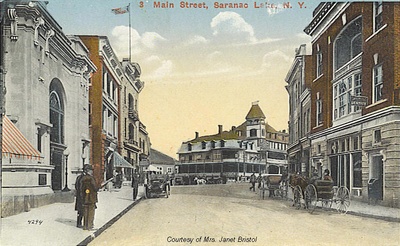

Main Street looking north, 1908

Main Street looking north, 1908

The Berkeley Square Historic District is located in the center of Saranac Lake, and is made up of the 1926-28 Harrietstown Town Hall and twenty-two contributing commercial buildings constructed between 1867 and 1932.

If the Lake Flower Dam, where Captain Pliny Miller built his sawmill in 1827, is the root of the Village of Saranac Lake, then the place where the road from Baker's to Blood's (Main Street) is joined by the road to West Harrietstown (Broadway) is its heart. At that intersection, Charles Gray built his Berkeley House in 1875; and, though it is actually a "Y", this parting of the ways came to be called Berkeley Square.

With the sawmill and the hotel (there were also two more small hotels or inns by the dam), the village had both of the basic ingredients upon which the economies of most Adirondack communities have been and are based: lumbering and tourism. But, in this particular community, something else was in the works.

A man named Trudeau was discovering a way to cure tuberculosis. The vehicles of this cure were not exotic molds or synthesized organic compounds (as they eventually did become) but rest, good food, clean environment, peace of mind. It was medicine for the whole person. It had to be taken for a long time, and it meant staying in one place. The time was often the span of a human life. The place was this village, Saranac Lake.

Main Street looking north, 1900 The Berkeley Square Historic District today encompasses twenty-four buildings on Main Street, nine on Broadway, and, if the Berkeley Barn is counted, one on Woodruff Street. When the first two patients went into Dr. E. L. Trudeau's "Little Red" cottage in 1884, probably no more than four of those structures were standing. There was, in addition to them, the Berkeley House itself, a scattering of frame houses, and much open space.

Main Street looking north, 1900 The Berkeley Square Historic District today encompasses twenty-four buildings on Main Street, nine on Broadway, and, if the Berkeley Barn is counted, one on Woodruff Street. When the first two patients went into Dr. E. L. Trudeau's "Little Red" cottage in 1884, probably no more than four of those structures were standing. There was, in addition to them, the Berkeley House itself, a scattering of frame houses, and much open space.

Perhaps three more buildings went up in the District before 1890. By that year, the successes at Adirondack Cottage Sanatorium on Mt. Pisgah just north of the village had begun to be acknowledged worldwide. For the next six decades, thousands and thousands of tuberculosis sufferers would come to Saranac Lake seeking a return to health. Furthermore, at least for the first three of those decades, Saranac Lake was one of the few places in the world where a tubercular person could expect to be accepted and respected as a fellow human rather than shut away and shunned as a pariah.

One aspect of the response to the demand created by "The Cure" was a frenzy of building. By 1910, all but five of the District's buildings had been erected. It has been estimated that fully 700 of the village's 2200 buildings went up in the space of twenty years. Most of those would house patients.

Broadway at Main St. looking south - 1901 Housing was an obvious need created by the patients but by no means the only one. The patients would require goods and services; and, since most of the patients could not get around, there was a special emphasis on goods with service. Just about every merchant would deliver just about anything they sold to just about anyplace. And, if they wouldn't, there was a profusion of independent delivery people who would. Of course, the people who came to provide the goods and services and the people they hired needed goods and services and homes as well, and so the town grew. And it developed an economic base quite different from its neighbors.

Broadway at Main St. looking south - 1901 Housing was an obvious need created by the patients but by no means the only one. The patients would require goods and services; and, since most of the patients could not get around, there was a special emphasis on goods with service. Just about every merchant would deliver just about anything they sold to just about anyplace. And, if they wouldn't, there was a profusion of independent delivery people who would. Of course, the people who came to provide the goods and services and the people they hired needed goods and services and homes as well, and so the town grew. And it developed an economic base quite different from its neighbors.

Because of the mushrooming of the curing industry and the additional influence of the many nearby "great camps" (whose golden age — 1890-1930 — coincided with Saranac Lake's period of most rapid development), the village became neither a lumbering and wood-products center like Tupper Lake to the west nor a tourist mecca like Lake Placid to the east. Instead, it became the nation's Pioneer Health Resort and the commercial hub of the entire region.

In 1920, according to Donaldson's A History of the Adirondacks, Saranac Lake had, aside from hundreds of private residences, "145 buildings in which housekeeping suites are rented, one large modern apartment house, 85 boarding houses, 13 hotels, 30 or 40 liveries renting cars, 75 stores, a telephone exchange, a union station (served by the Delaware and Hudson and the New York Central), three schools, a public library, two hospitals, two national banks, a boys-club house, (and a curling club rink), four churches, and two theaters." [The parenthetical information is this writer's addition]

Main Street looking north, 1910 Concerning those 75 stores, among them were: at least nine pharmacies, at least ten clothiers, and at least a dozen grocers; also two and sometimes three furriers, numerous tailors, and a full-sized department store as well as jewelers, bookstores, art supply stores, tobacconists (at least two), photo and gift shops and just about every other kind of shop imaginable. Mixed in among all these were more than enough lawyers, real estate dealers, and insurance men and at least two stock brokerage offices and a thrice-weekly newspaper. But, of course, no attempt at a list can convey the variety or vitality present in the stores and along the streets.

Main Street looking north, 1910 Concerning those 75 stores, among them were: at least nine pharmacies, at least ten clothiers, and at least a dozen grocers; also two and sometimes three furriers, numerous tailors, and a full-sized department store as well as jewelers, bookstores, art supply stores, tobacconists (at least two), photo and gift shops and just about every other kind of shop imaginable. Mixed in among all these were more than enough lawyers, real estate dealers, and insurance men and at least two stock brokerage offices and a thrice-weekly newspaper. But, of course, no attempt at a list can convey the variety or vitality present in the stores and along the streets.

All this was in a community of not quite 7,000 people which, though it continued to grow for another decade and a half, never topped 10,000. Finally, it was incredibly concentrated. A brisk walk could take a person the length of the business district in less than ten minutes.

The richness and intensity of Saranac Lake's mercantile scene made the place far more urban in character than many a much larger town. The common bond of the search for health made for an uncommon mix of peoples and a bracingly cosmopolitan atmosphere. The village was a miniature melting-pot. Farm boys and factory workers, bankers and baronesses, Americans and Cubans and Norwegians and Filipinos and so many others of every social and cultural origin were here because of a very special need. That need was reflected in the depth and diversity of Saranac Lake's business district and even in the facades of many of its commercial buildings with their upper-story verandas and recessed balconies and galleries to allow apartment-dweller/patients to take the air.

Finally and most importantly, there is the effect that those special people with their special need had upon the business district and upon the community as a whole when they themselves stood behind the counter or sat behind the desk.

As Donaldson wrote in 1920: "Out of the many that came (to Saranac Lake) each year in search of health, a few (actually quite a few)... often saw the wisdom of perpetuating the conditions that led to their improvement instead of returning to the environment of their breakdown. Some could remain without worry over income; others were less fortunate, or disinclined to be idle. They engaged in some new or familiar business, and in thus serving themselves they served perforce the community of which they became a part."

Donaldson knew this well. He was speaking from personal experience. It was an experience shared by many others who in numberless ways famous or forgotten contributed to Saranac Lake's growth and prosperity. It was an experience that engendered an attitude that was and is the foundation of those contributions. This attitude was expressed perfectly by the late, local humanitarian, Tony Anderson: "I owe my life to this place. How do I repay a debt like that?"

Following the collapse of the curing industry after WWI, Saranac Lake steadily lost residents (current population is about 5000) and the core of its commercial section lost some twenty buildings. The innermost and still most representative portion of that core is encompassed by the Berkeley Square Historic District.

Original text by Philip L. Gallos

| Building, dates | Old Address | Post 911-system Address | Notes |

Harrietstown Town Hall, 1928 Harrietstown Town Hall, 1928 |

30 Main St. | 39 Main St. | A Scopes and Feustmann-designed, two-story, flat roofed, steel frame, brick and limestone Beaux-Arts-style public building with a prominent bell and clock tower. It contains offices, meeting rooms and a large auditorium. It was built on the site of the previous Town Hall, that burned in 1926. |

Walton and Tousley Hardware, c. 1900; addition c.1915 ; alteration c.1960 Walton and Tousley Hardware, c. 1900; addition c.1915 ; alteration c.1960 |

34 Main St. | 43 Main St. | Non-contributing. Home of the Rice Furniture Store since 1948. |

Tousley Storage Building, 1924 Tousley Storage Building, 1924 |

38-40 Main St. | 49 Main St. | Originally built as a parking garage and automobile dealership, it was used for many years for microfilm record storage for many of the nation's major companies. |

Milo Miller Store, 1867 Milo Miller Store, 1867 |

42-44 Main St. | 51 Main St. | Built by Milo Miller in 1867, it is the oldest commercial structure in the village. Until 1890 it was the home of Miller's Store |

The Book Store, 1925 The Book Store, 1925 |

46 Main St. | 55 Main St. | Art Deco, design by William G. Distin |

Little Joe's, Between 1879 and 1894(?); brick facade c. 1922-23 Little Joe's, Between 1879 and 1894(?); brick facade c. 1922-23 |

48-50 Main St. | 57 Main St. | Built by Milo Miller, the newest and largest of his Second Empire buildings, built about 1890. Joseph Gladd, a flyweight Golden Gloves champion known to all as "Little Joe", that became the most popular Saranac Lake meeting and drinking place of the 1950s and early 1960s. |

Post Office Pharmacy, Post Office Pharmacy, before 1879; facade c.1921 |

52 Main St. | 61 Main St. | Built by Milo Miller, it was originally used as a grocery and meat market. Since 1936, it has been the Post Office Pharmacy. |

Donaldson Block, 1901; Donaldson Block, 1901;balconies enclosed in 1930s |

56 Main St. | 63 Main St. | Built by Alfred L. Donaldson, it was home to photographers George Baldwin and William L. Distin, and Distin's son, William G. Distin, Sr. |

Haase Block, Haase Block, 1907; rehabilitation 1985-86 |

60 Main St. | 67 Main St. | Designed architects Scopes and Feustmann, who were among the first tenants, it was also the home of the Saranac Lake National Bank. |

Telephone Exchange, 1909; alterations c.1964; rehabilitation 1982 Telephone Exchange, 1909; alterations c.1964; rehabilitation 1982 |

68 Main St. | 69 Main St. | The building served as the telephone exchange building under several owners for over fifty years. It was also home to William F. Kollecker's first studio. |

Adirondack National Bank, Adirondack National Bank, 1906-07; heavily altered 1962 |

70 Main St. | 75 Main St. | Non contributing. A once handsome historic structure obliterated by the 1962 Marine Midland remodeling inside and out. |

Fowler Block; Old Enterprise Building, 1900; addition 1926 Fowler Block; Old Enterprise Building, 1900; addition 1926 |

76 Main St. | 77 Main St. | Home of the Adirondack Enterprise for forty-seven years. Designed by William H. Scopes. Rear extension designed by William G. Distin, Sr. |

Roberts Block; Finnigan Building, 1900 Roberts Block; Finnigan Building, 1900 |

78 Main St. | 79 Main St. | Home of T.F. Finnigan's Clothiers since 1923; the original cherry wood fixtures and furnishings are intact. |

Kendall Building, 1891; facade 1960 Kendall Building, 1891; facade 1960 |

82 Main St. | 81 Main St. | Originally Kendalls Pharmacy |

Mulflur Shoes, 1921 Mulflur Shoes, 1921 |

84 Main St. | 85 Main St. | Designed by Paul Jacquet |

Jack Block, 1910 Jack Block, 1910 |

2 Broadway | 1 Broadway | |

McIntyre Block, 1890 McIntyre Block, 1890 |

4-6 Broadway | 5 Broadway | |

Ayer Block, before 1891 Ayer Block, before 1891 |

10 Broadway | 7 Broadway | |

Altman's, 1932 Altman's, 1932 |

16 Broadway | 9 Broadway | Non-contributing |

Egler Block or Fair Store, c. 1912 Egler Block or Fair Store, c. 1912 |

18 Broadway | 11 Broadway | |

Scheefer Jewelers, Scheefer Jewelers, between 1897 and 1901 |

20-22 Broadway | 13 Broadway | |

Coulter Block, 1899-1901 Coulter Block, 1899-1901 |

71-79 Main St. | 76 Main St. | Designed and owned by William L. Coulter. In February, 1907, the offices of Coulter and Westhoff were located here. |

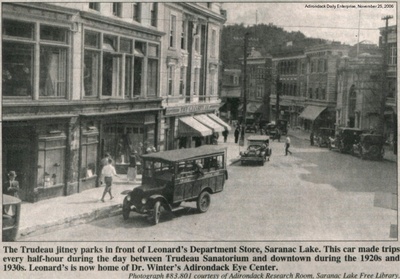

Leonard's Department Store, |

85 Main St. | 86 Main St. | |

Harding Block, 1895; 1904 six foot addition at right; 1910 store front. Harding Block, 1895; 1904 six foot addition at right; 1910 store front. |

89 Main St. | 90 Main St. | Intact 1918 Scopes and Feustmann oak storefront. |

Loomis Block or Downing Block, Loomis Block or Downing Block, 1896-99; 1908 |

15-17-19 Broadway | 14 Broadway | |

Ledger Block, 1895 and 1899; 1903 Ledger Block, 1895 and 1899; 1903 |

25 Broadway | 20-22 Broadway | |

Starks Hardware, Starks Hardware, 1898; alterations 1975 |

29 Broadway | 28 Broadway |

Berkeley Square Historic District

Berkeley Square Historic District

From the National Register of Historic Places Registration Form for the Berkeley Square Historic District:

The Berkeley Square Historic District is an outstanding, largely intact example of a late nineteenth century commercial streetscape in the north country region that clearly illustrates the development of Saranac Lake into a premier health resort of the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. The group of mixed-used commercial properties and the one public building that make up the, Berkeley Square Historic District constitute the heart of the original residential and business section of Saranac Lake, the largest village in the six-million acre Adirondack Park.

First settled in 1819, Saranac Lake remained a remote camp of guides and lumbermen until the arrival of Dr. Edward Livingston Trudeau in 1876 sparked its development as a sanitarium village organized almost entirely for the care of tuberculosis sufferers. The commercial center prospered and developed in the last quarter of the nineteenth century as a direct result of the emergence of Saranac Lake as a leader in the health care industry under the leadership of Trudeau. The period of significance of the Berkeley Square Historic District extends from 1867, when the first commercial building was erected in the district, to 1932 when the last of these buildings was constructed. The architecture of the district is characterized by three-story commercial buildings featuring retail space on the street level and rental apartments occupying the upper stories. The closely spaced, predominantly brick and stone buildings, embody vernacular adaptations of nationally popular architectural styles ranging from a Second Empire style store (c. 1867) to nine refined commercial buildings (built from 1900 to 1912) that reflect elements of the Classical and Colonial Revival styles. Several of these early twentieth century buildings were designed by the regionally prominent architectural firms of Scopes and Feustmann, William L. Coulter and William G. Distin,Sr. The construction of the Harrietstown Town Hall in 1928, with its Beaux-Arts inspired design, marked the peak of sophisticated architectural development in the Berkeley Square Historic District.

The commercial district continued to prosper throughout the early twentieth century, with the last architecturally distinctive commercial buildings constructed in 1932. The district is significant for its intensive sophisticated architectural development in this isolated community and is especially noteworthy for the adaptation of its commercial architecture to incorporate verandas and cure porches, features which had been introduced into regional architecture specifically for therapeutic reasons by Trudeau at his sanitarium. Cure porches became ubiquitous throughout Saranac Lake during its heyday as a treatment center, primarily in the residential areas. The introduction of these elements into the design of many of the stylish commercial buildings located in the Berkeley Square Historic District reflects the total involvement of the community in the single industry of tuberculosis treatment.

The first settlers in the area were the family of Jacob Smith Moody, who arrived in 1819. Captain Pliny Miller and family arrived in 1822 and by 1827 had built a dam to provide waterpower for a sawmill on the Saranac River, creating what is now Lake Flower. During the 1840s, Miller built the first hotel, just across the river from his sawmill. The third of the trio usually cited as founding families, that of Colonel Milote Baker, had established another hotel, a store and the first post office at the present intersection of Main and Pine Streets by 1854, where Baker served as the postmaster. By 1856, fifteen scattered families lived in the area that would become Saranac Lake, among them thirty-one students in two schools.

In 1865 Captain Miller's grandson, Milo Bushnell Miller, age 21, returned from action in the Civil War and established a trading post on Main Street. When the building burned in 1867, Miller built a fashionable French Second Empire building, still standing at 44 Main Street in the historic district, thus permanently establishing this section of Main Street as the retail business district for the village. Miller interpreted the style in locally available materials: wood shingles in place of slate, clapboard with corner boards in place of brick with quoins. Although the facade of this building has been somewhat altered by successive owners, the building retains substantial integrity of design and materials beneath this alteration.

The arrival of Dr. Edward Livingston Trudeau in 1876 with a case of tuberculosis marked the turning point in Saranac Lake's development. He had first lodged at Paul Smith's hotel, about ten miles north, a place he had loved when he came for hunting. Tuberculosis at that time was killing one person out of every seven, and a diagnosis of tuberculosis was virtually a death sentence. Trudeau's health improved in the mountain air, but he found himself unable to return to the city without a relapse. In 1876 he determined to find a place where he and his family could spend the winters:

We tried Bloomingdale, but no suitable house was to be had there, so we drove on to Saranac Lake... .At that time Saranac Lake village consisted of a saw-mill, a small hotel for guides and lumbermen, a school-house, and perhaps a dozen guides' houses scattered about over an area of an eighth of a mile. There was one little store kept by Milo B. Miller where flour, sugar, a few groceries, tobacco and patent medicines were sold and where the clerk was the telegraph operator. The two best houses were owned by "Lute" Evans, an old guide, where Mr. Edgar, Dr. Loomis's patient, boarded, and opposite was a fairly comfortable little clapboard house owned by Reuben Reynolds, also a guide. This was about the only house in the place at that tine large enough to take in my little family, and I managed to hire it for twenty-five dollars a month, unfurnished, for the winter.

What Dr. Trudeau described in his Autobiography as "Saranac Lake village" was most probably only the cluster of buildings that lay in Harrietstown, on Main Street in the Berkeley Square district. The houses referred to were replaced by commercial buildings in the early years of this century.

By 1876 Milo Miller had built a hotel called the Berkeley House, also in the Second Empire style. From then until the fire that destroyed it in 1981, the Berkeley was the center of Saranac Lake, and the "Y" intersection of Main Street and Broadway which it dominated has been known as Berkeley Square.

Gradually, as Trudeau felt better, he began to practice medicine. Dr. Alfred Loomis, whom Trudeau had met at Paul Smith's, began to send him a few selected patients. The relatively few health seekers who arrived in these years were housed just as those who came for the sporting recreation were in hotels, guides' cottages and boarding houses. As more patients took up residence, commercial activity increased on Main Street. In addition to the store at 44 Main and the Berkeley House, Miller built at least two other Second Empire style buildings, the first a single-story market at 52 Main Street built sometime prior to 1879, now the Post Office Pharmacy. In 1881 the building was used to house the Franklin County Library. In the late nineteenth century, the library was displaced by the community's first pharmacy and post office. Although this building retains it's historic association with the district, its architectural integrity has been compromised by the complete alteration of its facade and interior space. Sometime in the period between 1879 and 1890, the third and largest of Miller's Second Empire style buildings still standing in the historic district went up— a three-story, wood-frame clapboard building at 48-50 Main Street.

At a later date, a shallow brick front with two storefronts was added, no doubt to conform with the later and more imposing masonry buildings on the street. Although much of the original structure retains substantial integrity of materials and design, the building derives its primary significance from the early twentieth century facade that completely changed its appearance.

In 1883 Dr. Trudeau built a sanitarium at Saranac Lake for patients of moderate means. Trudeau's unique situation is what made Saranac Lake the leading health resort that it became. He was a doctor, with sufficient training to follow new scientific developments; he was a sick man, motivated by his wish for health for himself and all others. His idea of a sanitarium was motivated by a charitable impulse, to help the less fortunate. His model was Dr. Hermann Brehmer's fresh air sanitarium in Goerbersdorf, Germany, the first successful institution of its kind in the world. In transplanting this idea to the United States, Trudeau first applied hard science to what had been essentially the folk medicine of climatic treatment by advocating a rest cure in the fresh air— the "Outdoor Life." His contribution was not one of discovery, but of synthesis—putting the ideas of others to the test of application. Remarkably, he did this twice: first in applying Brehmer's sanitarium idea to the United States; second, in founding the Saranac Laboratory for the Study of Tuberculosis, based on the work of Robert Koch in Germany. Little Red, the first building at Trudeau's Adirondack Cottage Sanitarium, located several miles outside the developing business district of Saranac Lake, was built in 1884.

By 1890 activity building in the village had begun a period of rapid growth spurred on by the growth of the Adirondack Cottage Sanitarium that would last for the next twenty years, imbuing the community with a boom town economy and spirit. To deal with this growth, the village of Saranac Lake incorporated in 1892, the first in the Adirondacks to do so, electing Dr. Trudeau as mayor and Miller as one of the first two trustees. During the next ten years, ten business blocks were built, of a large size and sophisticated style for what was still a remote area. Beginning with 4-6 Broadway, then still called Depot Street, the business section, still interspersed with houses, stretched down the hill to another crossing of the Saranac River and beyond. Nine of these commercial blocks (the Kendall Building at 82 Main Street, the McIntyre Block at 4-6 Broadway, the Ayer Block at 10 Broadway, Scheefer's Jewelers at 20-22 Broadway, Leonard's Department Store at 85 Main Street, the Harding Block at 89 Main Street, the Loomis or Downing Block at 15-17-19 Broadway, the Ledger Block at 25 Broadway, and Stark's Hardware at 29 Broadway) are modest vernacular examples of popular nineteenth-century commercial architectural styles. These early buildings reflect their remote location through their builders' use of local materials and simple fenestration; they also reflect the conservative approach of their builders to the onset of an unprecedented prosperity. Three of these, Leonard's Department Store, the Harding Block and the Ledger Block (as well as the Coulter Block at 71-79 Main Street and the Hogan Block, just out of the district) were built in two parts, expanding onto an adjacent site as business warranted, or funds allowed. The cautiousness of this approach reflects the unanticipated growth of Saranac Lake as a health resort.

The Coulter Block at 71-79 Main Street, as the first of the buildings in the district known to have been architect-designed, marks a transition. William Lincoln Coulter came to Saranac Lake for his health, opening his office in 1895, probably the first architect to establish a practice in the area. He had apparently studied architecture at Columbia University, but did not graduate. He spent twelve years in practice at Saranac Lake, during which time he became regionally recognized for his work on many of the large, sophisticated "Great Camps" built for the wealthy in the region.

The first building known to be his work is the imposing cobblestone and shingle Main Building at the Adirondack Cottage Sanitarium, built in 1896. In 1899 and 1900 Coulter, perhaps for office space for his practice, purchased two lots on Main Street and oversaw the progressive construction of two buildings, internally linked above the first story, known together as the Coulter Block and bought and sold as a unit ever since. Acting as a developer, Coulter gambled on the mercantile future of Saranac Lake, yet the building's two-part construction drew upon the conservative attitude of those who preceded him. It is during this period in his career that Coulter established himself as one of the premier architects of the Adirondack "Great Camp" era. At the turn of the century Coulter took on a partner, another patient, named Max Westhoff. By 1902 the firm had designed many residences that incorporated camp style architecture with open verandas and the sleeping, or cure, porches that had become associated with Trudeau's fresh-air cure. In 1905, William Distin,Sr., son of an early local photographer, joined the firm. Coulter died in 1907.

The first years of the new century saw nine more new buildings added in the Berkeley Square district. In these years, the character of the Main Street section changed radically as guides' houses were replaced by commercial buildings. Moreover, this section of the downtown (which extended north across the river for several blocks as early as 1895) became the showcase for expensive consumer goods in expensive buildings, designed to attract and satisfy the wealthy patients flocking to try Trudeau' s cure. In August 1906, Reuben and Ida Reynolds sold the house they had rented to the Trudeau family to the Adirondack National Bank, which in turn sold the south half of the lot to the Hudson River Telephone Company for the Telephone Exchange Building (68 Main Street) and built an elegant bank for its own use on the north half, at 70 Main Street. Also constructed during this period were: the Walton and Tousley Hardware Store at 34 Main Street, the Donaldson Block at 56 Main, the Haase Block at 60 Main, the Fowler Block, or old Enterprise building, at 76 Main, the Roberts Block, or Finnigan's, at 78 Main, the Jack Block at 2 Broadway, the Egler Block, or the Fair Store, at 18 Broadway. Built between 1900 and 1912, these buildings show increasingly elaborate detail reflecting the Colonial and Classical Revival styles popular in this era and clearly illustrating the willingness of their builders to make substantial investment in quality design, construction and ornamentation. Three of these buildings also represent outstanding surviving examples of a type of facility popular among turberculosis patients, apartments with galleries and balconies overlooking the street on the second and third floors of business buildings. Like many such facilities constructed in Saranac Lake for use by patients, those in the Berkeley Square district were privately developed in a community acutely sensitive both to the needs of its market and to the latest medical wisdom as expressed in the building trends at Trudeau's sanatarium. In Saranac Lake both developers and architects were also often tuberculosis patients; it seems likely that they would be especially interested in developing specialized facilities in a rapidly growing and urbanizing downtown district.

In an article titled "Evolution of Sanatorium Construction" published in the Journal of the Outdoor Life in May 1935, the architects William H. Scopes, A.I.A and Maurice M. Feustmann, A.I.A. described the changing uses of porches:

The porches of the early cottages (at the sanitarium) were small and had no protection from the wind other than the protection provided by the cottage walls....The most important change... came with the advent of outdoor sleeping. In one of the cottages that was being built at Trudeau at this time (1902-Richardson Cottage), work had gone too far to make the needed changes so that each patient could be wheeled directly from a room to the porch.... After this no cottage was built at Trudeau or any patient housing provided without arrangements for direct access to a porch from the patients' rooms.

The planning at Trudeau Sanatarium had its influence also on residential construction in Saranac Lake. From time to time many cottages had been rented by patients in Saranac Lake Village, hardly any of which were provided with sleeping porches, prior to 1900. Commencing at that time, however, it was almost impossible for a house owner to rent his cottage unless it had one or more sleeping porches.

Note: The term "porch" is used in the modern sense of a covered veranda or open room exposed to the atmosphere. Loggia might be a more accurate description for multi-storied buildings.

In Berkeley Square, the attempt to accommodate tenants who might also be patients is reflected in a variety of sitting-out porches which were built into the downtown business blocks as a part of the original intent of their designs and in the wood-frame sleeping porches which were probably added to some of the buildings that had been built earlier without such facilities. Included in a list of downtown buildings that still exhibit some cure-related features are five buildings with intact verandas, balconies or galleries: the Haase Block at 60 Main Street, the Fowler Block at 76 Main Street, the Roberts Block at 78 Main Street the Harding Block at 89 Main Street, and the Loomis or Downing Block at 15-17-19 Broadway. Two others retain evidence of such use, although the buildings have been altered, the Donaldson Block at 56 Main Street, with its Gibbs surround, now enclosed, and the McIntyre Block, 4-6 Broadway, with a sleeping porch on the second story front in the domestic style of attached porches, the only such example on the front of any building in the district. The formal, masonry business buildings have essentially been provided with second and third story verandas, for sitting out. Those facilities added later, probably the case with 4-6 Broadway, were likely designed as sleeping porches, enclosed with glass and, ideally, opening directly from bedrooms.

The Colonial Revival Fowler Block at 76 Main Street was the first building in Saranac Lake designed by architect William Henry Scopes, who came to the village from Utica in 1889 to cure. While occupying Little Red at the sanatorium, he became interested in architecture and took a correspondence course in the subject. He later went to Columbia University for further study and began practicing in 1903. The Fowler Block was designed during Scopes's period of study, prior to the opening of his office in Saranac Lake. He is also known to have designed many of the cottages at Trudeau's sanitarium during this same period.

Maurice M. Feustmann became Scopes's partner in a productive and long-lived firm responsible for most of the civic monuments in the village. Feustmann was a graduate of the University of Pennsylvania and studied in Munich for two years. He also studied at the Ecole des Beaux-Arts in Paris and in other parts of Europe. He came to Saranac Lake at the close of the last century when his health became undermined, remaining for two years before going to the southwest to continue the cure. In 1903 Scopes invited him to return to Saranac Lake and form the firm of Scopes and Feustmann. The offer was accepted and the firm won its first competition in the bidding for the contract to design the Reception Hospital. The names "Scopes and Feustmann" became inseparable, and it is difficult to distinguish the contributions of the individual partners. Their names appear on drawings for private cottages, many institutional buildings at the sanitarium, public buildings in Saranac Lake, and other sanatoria in Vermont, Georgia and Liberty, New York. Scopes and Feustmann became internationally known authorities on the design of sanatoria for the cure of tuberculosis. Both were members of the American Institute of Architects, and Scopes was honored in 1956 for "long and distinguished service" to his community by the Central New York Chapter of the A.I.A. Feustmann died in 1943 of a heart illness, but the long list of buildings to his firm's credit shows no work locally after 1930, when new construction had nearly ceased entirely. Scopes died at 87 in 1964, his cure successful; he is buried in Pine Ridge Cemetery. Locally, they designed the Hotel Saranac, Will Rogers Hospital (National Register listed), and, in Berkeley Square, the 1907 Haase Block and the 1926 Harrietstown Town Hall, as well as the 1918 oak storefront remodeling at 89 Main Street.

Finally, the 1920s saw the last two available sites in the Berkeley Square Historic District built upon. The Tousley Storage Building at 38-40 Main Street, built as a parking garage and Dodge sales agency, is in a commercial style marked by Tudor arches and a glazed terra-cotta facing. The Book Store, designed by William G. Distin, Sr., is a modest Art Deco style storefront with bronze trim and black granite base. The building at 84 Main Street was designed by architect Paul Jacquet on the site of a building torn down to make room for it. Two other new buildings replaced two which had burned, Altman's on the site of the Central Hotel and the new Harrietstown Town Hall on the site of the old one.

The Harrietstown Town Hall, the only public building in the historic district, is an expression of Saranac Lake's prosperity in 1926, the year that the old town hall burned and taxpayers voted to build the fine new one. The architects were Scopes and Feustmann. Like Milo Miller sixty years earlier, the architects interpreted a sophisticated popular style in more modest materials— red brick and Indiana limestone. The town hall remains one of the finest examples of Beaux-Arts influenced civic architecture in the region.

The Berkeley Square Historic District clearly reflects the development of Saranac Lake into the premier health resort of the late nineteenth and early twentieth century. This highly intact grouping of commercial buildings, which represent the nationally popular architectural styles of the day, is further enhanced by the adaptation of these styles by the builders to incorporate design elements brought to the area by Dr. Trudeau as part of this tuberculosis cure program. The Berkeley Square Historic district represents an unusual urban commercial streetscape that still remains isolated in the midst of the Adirondack wilderness.

See also

Source