on board were now awake and on deck looking at this grand conflagration, as it seemed as if the whole land was a mass of flame. In the morning, a great change had taken place; the whole range was as black as midnight, except where the trees were burning...

Next morning, the curious minister went ashore. He found out that towards the end of each summer, the Peramangk people used to set alight to the dry grass to drive out and catch all manner of animals and vermin trying to escape the flames.

Nearly two years later, on his journey into the Adelaide Hills to find a permanent home for his Prussian Lutheran refugees, Captain Hahn witnessed how the Aborigines did the burning:

But this involves a whole tribe. They form a circle about twenty English miles in diameter, light fires around this area, and then direct the fire closer and closer in toward the centre of the circle. The long dry grass, bushes and young trees burn fiercely; all the animals living in this area flee toward the centre, where the savages then catch them. A hunt like this occurred during our stay, and the fire burned for some days; I had never before seen such a fire.

For his part, Pastor Finlayson never forgot his first vivid glimpse of Peramangk Aboriginal activity. As he established a farm at what is now known as Mitcham, he promised himself to make a trip into a region where practically no Europeans had ventured. Finlayson joined three other adventurers to push right across the heart of Peramangk territory during Christmas 1837. On 26 December, the party stood on the Mount Barker summit, and then, by following the course of the Bremer River, struggled down rough slopes to Lake Alexandrina . Tired and footsore, William Finlayson and his companions returned home on New Year’s Eve 1838:

Some in Adelaide thought we would never return, but be murdered by the natives, but, strange to say...we never saw one... Smoke in the distance we frequently saw, and came upon their recently occupied camping-places, but themseles we saw not, but I have no doubt they saw and avoided us.

Yes, the Peramangk people would have certainly been on guard! Today, rock lookout shelters still stand sentinal over the Adelaide Plains and the Murray Flats. The fearful Peramangk were always watchful for Kaurna and Murray River Aborigines about to enter the ranges, via one of the numerous river valleys. These lookouts also served as bases to send smoke signals to other tribal groups and to spot game which hunters could later seek out to vary the diet of hills dwellers.

Ongoing flood damage and careful search have revealed more and more sites where visiting groups from the plains camped on journeys in and out of the mountains. Well along the South Rhine gorge east from Eden Valley, for example, a campsite for some four hundred travellers has been discovered. During such epic trips, the visitors hoped to bargain for canoe bark, possum skins and quartz.

In return, the Murray groups brought up flint from cliffs along the river, red ochre gathered from in the vicinity of the Reedy Creek Mine near present-day Palmer and deft, light spears made from mallee wood.

Apparently, the Kaurna and Murray Aborigines lived in just as much fear of their mountain-dwelling neighbours. The closed-in forests and hills, where humans appeared to flit in shadowy form, did not appeal to folk who spent their existence in open countryside. Even when the Peramangk had vanished from the region, visiting Aborigines still laid barter goods in appropriate bushland clearings in order to appease any malevolent influences. It also appears that even the Peramangk also disliked the silent stringybark mountaintop forests and kept well away from gum trees in summer, when boughs dropped without explanation and could cause great damage to humans and property caught unawares beneath.

For millenia, Peramangk Aborigines had called the Adelaide Hills home. These people learnt to survive in a climate often freezing in winter and rather warm in summer. Short, though violent, spring and summer thunderstorms followed sustained winter deluges of rain. Particularly on the eastern ranges, lightning strikes burnt out huge tree trunks and swept through vegetation, augmented periodically by human firesticks when nature failed to oblige. The Aborigines used the hollow gums for shelter and hunted down wild creatures fleeing into the open to escape advancing flames. All living things alike recognised the dangers of remaining anywhere near watercourses about to burst into wild, uncontrolled flooding, which subsided as fast as it had occurred.

Unfortunately, conflicting evidence makes reliable commentary upon the Adelaide Hill's original Aboriginal inhabitants as difficult as tracing the area's geological formation. We owe a debt to diary observations of pioneer teacher and writer WA Cawthorne, in the 1840s; to detailed studies by the scholar NB Tindale between the 1920s-1970s; to interviews and investigations conducted in the 1920s by Paul Hossfeld, a Lutheran Pastor's son born and bred within coo-ee of the Murray Flats. Further scattered information emerges from the diaries and letters of the earliest colonists, who had fleeting contact with the Peramangk, before the tribe finally left its traditional grounds.

Although not now known exactly, the Peramangk lived in a region with definite borders against the Kaurna people of the Adelaide Plains to the west and the Murray River tribes to the east. Tindale believed that the name Peramangk could well have been of Kaurna origin, though, meaning flesh of red colour, harking back to the tribal custom of covering males with ochre at times of initiation and war. The JH Angas family's Tarrawatta Station near Angaston preserves the name of one of the local groups of Peramangk. A corruption of the Aboriginal word tainkila, meaning ghost moth grub, remains in Tungkillo, well-known as a regional name to every resident of the Mount Pleasant area itself.

The caterpillar of the moth grub was a right royal delicacy for the Peramangk. Food gatherers became experts at flushing out these 8cm-10cm long balls of cream flesh from decaying gum trees. prolific stands of wattles scattered throughout the Adelaide Hills proved another rich source of moth larvae. Further springtime treats included white ant and other insect larvae, birds' eggs, young birds and lizards. During summer, the tribe sought out native roots and vegetable products. Never did the Aborigines farm in the accepted European method.

At other times of the year, animal hunting took precedence. Digging implements or smoke forced bandicoots and other burrowing creatures out of their holes. Food-baited grass snares caught Murray Flats rats. Small sticks burnt holes in the bark of bare lower tree trunks to allow hunters to climb up to raid the upper branches for possums, valuable for both skin and meat; Pastor Finlayson laughed hugely to see women scrambling agily after these furry creatures near the headwaters of Brownhill Creek. Mrs Lucy Coleman, who arrived in the Mount Barker District in the late 1830s, remembered a blind member of the Mount Barker tribe climbing high trees:

He was most clever at climbing trees to get opossums and young parrots. With one stroke of his pointed stick he would cut a deep step in the bark of a tree, and into it would put the great toe of his right foot. Then another step was cut higher up into which the toe of his left foot was put, and a pointed stick in his left hand, driven into the bark, held him up whilst this was done. In that way, he would quickly mount up to the branches of a tall gum tree. I have myself seen that man go up a smooth-barked gum tree which was at least 30’ high to the nearest branch.

His wife or daughter would stand under the tree, and tell him which way to turn to a branch that was hollow at the end. He would then carefully creep along it until he was near enough to put in his arm and pull out the opossums or young parrots that were inside, and throw them down to those below.

Sadly, the poor man fell to his death during one of these climbing feats. Mrs Coleman’s brother helped the widow dig a grave for the brave hunter.

Using only a slender spear and short club, Peramangk men pitted their wits against kangaroos, wallabies, possums and emus - either driving them into huge nets made from woven bulrushes, or spearing and clubbing unsuspecting creatures intent upon an evening drink at one of the Adelaide Hill's numberless waterholes. The water also yielded yabbies, perch, mud fish and water rats.

Even though the climate could be harsh, the Peramangk had a wealth of natural resources to help make life comfortable and to trade with their neighbours upon the plains. Hossfeld found out from Mrs William Grigg, of Springton, that Aborigines tended to gather in numbers of about six hundred in semi-permanent camps at the headwaters of the various Adelaide Hills streams - such as the Angas, the Bremer, the Torrens, the Onkaparinga and Mount Barker Creek. During her childhood on Pewsey Vale Station in the 1840s, the former Miss Isabella Semple had watched the Peramangk abandon their warm winter homes of branches and bark, grass and leaves built around hollow-sided red gums to enjoy an outdoors existence as spring advanced, in wurlies constructed of huge sheets of bark. From time to time, small groups spent days on walk-about, hunting and gathering over a wide area in the balmy summer weather, when substantial protection was not usually a necessity.

Residents and others with sympathy for the Mount Pleasant district's Aboriginal past have long had unrivalled opportunity to hone their interest. People of late middle-age and older (1993) who spent their youth in the South Rhine and Tungkillo countryside have vivid memories of discovering Aboriginal campsites at intervals along some of the creeks and rivers. With the aid of the inevitable campfire, Peramangk women cooked food, while men used the heat to fashion certain weapons. At night, the low embers provided light and warmth. Some amateur anthropologists have found Aboriginal burial grounds uncovered by rabbits and/or flood water in the soft ground beside streams and waterholes. Following a death, the tribal women engaged in a tremendous communal howling around the corpse, after which they they wrapped the body and buried it in a carefully-made hole where digging was easy. Effective modern flood and rabbit controls will make the discovery of further new Aboriginal campsites and burial grounds rather more difficult.

Property owners, hikers and picnickers have come across caves with Aboriginal paintings in the steep Tungkillo and Rhine gorges, often in fairly inaccessible countryside. For fear of vandalism, some of these sites have not been advertised and the entrances protected from easy access. Peramangk artists moulded chewed eucalyptus leaves into brushes and painted designs in red ochre, or occasionally white clay, on the cave roof and walls. Most of the pictures show human beings in conventional positions; while others are footprints, or depict lizards, snakes and turtles, all creatures abounding in the neighbourhood. The caves had particular significance for initiation ceremonies of youths approaching adulthood and for the rites of the tribal sorcerer, who professed to be able to cure sickness, control the elements, cast spells and change themselves into other objects. Needless to say, the tribe venerated both the sorcerer and the caves and stayed well away, unless absolutely necessary.

Even before white settlers first moved to the Mount Pleasant area in the early 1840s, it appears that the Peramangk had voluntarily vacated much of their original territory. Various European influences quickly broke down the remainder of the carefully-balanced discipline which had nurtured Aboriginal life in the region. Farms and sheep stations obliterated traditional paths and made it difficult for the Peramangk to gather in particular spots to carry out rituals. Foreign disease wrought havoc amongst people with no natural resistance to imported sickness. In 1842, an English colonist wrote home to describe a native encampment he had seen in Flaxman Valley:

The blacks wander about in the day-time, and at night sleep in a shed, which they call a whurley (sic), made of the branches of trees... I can hear them singing one of their carrobarees (sic)... about 100 yards distant from the door. I went the other night to see them and found them all sitting stark naked around the fire... They had been feasting on the fat of a bullock, which we had given them... We found a large lizard beside them, which they had put by for their next meal. They are not, generally, very communicative, as they suspect the white men; but this family appear to be an exception to such reservedness; and I learnt several native words from them.

Aboriginal people hovered in an uneasy half-real world. They learnt some words of broken English and increasingly relied on the whites for food and other handouts. A few Aborigines became stockmen on the recently-established pastoral runs, while the womenfolk found employment in domestic work. Most remained wanderers (their beloved puppies peering out inquisitively from swinging billies), well-remembered for an annual visit to the Mount Pleasant region, while on their way back and forth between the Adelaide Plains and the Murray River until probably the 1870s. No recorded incident of violent opposition to European settlement in the district has so far come to light. The Peramangk apparently melted before the coming of the white folk, whom they often regarded as ghostly re-incarnations of their own ancestors.

Bibliography

Compiled by Reg Butler (1993).

(note: since this list was prepared, the publication ‘Peramangk Culture and Rock Art in the Mt Lofty Ranges of SA’ by Robin Coles has become available).

As yet, no major work has been been produced concerning the Peramangk Aborigines of the Adelaide Hills.

Below is a select list of references, where scattered information appears.

-

ADAMS, John W. My early days in the colony . Published privately, Adelaide 1902.

-

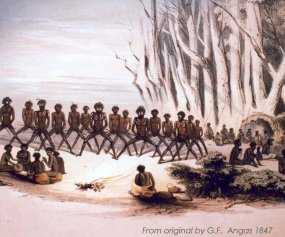

ANGAS, GF. Savage life and scenes in Australia and New Zealand (Vol I). Smith, Elder & Co, London 1847.

-

BISHOP, GC. Stringybarks to orchards: a history of Forest Range and Lenswood. Investigator Press, Adelaide 1984.

-

BRAUER, A. A few pages from the lives of the Fathers. From The Australian Lutheran Almanac Adelaide 1928.

-

BROWN, L (Ed) et al. A book of South Australia - women in the first hundred years . Rigby, Adelaide 1936.

-

BUCHHORN, M (Ed). Emigrants to Hahndorf: a remarkable voyage. LPH, Adelaide 1989.

-

BULL, JW. Early experiences of life in South Australia, and an Extended Colonial History. ES Wigg & Co, Adelaide 1884.

-

BULL, JW Early experiences of life in South Australia, edited, with annotations, by BUTLER, Reg. Peterson Press, Hahndorf 1993.

-

BUTLER, Reg. The quiet waters by - the Mount Pleasant District 1843-1993 . Gillingham, Adelaide 1993.

-

CAMPBELL, TD. Notes on the Aborigines of the South-East of South Australia. From Transactions of the Royal Society of South Australia, Part I. No 58: 22-32.

-

CAMPBELL, TD. Notes on the Aborigines of the South-East of South Australia. From Transactions of the Royal Society of South Australia, Part II. No 63(1): pp 27-35.

-

CAWTHORNE, WA. Diaries and notes 1844-1846. Mitchell Library, Sydney. (Some papers also held in SA State Records, 55 King William Rd, North Adelaide 5000)

-

COLES, R & DRAPER, N. Aboriginal history and recently-discovered art in the Mount Lofty Ranges. From Torrens Valley Historical Journal, No 33: pp 2-42. Torrens Valley Historical Society, Gumeracha 1988.

-

DYSTER, T. Pump in the roadway and early days in the Adelaide Hills. Investigator Press, Adelaide 1981.

-

FINLAYSON, W. Reminiscences . From Proceeedings of the Royal Geographical Society (SA Branch) 1902. Adelaide 1903.

-

FOSTER, R (Ed) Sketch of the Aborigines of South Australia - references in the Cawthorne Papers. Aboriginal Heritage Branch, SA Department of Environment & Planning, Adelaide 1991.

-

GARA, T & TURNER, J. Two Aboriginal engraving sites in the Mount Lofty Ranges. From Journal of the Anthropological Society of South Australia Inc. No 24 (2).

-

HART, AM. Early culture contact in South Australia. From The Aborigines of South Australia: Their background and future prospects. University of Adelaide, Department of Adult Education, Adelaide 1969.

-

HOSSFELD, PS. The Aborigines of South Australia: Native occupation of the Eden Valley and Angaston Districts. From Transactions of the Royal Society of South Australia, No 50: pp 287-297.

-

KING, F. Concept plan, Arbury Park Earthwatch reserve, Southern Mount Lofty ranges, South Australia. Wildlife and Park Management Field Study. SA College of Advanced Education, Salisbury 1987.

-

MEYER, A The Encounter Bay Tribe. From The native tribes of SA, edited by Woods, JD, pp 185-206. ES Wigg & Son, Adelaide 1879.

-

MOUNTFORD, CP. Aboriginal cave paintings in South Australia. From Records of the South Australian Museum, No 13 (1): pp 101-5 Adelaide 1957.

-

MOUNTFORD, CP. Cave paintings in the Mount Lofty Ranges. From Records of the South Australian Museum, No 13(4): pp 467-70.

-

MUNCHENBERG, RS et al The Barossa - a vision realised . LPH, Adelaide 1992.

-

NEWLAND, S. Memoirs . FW Preece, Adelaide 1926.

-

PREISS, KA. Aboriginal rock paintings in the Lower Mount Lofty Ranges, four new sites described. From South Australian Naturalist, No 39 (1): pp 5-12.

-

PROEVE, HFW. A dwelling-place at Bethany. LPH, Adelaide 1983.

-

REYNOLDS, H. The other side of the frontier. Aboriginal resistance to the European invasion of Australia. Pelican, Ringwood Vic 1982.

-

SANDERS, J. Reminiscences. Manuscript 1909, Mortlock Library of South Australiana.

-

SCHMIDT, R. Mountain upon the plain. A history of Mount Barker and its surroundings. Gillingham, Adelaide 1983.

-

SCHÜRMANN, EA I’d rather dig potatoes: Clamor Schürmann and the Aborigines of South Australia . LPH, Adelaide 1987.

-

STIRLING, EC. Aboriginal rock paintings on the South Para, Barossa Ranges. From Transactions of the Royal Society of South Australia, No 26: pp 208-11, Adelaide 1902.

-

STIRLING, EC Preliminary report on the discovery of Native remains at Swanport, River Murray: with an inquiry into alleged occurrence of a pandemic among the Australian Aboriginals. From Transactions of the Royal Society of South Australia No 35: pp 4-46, Adelaide 1911.

-

TAPLIN, G. The Narrinyeri. From The Native Tribes of South Australia, edited by Woods, JD, pp1-134 ES Wigg & Son, Adelaide 1879.

-

TAPLIN, G The folklore, manners and languages of South Australain Aborigines. SA Government Printer, Adelaide 1879.

-

TEUSNER, RE. Aboriginal cave paintings on the River Marne near Eden Valley, South Australia. From Mankind No 6 (1): pp 15-19 1963.

-

TEICHELMANN, CG. Illustrative and explanatory notes of the manners, customs, habits, and superstitions of the Natives of South Australia. Adelaide 1841.

-

TINDALE, NB Aboriginal tribes of Australia. University of California, Berkeley USA 1974.

-

TINDALE, NB & SHEARD, HC. Aboriginal rock paintings, South Para River, South Australia. From Transactions of the Royal Society of South Australia No 41. Adelaide 1927.

-

TOLMER, A. Reminiscences of an adventurous and chequered career at home and at the Antipodes , Vol 1. Sampson, Low London 1882.

-

WOODS, JD (Ed). The Native Tribes of South Australia. ES Wigg & Son, Adelaide 1879.

-

WYATT, JP. The Adelaide Tribe. From The Native Tribes of South Australia, edited by Woods, JP, pp 157-181. ES Wigg & Son, Adelaide 1879.

Additional Material

Buchhorn, M (Ed) Emigrants to Hahndorf - a remarkable voyage Adelaide 1989.

The savages there (in SA) are a race of humans of extremely ugly physical appearance. They go about like cattle, as naked as they came into the world. Only a few of them have a kangaroo hide slung around them to hide their nakedness. Smallpox must be common among them, as the majority of them bear its scars. Their hair is still and so long that it hangs down to their shoulders. They have a liking for smearing fat into their hair and dyeing it red. In fact, they do this to the whole head, using the powder produced by rubbing two stones together. This plasters the hair so that it dangles in thick clumps around their necks. The facial features are without exception very ugly. The upper part of the body is thick and clumsy, but they have quite thin loins and legs.

They have divided themselves into small tribes (as the English call them), perhaps fifty to sixty men in each company. Each tribe has its own king. They are almost always at war with each other, generally fighting about their women. There are many more male than female natives. People think that they kill and eat the children of the female sex at birth. A man who is looking for a wife will wear a white cockatoo feather in his hair, which means that his desire can be seen even from the distance. Each has a hole in the lower part of the nose between the nostrils, and they stick a six-inch long thin reed through this when they are in mourning.

In spite of their being sluggish and lazy, each group still has its own burial ground to which they take their dead, sometimes a distance of some miles. They make a proper grave which they even line with kangaroo skins, and they adorn the tops of these graves with tree bark. The German missionaries there told me that they have witnessed such a funeral procession. The dead man is laid on six sticks and covered with a kangaroo skin, and at each end of the sticks there is a man who acts as bearer. Every forty to fifty paces they stopped: each time a person charged with this particular duty went to the corpse, raised the kangaroo skin, and carefully inspected whether the dead man had not perhaps come back to life.

Their laziness extends so far that they do not even build themselves any sort of hut to protect themselves from the wind and rain. Generally, sixteen to twenty of them gather near sunset, tear some branches from the trees, and lay these in a circle around the company. Then they start a fire in the middle and sleep lying around it. On the following morning, each goes his way.

In spite of their brutish existence, they show a tendency to vanity; if someone gets hold of a piece of European clothing, he looks proudly at his colleagues, but as none of them has a complete suit of clothes, and they just use what they have, they often appear in absurd outfits. The most comical one that I saw was a man who was completely naked apart from a blue frock coat with bright buttons. It was astonishing to see this coat on the naked body. They are very fond of things which are brightly coloured and shiny, such as pieces of coloured glass or bright metal. If they manage to get something of this kind, they tie it to a thread and hang it around their necks. When Captain Blenkinsop’s boat suffered a misfortune at the mouth of the Murray last year, his sextant was washed ashore. The savages found it and straight away broke the expensive instrument into small pieces, so that each of the participants could have a piece of it to hang around his neck as adornment.

For all that they are savages, they each have a name of their own. However, they seem to prefer the European names to their original ones and now all use names of the English kind, as for example, Jack, Tom, Jim, Pat etc. They also have an approximate idea of their age, though only in months. Each carries a stick in which he makes an incision with a sharp stone at every new moon. He is as many months old as there are incisions in the stick. However, I doubt whether these people have so much sense that parents make this sign for their children before they are able to do so for themselves. It is very likely that the number of notches is a record of their age from about four or five on, although perhaps earlier, for their children are soon able to fend for themselves. I was amazed at the little black people, who could scarcely have been a year old to judge by their size, already running about among the old ones and playing games as children do. It is certainly not physical strength which gives them this advantage over the Europeans, indeed even over negroes in general. I ascribe it to their natural hardiness, as their body build is, as I have already said, only slight. A man whose word can be trusted told me that one morning at ten he had found a woman lying in childbirth under a tree five English miles from the town, and that at three in the afternoon he had seen the same woman in the town with her child on her back.

The female sex seems to me more advanced in the kind of knowledge they have been able to acquire than the men, who know only how to use their spears. I saw a jacket there, made solely of small opossum skins, which a female savage had made, and it was so beautifully sewn that few European women could have done the work better. If one considers the tools with which this work was done, then it is clear that it deserves even greater admiration. A thread had been made from the gut of a kangaroo. A small bone, pointed at one end, served as the needle; it has apparently not occurred to them to make a hole or eye in the blunt end, because first a hole was made with the needle, and after that the thread was drawn through separately.

Each savage, whether male or female, wears over one shoulder a net skilfully made from kangaroo gut, in which they store the spoils of their hunting. The men always have their instruments of war fastened across the net as well. These consist of a spear, that is, a long stick, one end of which resembles an arrow. Since Europeans arrived, they fix bits of glass (previously, pieces of flint) to the pointed end, and gum sharp pieces on both sides as well. There is also a small stick about three feet long, with a kangaroo tooth fastened on one side of the tip, forming a barbed hook. They fix this tooth to the upper end of the spear, and are very adept at shooting with it for a distance of 60 ells. In addition to these weapons, they have a small cudgel of very hard wood, about two feet long, with a knob at one end, which they call wirra in their language. When the spear has been thrown, then this cudgel serves as a weapon of war. They use a fourth stick, which has been smoothed down at one end, as a spade for digging roots out of the ground; it also serves as a calendar record of their age, as mentioned earlier.

I have myself seen how they instructed their children or conducted exercises with them in the use of these weapons. They had set up a round wooden disc as big as a plate, at which they then took aim. Each child was lined up with his spear, then one of the old men placed himself at a distance of about twenty paces from them and rolled the disc along diagonally in front of the children. I saw them hit the disc several times when it was moving at its fastest.

In the company of one of the missionaries I was once present when a whole crowd of these savages had gathered. A spear had been stood up against a tree in the sun, and I took it up in my hand so that I could inspect it. One of those present gave a terrible cry and sprang at me, tore the spear out of my hand, and stared at me malevolently. My companion intervened and indicated to this savage that I had only wanted to inspect the instrument, and then he immediately calmed down. He pointed to his spear, which was still new and had been propped up at the tree for the gum to dry. I pointed at the spear and then at my arm, to indicate to him that he could injure the arm with it. This made him and his comrades laugh heartily; he shook his head and came towards me, first pointing to his spear and then to his heart, and nodded at me, as if to make me realise that it would have been a better place to aim at.

These people seem to be very good-natured, at least those of them who live in the region of the Onkaparinga River. The general opinion is that they are less good-natured on the other side of the Murray. If they are not provoked, they do no one any harm. The few cases where the savages have committed murder since the English settled here, are rather to be ascribed to ignorance or folly than to viciousness. The story of Captain Barker’s murder two years before was certainly an outrage, but it was clearly not caused by bloodlust. Captain Barker was on the south side of the Murray and wanted to make a sketch of Granite Island in Encounter Bay; he was prevented from doing so from this side of the Murray by the hills jutting out from the Australian side. So he decided to swim across the river, and make his observations from the opposite side. He left his Register 6/5/1843 3acompanions behind, as they were not good swimmers, tied his compass to his head, reached the other shore and completed the work as planned. However, when he wanted to go back, a crowd of savages gathered around him, gazing in amazement at his compass. After Barker had fastened this to his head once more and had stepped into the river, it apparently occurred to the savages that they should take possession of this shiny object, and so they speared Barker. If he had been willing simply to hand over his compass to these savages, they would not have murdered him.

The former king of the savages on the Onkaparinga, usually called King John, has been appointed to a post in the police force by Governor Gawler and is doing an excellent job here in Adelaide. If the savages have stolen something or have committed some other misdemeanour, the Governor just gives John a hint and he finds the miscreant - he does not return to the town until he can bring the criminal along with him.

It is almost inconceivable that these people used to live solely on kangaroo meat, as the country has never been particularly well supplied with these animals. Of course, it is true that the kangaroo retreats whenever the white man arrives anywhere. But if they were so common, then some of these animals would have been encountered on the overland journeys between Adelaide and Sydney that have already been undertaken by several Europeans. It is possible that the kangaroos have moved away right up into the interior, which has not yet been explored. The great number of skins they still own is evidence that they have hunted down many of these animals. Anyway, there are very few now in the surrounding district. It is therefore more likely that the people eat the fish which abound in the rivers. One also finds that the various tribes always stay near a river, and many mussel shells have been found on the banks of the Murray, although no mussels have actually been seen. Therefore people surmise that the savages get the mussels by diving down to the bottom of the river.

They also have their own method of fishing. They make themselves a dam in the river, high enough to let about a foot of water flow over it. When the fish get near the dam they have to come up close to the surface of the water, and the savages are standing there, ready to spear them.

Their kangaroo hunts are also of a simple kind. If they notice one of these animals, ten or twelve men gather in a circle around the prey, and in this formation they gradually close in on it, until they are so close to the kangaroo that they can hit it with their spears. Similarly, when the savages catch the opossums that are always to be found in hollow trees, they usually hunt in pairs. One of them climbs up the tree and waits at the hole that the animal uses as an entrance, the second man lights a fire at the bottom of the tree, and then the smoke drives the animal out of its hole and they catch it.

There is another strange and shameful kind of hunt which takes place in summer, when the grass in the hills has become dry as straw. But this involves a whole tribe. They form a circle about twenty English miles in diameter, light fires around this area, and then direct the fire closer and closer in toward the centre of the circle. The long dry grass, bushes and young trees burn fiercely; all the animals living in this area flee toward the centre, where the savages then catch them. A hunt like this occurred during our stay, and the fire burned for some days; I had never before seen such a fire. It is desirable that this practice be abolished. Of course, they light quite large fires in the hills at every new moon, which has led people to conclude that they worship and pray to the moon; but this latter practice is hardly to be compared with the former one.

A number of people are now surely wondering how the savages light the fires. However, they have a simple, easy way of doing this. There are many thin sticks about two to three feet long, growing in the long grass - the English call them grass-wood. They break one of these sticks in two, put the pointed end against the blunt one, and then rub the two pieces so skilfully between their hands that the stick is burning briskly within two minutes at the most.

There are still various things remaining to be said about the conditions reigning among these savages, but I will omit them in order to avoid going into too much tedious detail. And so I will now close with the comment that the present generation of this race of people will, in my opinion, surely never be able to be trained to be useful beings in the world.

From the Reminiscences of Pastor William Finlayson.

But at the distance inland of twelve or fifteen miles a grand range of hills rose before us, white and glistening with the long dry grass of summer, and well wooded. Before next day’s sunrise a great change took place in the landscape before us. The watchers on deck beheld a fire on one of the hills, which seemed to spread from hill to hill with amazing speed. All on board were now awake and on deck looking at this grand conflagration, as it seemed as if the whole land was a mass of flame. In the morning, a great change had taken place; the whole range was as black as midnight, except where the trees were burning, and shortly after we landed the mystery was explained. At the end of summer as this was, the natives had set fire to the long dry grass to enable them more easily to obtain the animals and vermin on which a great part of their living depends...

The natives were then in considerable numbers, and there were frequent alarms. On one night, the whole colony was awake and under arms, but we found there was not the least cause for alarm. Our great fear arose from what we supposed were the tribes beyond the hills, but we soon found out that there were fewer there than among the settlers. Once they held a great corroboree, as it was called, and it did seem like a dance of devils. The poor creatures often came into and even slept in our hut, but never did they in any way molest us.

They destroyed some at least of their own female infants, for one Sabbath morning I came upon a large camp near to West-terrace, where I found a number well known to me, some of them wild, ferocious-looking fellows - Rodney, Captain Jack, and others. They were talking together very earnestly, and there was an unusual bustle and excitement among them. I was soon made aware that a new female infant was in one of wurlies. I made signs requesting to know what they were going to do with it, as the mother seemed not have touched it. Rodney took up a waddy, and by a very significant motion signified that they were about to kill it by a blow on the head. Making signs for them to wait, I went for and returned with all speed, bringing my wife with me, who tried to get the mother to take it up, but could not persuade her to touch it. I then went for the Protector, as he was called, and he, with the interpreter and black woman who lived with him, returned with me to the camp. For a long time, all our arguments were unavailing. The mother was still suckling a boy two or three years old, and said he would starve if she took this one. We continued with them nearly the whole day, and after long palaver a treaty was agreed upon, by which the child’s life was spared. The mother continued to visit us, but about two years after the child died. Long ago, every one of the Adelaide and other neighbouring tribes died out. Certainly they were by no means badly used; on the contrary, they were kindly treated. No natives are now seen in Adelaide except those that come from a considerable distance ...

We often looked to the Mount Lofty Range of hills, and wondered what was the condition of the natives beyond them, feeling assured that there was more hope for instructing those who were away from the bad influence of white men. No one had as yet been beyond the hills to give information as to what was to be seen there, and I resolved to go and see.

Old Colonist - Fifty-one years ago - Mt Barker Courier 8 December 1899

Of course, there were plenty of Aborigines here then - about 300 of them, known as the Mt Barker tribe. They were very peaceable, but rather light-fingered, although they could easily be induced to work for the whites, who treated them very well. The camp was located on the Flat, and the blacks did not altogether see the force of being intruded upon by the white people, although they did not openly resent a visitation. Some of the men were fine, big fellows, and old man Robert the chief, was a splendid specimen.

I remember a war between the Mt Barker and Wellington tribes over one of our blacks eloping with a Lakeside girl. The Wellingtonians came up after their dark angel, and several days previous to their arrival, the local Aborigines scented their approach. The battle was fought on cro’s nest hill, and spears, boomerangs, waddies and bark shields were very plentiful. Just as things were getting exciting, a woman came for the police - we had two, Corporal Hall and Trooper Goy. So enraged was the husband that as she ran, he threw a spear at her, after which he seized the pointed end and pulled the weapon clean through her body. I believe she died from the effects.

One of the warriors who was particularly active got speared in the side, the point breaking off in his flesh, and the manner in which the lubras used to place one foot each side of the wound and jump and down to cause the piece to work out was something awful to think of, especially when one imagines he can hear the groans of agony from the victim. The police restored order between the tribes, and the young woman was allowed to return to her people. All the while she was here, she howled piteously.

The natives tipped their spears with the teeth of animals or bones. In the winter, they used to go to the Lakes, being allowed by the other tribes to occupy certain parts for fishing and fowling. One practice of the blacks will be interesting. In producing fire - for we had no lucifer matches in those days, but the flint and steel - they used to rub two dry reeds together. The first made a hole in the side of one of them, putting some dry sand in it, and the friction caused by rubbing the other reed in the hole soon produced the desired result.

RWM Waddy, Deputy Postmaster General - The old days at Mt Barker, The Chronicle 18 Jan 1913.

Yes, Mt Barker was a paradise and the scene of many a war. The blackfellows will understand the relation of the terms, maybe, better than their paler conquerors. They were fond of fighting in those days, and next morning after a conflict, I have seen my father with his hand cutting away the matted hair and putting sticking plaster over the woundds. No doubt, he said with a smile, he sent the bill to the Government afterwards. The blacks used to get very drunk at times. They visited the shops and procured sugee bags that the brown sugar came from Mauritius in. The sugar generally soaked through the bags as treacle, and the Aboriginals used to leave the bags in water for a few days until the treacle fermented. That stuff made them as drunk as good old English rum. I have never seen anyone killed. Their heads were too hard. They hammered one another about right willingly, though.

Father, the late Edward Waddy, first doctor at the Kapunda Mines. Later at Kooringa and then at Mt Barker and Strathalbyn.

Mrs Lucy Coleman’s reminiscences Mt Barker pioneers. The Chronicle 24 Nov 1924.