From the Adirondack Daily Enterprise, September 11, 1986

A most extraordinary meeting of the minds

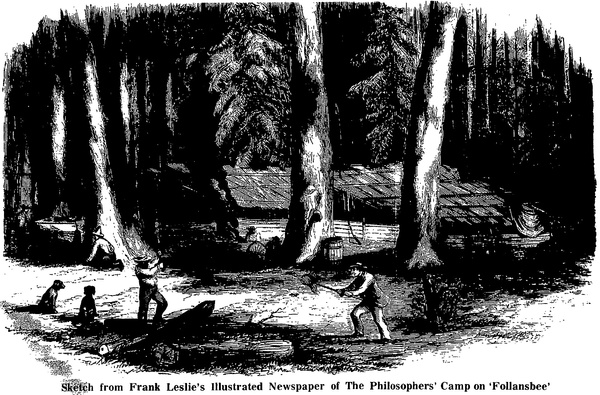

The Philosophers' Camp

Down through the years many writers of Adirondack history have told the story of the famed "Philosophers' Camp," including contradictory versions by Donaldson and Headley. The most authoritative account, however, can be found in the pages of Stillman's "Autobiography of a Journalist." His is the most reliable coverage of this subject for the simple reason that he was there. In fact, he was not only present but was also the organizer and self-appointed leader of that expedition of intellectuals heading for the northwoods in the summer of 1858.

William James Stillman was born in Schenectady in 1828 and received formal education at Union College in that same city, graduating in 1848. Completion of his academic stint freed him to follow his main ambition, that of becoming an artist. He enrolled in a class under the able tutelage of Frederick E. Church, head of the Hudson River School of landscape painting, and then sailed for Europe to rub elbows with Rossetti and Millais of the Pre-Raphaelite art set. These encounters sent him back to America with zealous ambitions.

The Philosophers’ Camp in the Adirondacks, William James Stillman, 1858

The Philosophers’ Camp in the Adirondacks, William James Stillman, 1858

Concord Free Public Library William Munroe Special Collections

Returning to Schenectady, he met a fellow painter, S.R. Gifford, who encouraged Stillman to seek fresh inspiration and strongly recommended the Adirondacks as a promising source. Heeding this advice, Stillman was soon lodged in the Johnson cabin on the shore of Upper Saranac Lake where he spent the entire summer of 1854. Here he paid the sum of two dollars per week for room, board, and the privilege of painting all landscape scenes, courtesy of the bucolic landlord of this rustic manor. The young artist immediately fell in love with the region, an infatuation that would inexorably draw him back to these wilderness haunts throughout his lifetime. In addition to his paintings, Stillman applied himself to mastering those related skills of woodcraft peculiar to the native guides. He soon became proficient with rifle and rod, with axe and oar; and although slight of build, could shoulder his packbacket and boat over the carries.

A Metamorphosis

At this point a metamorphosis was taking place whereby the aristocratic artist was fast becoming the accomplished woodsman. He reveled in the vast solitude of the wilderness and loved to wander the trails and waterways with nomadic abandon. Three months of this lotus-living finally ended in a return to New York City where he rented a small studio and began publishing a little art weekly named The Crayon. Sharing the magazine with items d'art, there appeared exciting accounts of his Adirondack experiences. In search of literary pablum to nourish his infant periodical, Stillman decided to visit that inner sanctum of prose and poetry centered in the Boston-Cambridge hub. Demonstrating an uncanny ability for making the right social contacts, he soon met Longfellow, Lowell, Emerson, Holmes and Norton while attempting to secure articles for "The Crayon." So favorable were these meetings that Stillman decided to move operations to Cambridge.

Despite all the glitter of his new surroundings, he still managed to make repeated runs to his beloved Adirondacks. It soon dawned on him that perhaps he could interest some of his elite friends to share in the Adirondack experience. Upon each return to Cambridge there would be an enthusiastic report extolling the thrills of camping out in the mountains and his preaching finally won some converts. A party was formed consisting of John Holmes (brother of Oliver Wendell), James Russell Lowell together with his brother-in-law Dr. Estes Howe, and two nephews.

Happily assuming the mantle of guide, Stillman brought his little group to Martin's Hotel on the shore of Lower Saranac Lake where he always started his sojourns into the wilderness. From this point the party cruised the Saranacs, the Raquette River into Tupper Lake, and wound up the trip at Raquette Lake. It was a most enjoyable vacation and upon their return home his newly-won disciples spread the gospel that Stillman spoke the truth. Winter meetings at the Saturday Club proved to favor a larger contingent for the next season and our guide basked in the limelight.

Meeting of the Minds

The main event took place, during the summer of 1858 when ten of the most illustrious intellectuals ever to camp out in the Adirondacks met for a vacation holiday. The party consisted of: Ralph Waldo Emerson, Louis Agassiz, James Russell Lowell, John Holmes, Horatio Woodman, Ebenezer Rockwell Hoar, Jeffries Wyman, Estes Howe, Amos Binney and, of course, Stillman. Also invited, but who could not make the trip for diverse reasons, were Oliver Wendell Holmes, Henry Wadsworth Longfellow and Charles Eliot Norton. Longfellow stated that if Emerson took along a gun someone would be shot. Emerson did; nobody was.

Boats and guides were assembled at Martin's dock awaiting the arrival of the elite company. Also waiting in the wings was a delegation from the tiny hamlet of Saranac armed with a portrait of Agassiz for identification purpose. The famed Swiss naturalist had recently turned down an offer from France to come to Paris as a senator and keeper of the Jardin des Plantes. Agassiz chose instead to become professor of zoology at Harvard and therefore had become a national hero. When the stagecoach arrived, the local deputation pushed eagerly forward and compared the disbarking faces to their engraving. When identification was made each hurried to shake hands with Agassiz while completely ignoring the rest of the party of dignitaries.

Stillman and his guide, Steve Martin, had previously selected the campsite where they built an open shelter of poles and bark to house the guests. In Stillman's own words they chose a "deep cul-de-sac of lake on a stream that led nowhere, known as Follansbee Pond." The spelling has since been changed to Follensby. The little flotilla left Martin's, cruising through the chain of Saranac Lakes, and arriving at the Indian Carry the boats were portaged overland to the Raquette River. Rowing downstream for some four miles, the guides led them off the river and into a narrow twisting stream which finally opened on "Follansbee's" sparkling waters. The open camp, which Stillman had prepared, was situated between two huge maples, which inspired Lowell to name the site "Camp Maple." The guides, however, re-christened the place "The Philosophers Camp" and, needless to say, the latter caught on.

The Daily Routine

A common daily routine consisted of shooting at the mark, hunting, fishing, swimming; and evening seminars around the fireplace. The menu featured Venison, trout, grouse, and such staples as salt pork and potatoes all washed down with "foaming pans of ale. When the- larder needed replenishing the hounds were put out to drive deer to the water where they were dispatched by guide or guest. A night hunt also produced venison with the help of a jacklight.

Set lines were baited in the evening for lake trout and were hauled out on the following morn. At a later date all three activities were outlawed by the Forest, Fish and Game Commission.

Longfellow feared that if Emerson took along a gun someone would be shot. Emerson did; nobody was.

Stillman chose to act as guide for Agassiz and each of the other members had his own guide and boat. Some would explore the nearby woods and waters while Agassiz and Wyman enjoyed the opportunity to "dredge, dissect, and botanize." With such literary champions condensed and isolated in wilderness solitude, a great deal of social repartee obviously took place. As darkness gathered Emerson liked to row out on the lake to observe the "procession of the pines." This phenomenon was usually shared with Stillman who was constantly trying to probe Emerson's deepest thoughts. The two men shared a common interest in nature, philosophy, and such hypothetical subjects as ESP and transcendentalism. Although Agassiz was considered to be the camp favorite, in Stillman's eyes Emerson was its outstanding figure. Every member of the party thoroughly enjoyed the wilderness adventure, giving Stillman a full vote of confidence, and made it apparent to the extent that thoughts already were turning to a repeat performance as the final days of vacation were drawing to a close. When the fun was all over, the nine guests returned to their homes, but Stillman remained in camp to paint.

The Adirondack Club

Later that fall the entire company met to organize the Adirondack Club and plans were drawn to establish a clubhouse where all members could enjoy a continuity of their recent adventures. The group decided to purchase property where a permanent building could be erected and, quite naturally, Stillman was elected to oversee the project. So back he went to Martin's, although cold weather was approaching. After consulting with Martin he learned that a prime parcel of 22,500 acres containing Ampersand Pond was recently forfeited to the state for back taxes. He was able to purchase the tract for $600 and immediately reported the good news to his fellow members. The property was secured-and Martin was hired to build the camp since Stillman had fallen victim to a siege of pneumonia.

The cabin was ready for the summer of 1859 and Charles Eliot Norton and Samuel G. Ward were added to the membership. Stillman claimed that Ampersand was even more beautiful than Follensby and the season was most successful. The success was destined to be short-lived. Stillman sailed once more for Europe and his leadership was sorely missed. The gathering clouds of the Civil War brought the final blow to the Adirondack Club and, the property again reverted to the state for taxes. Lowell's two nephews, who made the first trip with Stillman, were both killed in the conflict.

Emerson's epic poem entitled "The Adirondacs" (perhaps he felt the letter "k" to be superfluous) described in full the camp activities at Follansbee:

"All day we swept the lake, searched every cove, North from Camp Maple, south to Osprey Bay, Watching when the loud dogs should drive in deer, Or whipping its rough surface for a trout; Or, bathers, diving from the rock at noon; Challenging Echo by our guns and cries; Or listening to the laughter of the loon..."

In his Early Years of the Saturday Club, Emerson offers a verse sketch of Stillman, again in part:

"Gallant artist, head and hand, Adopted of Tahawus grand, In the wild domesticated, Man and mountain rightly mated, Cart hunt and fish and rule and row, And out-shoot each in his own bow, And paint and plan and execute Till each blossom became fruit..."

Stillman later became U.S. consul in both Rome and Crete and served as correspondent for the London Times in Italy and Greece. He retired to Surrey, England in 1898 and died there on the 6th of July 1901 ending a most extraordinary career in many variegated fields.