The Loomis Block

The Loomis Block  Loomis Cash Store (undated, but not later than 1940). The clock face reads "10% Loomis Cash Store." At left is Woodruff Street, at right, the Berkeley House. Historic Saranac Lake collection

Loomis Cash Store (undated, but not later than 1940). The clock face reads "10% Loomis Cash Store." At left is Woodruff Street, at right, the Berkeley House. Historic Saranac Lake collection  1927 Canaras Address: 14 Broadway

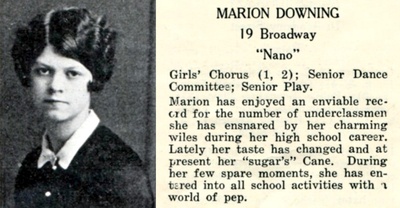

1927 Canaras Address: 14 Broadway

Old Address: 15-17-19 Broadway

Other names: Downing Block, Forest Home Furnishings

Year built: 1896-99; 1908

This building is one of three situated on lots that were sold by Russell Eugene Woodruff.

R. Eugene Woodruff was one of Saranac Lake's earlier developer/ builders. He is best remembered as being the contractor who built St. Luke's Church (1879) in the Church Street Historic District.

In the late 1870s and throughout the 1880s, Woodruff amassed substantial acreage along the Saranac River below Broadway. Through this land he made a street, and near the downstream end of it he built a lumber mill. The mill is gone, but the street remains and bears his name.

In August, 1896, Woodruff sold a 5840 square foot lot at the south corner of Broadway and Woodruff Street to Frederick W. and Hattie D. Loomis. The price was $1500 for part of a lot the seller had bought for $100 not quite 20 years before.

The Loomises built a three-story brick building that pretty much filled their new property at 19 Broadway. Fred Loomis then opened a store which occupied nearly all of the ground floor. This was Loomis' General Store. It was a major supplier of such items as packbaskets (they hung all around the walls), traps, and hunting equipment. It was also the primary outlet for school supplies and the sole distributor of text books.

Until fairly recently, Saranac Lake High School students did not get textbooks gratis from the school district and the State Education Department— they had to buy their own. Fred Loomis had the contract to sell them, and he made sure he had in stock exactly which books were needed but always a few more of each than were initially required. The difference between this approach and that of E.L. Gray (who took the distributorship after the Loomises left town and who was always coming up short) was the difference between satisfaction and headaches — and satisfaction meant profits.

Fred Loomis retired and he and Hattie sold their building to George B. and Annabell "Belle" Downing in October, 1920. They moved away to Vermont; and when Fred died, he left $350,000 to the Fresh Air Fund — an organization that arranges summer vacations for inner city children with participating Fresh Air families in the North Country. [See article below from the New York Herald Tribune for a somewhat different version.]

When one looks at the Loomis Block today, one sees four storefronts — a large one on the corner and three smaller ones south of that. In the southern-most of these — a very long and narrow space — George Downing and Grant Cane opened a restaurant that became as popular, with a different set of people, as was the Blue Gentian.

The clientele at Downing and Cane's, with Micky Cimbric behind the bar (the Blue Gentian had no bar), was primarily young, extroverted, gregarious. Many of these people were in the process of curing. Tuberculosis was a young person's disease, and the village was full of men and women in their 20s who were lusty and bright and vitally alive regardless of the fact that their lungs harbored a deadly bacteria. The truth of the matter was that many who came to Saranac Lake were only marginally afflicted and were receiving the best of care. Furthermore, if correct hygiene were practiced, tuberculosis was not the galloping contagion that people not familiar with it feared.

So, the young patients came to Downing and Cane's (sometimes looking a good deal more healthy than the non-patients).

The restaurant was the social hot-spot of the village. Also, located adjacent to the Pontiac Theater, Downing and Cane's became the place to go after the movies. Often, between shows, there would be two lines of people on the sidewalk — one in front of the Pontiac and one in front of Downing and Cane.

After George Downing's death in 1954, Grant Cane moved the restaurant to the Thompson Building, though Belle Downing retained ownership of 19 Broadway.

Downing and Cane went out of business in the mid-1960s. Belle Downing died in 1972; and, in November of that year, the executrices of her estate sold the Loomis Block to Edward J. Dukett, a local man who owns several residential buildings in the village. Some years ago, Mr. Dukett put a wood-burning boiler in 19 Broadway, and in the 1980s the Loomis Block was the only building in the District (and probably the only major commercial building in the area) which obtained heat and hot water exclusively from wood fire.

Sometime between 1920 and 1930, fire gutted the upper story of the Loomis Block. This was cut down to just above the second-story ceiling level, and a new roof was built. The roof has seven skylights. Later still, the street sides of the brick exterior were stuccoed.

The four entryways to the storefronts and the residences upstairs are all under segmental arches of varying span; and the space between the display windows and the floor above is filled with Luxor prisms. Unfortunately, they have all been painted. The ground-floor storefront trim is bronze.

Running the entire length of the Woodruff Street and Broadway sides of the second story is a veranda with a very small, recent enclosure at one end. The roof of this veranda, 135 feet long, is supported by unadorned, wooden pillars joined by gently arched tie-beams that, at their apexes, touch higher, straight tie-beams.

The veranda is the outstanding feature of the Loomis Block, but it needs some repairs — especially one section of its railing. The building in general could use a new coat of paint; but is in relatively good condition.

Original text by Philip L. Gallos, 1983

Albert Charles Bagdasarian stayed here.

Sources:

Adirondack Daily Enterprise, May 1, 1993

Remembering the days of the Merchant of Saranac

A 1906 advertisement for the. F.W. Loomis store at 17-21 Broadway in Saranac Lake listed everything from eyeglasses and skates to Edison talking machines and packbaskets. Watches, clocks, and jewelry headed an impressive roster of some 65 items for sale. This remarkable emporium was situated in what later became known as the Downing Block at the corner of Broadway and Woodruff streets. Over the entrance was a sign in the form of a huge pocket watch which boasted "10% Loomis Cash Store."

Frederick W. Loomis was born near Liberty Hill in Connecticut in his grandfather's farm house and as a young man moved to Saranac Lake. He entered into business with great enthusiasm, as signified by his huge assortment of merchandise. Originally called a sporting goods store, the stock soon branched into the wide variety of household appliances, dry goods, and confectioneries. His stated claim in print read "I intend to keep a good assortment of the following lines of goods that will give satisfaction." This announcement was followed by the long list mentioned above.

Mr. Loomis proved to be an astute merchant and his tenure as a shopkeeper coincided with that era of prosperity related to the health cure industry in our village. Despite his obvious success no one seemed to realize the immensity of his acquired wealth until after his death. This became known after his retirement and return to his original home in Connecticut, where his final attempt at operating a store was an actual farce when compared to his Saranac Lake activity. More about, this later.

According to one story that has been handed down, Loomis did not always adhere to the maxim that the customer was always right. When he matured, he had reached the portly weight of 250 pounds and had a ladder mounted on wheels which could roll the full length of the store to reach those wares resting on the top shelves. One day a woman wandered in to purchase a roll of cloth featuring a floral pattern. Up the ladder went Loomis, who came down with a bolt of material which he unrolled on the counter. The lady approved the design but then said "How much is it?" Upon hearing the price she remarked, "My, that's pretty high isn't it?" Without hesitating Loomis rolled up the bolt, started back up the ladder, and said over his shoulder, "It's going higher!"

The early 1900s in our village proffered a wide choice in commercial services. There were several grocery stores, butcher shops, fish markets, bakeries, clothing stores, shoe stores, drug stores, bottling works, dairy stores, green grocers, livery stables, stationery shops, hardwares, millinery shops, and many more hotels than are present today. The Loomis emporium was situated in the center of the business district where the flow of shoppers had to pass under the large watch. Apparently a goodly number entered the premises. As today's malls offer one-stop shopping, Loomis preceded the trend by offering his huge variety of common needs to the shopping public. The housewife could purchase pots and pans while her husband could buy a rifle and ammunition. There was very little on any shopping list that could not be found on the Loomis shelves.

The neighboring campers from the Saranac and St. Regis lakes came into the village for many of their supplies. Two such customers became frequent visitors to the Loomis store. Whitelaw Reid, publisher of the New York Tribune, and Dr. Walter B. James, a trustee of the Tribune Fresh Air Fund, from Camp Wildair on St, Regis Lake, became friendly with the store's proprietor. It seems certain that the Fresh Air Fund was a topic of conversation during such times when the men met but apparently there was no commitment mentioned regarding the fund. Neither of the two visitors suspected the final result of the casual relationship which had developed in the variety store.

After his wife died, Fred Loomis decided to sell his store in 1915 and return to his former home in Connecticut. Packing up all of the unsold articles from Saranac Lake he opened his final store in an old building next to the Chestnut Hill New Haven Railroad siding depot. Here he settled down to relax in an atmosphere closely resembling that of a recluse. In an overstuffed chair that molded itself to his bulky torso, he was content to exist among his average inventory making absolutely no effort to sell any of the relics transported from Saranac Lake. An attempted robbery caused him to hire a bodyguard, who sat in the store with a shotgun across his lap. The same price tags of some 30 years earlier remained on the merchandise resting on the dusty shelves. He seemed to enjoy conversation with the very few would-be customers who managed to discover the remote establishment, but was reluctant to leave his seat to make a sale.

Loomis had a home nearby but regularly slept in a room over the store where his bed was directly above the massive safe on the floor below. He normally kept an open shop until 10 p.m., when he would retire to his upper chamber. His only ventures outside were short trips in his horse-drawn wagon while neighbors discreetly observed that the horse was just as fat as Fred.

On a September morning in 1939 his bodyguard-caretaker was arriving to assume his daily duty when he found Fred lying unconscious on the floor. He could not lift the heavy body so he summoned help and managed to get Loomis to a hospital where, when he came to, the patient was very unhappy at being restrained. When it became apparent that his prognosis indicated that the heart attack might very well be life threatening his friends came to ask for the combination to his safe so that they could begin to put his affairs in order. Loomis slyly gave them a batch of wrong numbers.

After his death at age 74 on Feb. 10, 1940, a locksmith was authorized to open the safe. The contents disclosed a large assortment of jewelry from his Saranac Lake emporium but the big surprise came later with the reading of his will. His entire estate, valued at $115,000, was left to the Tribune Fresh Air Fund. Dr. James stated that it was the largest single contribution ever donated to the fund.

There was no doubt but that this huge fortune had been amassed during his business years at Saranac Lake. After returning to Connecticut in 1915 Loomis wrote a letter suggesting that his Liberty Hill property could be used for a children's summer camp, but nothing developed from the offer. It remains, however, that his intentions were clearly aimed at providing charitable support for the Fresh Air Fund and his final philanthropy settled the issue.

Thus it came to pass that a chance meeting in the store at No. 21 Broadway in Saranac Lake led to the provision of countless summer vacations for city children who could for a brief period escape their slum surroundings for a breath of Adirondack air. Fred Loomis possessed a heart as big as its containing body.

From the New York Herald Tribune, "Fresh Air Fund Willed $115,000 By Storekeeper," March 2, 1940:

COLUMBIA, Conn. — Frederick W. Loomis, who operated what was undoubtedly the strangest general store in eastern Connecticut until he died of coronary thrombosis on February 10, has left his entire estate, valued at more than $115,000, to the Tribune Fresh Air Fund . . . [After naming the parts of the estate in Connecticut, the article states:] There is an additional half-acre in Saranac Lake, N.Y., where Mr. Loomis apparently amassed the bulk of his fortune as the proprietor of a large sports and general merchandise store which he sold about twenty-five years ago. . . . Born in Liberty Hill, he went to Saranac Lake as a young man and started a sports goods store. The business prospered and developed into a large emporium. On the curb, Mr. Loomis installed a big clock with the letters: "10% Loomis Cash Store." Among his customers were the late Whitelaw Reid, editor of "The New York Tribune," whose Camp Wildair was nearby, and the late Dr. Walter Belknap James, a trustee of the Tribune Fresh Air Fund. . . . Mr. Loomis returned to Liberty Hill following the death of his wife, the former Harriet Cleland. He had a lot of odds and ends left over from his Saranac Lake business, so twelve years ago he opened the little store opposite the Chestnut Hill depot.

In a photo caption, the Tribune erroneously reported that the Loomis Block was no longer standing.

Adirondack Daily Enterprise, "Blaze rips through Broadway storefront," February 21, 2002:

Flames plumed from the Forest Home Furnishings storefront this morning, and smoke spilled out of several other storefronts in the same building. Saranac Lake volunteer firefighters used hoses, axes, crowbars and power saws to get at the fire inside the walls of the building at 15-21 Broadway. They pried off much of the facade and pulled away a chunk of the brick wall to do so. "It probably wouldn't have been much longer before the whole building went up," Fire Chief Ed Woodard said. The fire was extinguished before press time, and an investigation began to find out what caused it. Woodard said it started below a radiator in the front corner of Forest Home Furnishings. "It looks like electrical," Woodard said of the cause. . . .

Adirondack Daily Enterprise, December 1, 1972

Edward Dukett of 33 Riverside Drive is the new owner of the Downing Block, 19 Broadway. The only change he has in mind is splitting the large apartment into two smaller apartments.

George Downing bought the building about 50 years ago from Mr. Loomis who ran a small department store. One of the humorous incidents a townsman recalls was the day a woman, intent on buying a pack basket, told Mr. Loomis the price was too high. He then threw the basket in the air, saying, "It's going higher," and tossed it back up the shelf. No sale.

There are probably those who remember the former tenants of the building: Wilson's haberdashery, replaced by Town and Country, Sullivan's Tobacco Shop, now occupied by Books 'n Cards; and Downing and Cane's restaurant which is now Chuck Pandolph's bar.

The Guild News, March, believed to be 1945

Home Town Jottings

Fire which swept the top floor of the Downing Block on Broadway also did much damage to the second floor, and to the Wilson Clothing Co., Sullivan Cigar store, and Downing and Cane's Tap Room, on the street level. Firemen from Saranac Lake and Lake Placid fought the flames for three hours and were able to confine them to the third floor. Many of the tenants, including Bill Sullivan and Albert Bagdasarian lost all of their belongings. Repairs are underway and it is expected that the building, minus the top floor, will be inhabitable by April 1st.