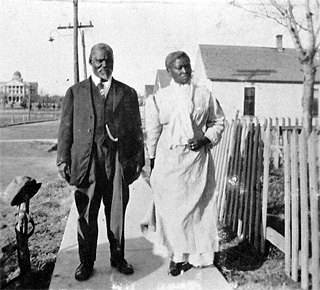

Joe and Alice Skinner in Quakertown, c. 1913

Joe and Alice Skinner in Quakertown, c. 1913

Quakertown was an African-American settlement in Denton, from the 1880s to the 1920s, a town-within-a-township built upon Booker T. Washington's philosophy of self-reliance and black entrepreneurship.

The residents were removed by the Denton government to make room for Civic Center Park (now Quakertown Park). Quakertown was originally a settlement of African-Americans in Denton, named after the Quakers who had helped in the Underground Railroad. When Texas Woman's University was built in close proximity, there was an election over whether or not to build a park in the location of Quakertown. The election was won in favor of the park, and the African-American residents were forced to leave.

History

Beginning

The 1920s were a dark time in history for black people in the American south, and Denton was no exception. The racism and segregation of black communities in southern cities and towns was demonstrated in the forced eviction of the residents in the thriving Denton community called Quakertown.

At the Emily Fowler Public Library, on the very land where Quakertown once stood, a comprehensive collection of Quakertown’s history is kept. Records from the 1920s and before have been reproduced and consolidated into a unique file showing the history of this tragedy as reported by the area newspapers, early publications and official town documents.

The people of Quakertown were the sons and daughters of freed slaves who settled in an area they called “Freedman Town” in 1875. Freedman Town was located in the south east side of the modern day city of Denton. These settlers consisted of newly freed slaves who purchased land in Freedman Town and started raising families. As the population grew, the next generation began to spread northward, eventually forming Quakertown, an all black neighborhood named for the Pennsylvania Quakers abolitionists that helped their parents a generation before. By the early 1900s, Quakertown extended from the recently established College of Industrial Arts (CIA), known today as Texas Woman's University, south to McKinney Street and from Bell Avenue to Oakland Avenue in the center of Denton.

The neighborhood was a thriving community of black families, business, churches, and a school. By 1913, Quakertown would boast more than 60 families. The community was self-sufficient with its own doctor, grocery store, and social clubs including the Masons and The Odd Fellows. Though the school burned down under mysterious circumstances in 1913, by 1915 it had been rebuilt and was once again attracting black students. The community supported three churches; Pleasant Grove Missionary Baptist church, St. Emmanuel Missionary Baptist church and St. James African Methodist church. Businesses in the neighborhood included a drug store, a boarding house, and several retail stores. These qualities, along with city services that came with being in such close proximity to the town’s center, would make the community attractive to other black families in the surrounding areas.

Eviction

As Quakertown grew, its northern neighbor would launch a campaign to shut it down. By 1920, CIA had grown to become a successful, regional woman’s finishing school, and was petitioning the state to become a full-fledged liberal arts college. The petition was denied, CIA president Dr. F.M. Bradley believed, because of the black neighborhood on its southern border. On November 18, a notice was published in the Denton Record Chronicle newspaper expressing “…concern for the sanctity of the homes and purity of the young girls…who are without immediate parental guidance…” Two days later in a speech to the Denton Rotarians Dr. Bradley states, “[Denton] could rid the college of the menace of the negro quarters in close proximity to the college and thereby remove the danger that is always present…”

A series of presumptive and racially inspired notices and editorials followed, as well as erroneous reports of crime, disease and lack of sanitation in the Quakertown community. The newspaper wrote “every thinking negro who lives in that district would like to get away.” and called for “[A] vote for the good of the order.”

In December 1920, Denton resident J. L. Cooper brought a petition before the Denton City Commission calling for a bond vote to purchase Quakertown and turn it into a city park. The commission approved the petition and in a citywide vote on April 5 of 1921, a $75,000 bond was passed. Quakertown families were given the option of selling their property to the town or having their house moved to a pasture owned by local rancher, Albert Miles, adjacent to the old Freedman town.

Those that chose to sell found out quickly that the pasture (by then named Solomon Hill) was the only area of Denton that the white population would allow them to move to. Notices went up in the white neighborhoods surround CIA warning black residents from moving into them. One such notice, posted in the neighborhood east of CIA stated, “Negros take notice - No building, no moving north of the R.R. or east of CIA or south of Jase Walker’s. Those already there will be given time to sell there (sic) property and move. Understand?” (Dallas Morning News, 7/1/22)

The black residents were not offered much compensation or time to leave their properties. Those that refused to sell or tried to negotiate better terms found their houses condemned by the town and were forcefully evicted. Only one Quakertown resident, Will Hill, filed suit against the town, but quickly dropped his lawsuit when faced with intimidation and threats by the Ku Klux Klan.

By 1923, all of the residents of Quakertown were gone. According to historians at the African American museum in Denton, two thirds of the former Quakertown residents moved completely out of the area, including the only black doctor in Denton County, Dr. E. D. Moten, whose history is well documented in the museum. Most of the families that remained had been relocated to Solomon Hill. The town razed all remaining structures, with the exception of a single home owned by the only white resident of Quakertown. All traces of the once thriving black community were gone.

The city called the new public space "Civic Center Park" until 2007 when it was renamed "Quakertown Park" in honor of the former community.

Depictions in pop culture

White Lilacs, a novel written by Carolyn Meyer, depicts the removal and struggle of the residents of Quakertown, though all character names and other specifics have been changed. Armadillo Ale Works also just released their first public beer offering on 3/1/13 and dubbed it Quakertown Stout.