I. - Early Settlement (1819-1860)

During the Seventeenth and Eighteenth century, most residents of the Adirondack wilderness were native Americans. Camping sites on the shores of both Upper and Lower Saranac Lakes have yielded artifacts used by native peoples in hunting and fishing. Members of the Iroquois, Abenaki, and Huron nations used the uplands regularly as well as the lower elevations.

A small island in Lower Saranac Lake

A small island in Lower Saranac Lake

New York State first claimed the unappropriated lands of the Adirondacks in 1781 to serve as bounties for militiamen who served in the Revolutionary War. The 665,000 acres which are now Clinton County and parts of Franklin and Essex Counties were surveyed in 1786 and divided into ten-mile-square townships, but few soldiers were willing to take the rugged, interior lots. New York State later set aside additional lands in central New York to be used as military bounties, and these lots in the Adirondacks came to be known as the "Old Military Tract." The westernmost line of the Old Military Tract became the Franklin-Essex County line which still divides the village of Saranac Lake today.

New York State next offered the land within and to the west of the Old Military Tract for sale to investors and developers. On June 22, 1791, Alexander Macomb purchased 3,693,755 acres between Essex County and Lake Ontario, the largest grant of land ever made by the State of New York. His parcel included Franklin County and the western portion of what came to be the Village of Saranac Lake. Most of this tract was later sold to William Constable, who named the town of Harrietstown after his daughter.

Settlers were slow to move into the mountainous regions of the Adirondacks since better farmland was more easily reached elsewhere. The great flood of emigrants from New England bypassed the Adirondack wilderness because of its inaccessible terrain and difficult climate, moving further westward instead, through the St. Lawrence River Valley to the north or along the Mohawk River Valley to the south. Not until c.1800 did the inner valleys of the High Peaks region begin to have permanent settlers, when the Northwest Bay Road was cut through the wilderness from Westport on the shore of Lake Champlain northwest through Elizabethtown and Keene. Between 1810 and 1817 a series of Legislative appropriations were created to improve, upgrade and extended the Northwest Bay-Hopkinton Road northward to Hopkinton in St. Lawrence County, crossing the Saranac River where the Baker bridge stands today.

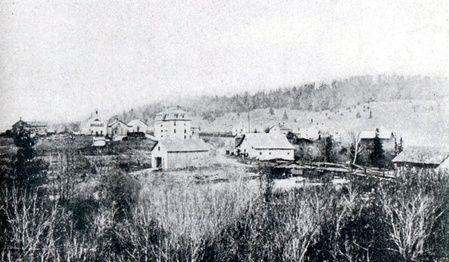

Earliest known photograph of Saranac Lake, 1877, by George W. Baldwin, looking up Berkeley hill from the Saranac River. Berkeley House, with the mansard roof is just left of center. The Old Academy is the white building left of the Berkeley.

Earliest known photograph of Saranac Lake, 1877, by George W. Baldwin, looking up Berkeley hill from the Saranac River. Berkeley House, with the mansard roof is just left of center. The Old Academy is the white building left of the Berkeley.

The Saranac Lake area was first settled by Jacob Smith Moody who built a cabin and cleared land in 1819 along the Northwest Bay Road. (The road still exists, now known as Pine Street within the village limits and Old Military Road in the Highland Park Historic District.) Moody owned sixteen acres of land which included the back of Helen Hill, Pine Ridge Cemetery (which contains his family graveyard), and Moody Pond.

In 1822, Captain Pliny Miller from West Sand Lake, Rensselaer County, the former commander of a militia company in the War of 1812, purchased 300 acres of land along the Saranac River in what is now Franklin County. His Wilmington, New York, lumbering business had been forced into bankruptcy by the failure of his primary Canadian customer, and he hoped to begin again in the Saranac Lake area. Much of the village of Saranac Lake stands on Miller's original purchase of land. In 1827 Miller built the first dam across the Saranac River to power his sawmill, creating a large mill pond where logs were gathered each spring for processing. This pond — large enough to be called a lake — was cleared of tree stumps in the 1890s and renamed Lake Flower, in honor of New York governor Roswell P. Flower.

Colonel Milote Baker, the last of the village's three pioneer families, did not arrive from Keeseville until 1852, when he settled on the land where the Northwest Bay Road crossed the Saranac River. Two of his daughters (first Narcissa, then Julia) married Ensine Miller, son of Pliny, who also farmed and owned two sawmills and a gristmill. By 1876, his son Andrew, a successful guide, built Baker Cottage by Moody Pond, on what is now known as Stevenson Lane.

The early village grew up along the triangle of roads (now River, Pine and Main Streets) which connected the farms of these three families and encircled Helen Hill. [Map #11] Farming, lumbering, trapping, fishing, and hunting, they made their living from the land and the wilderness around them. The area's remoteness from markets and lack of sufficient local demand prevented any greater use of the resources available. Log drives along the Upper Saranac River occurred as early as 1847, floating the logs down to Plattsburgh on Lake Champlain, but mills to produce finished wooden products locally were not to be built for many more years.

In 1849 Miller built the area's first hotel across the river from his sawmill, on the site of today's village water pumping station. Two years later the manager of Miller's hotel, William F. Martin, built his own hotel on Lower Saranac Lake about two miles west of the village, the first hotel in the Adirondacks to actually be located within the wilderness, rather than within village limits. Big enough to house eighty guests, the Saranac Lake House, more commonly known as Martin's, was considered an outrageous folly by local residents when it was first built.

In 1851, the same year as the opening of Martin's, regular stagecoach service was established between Saranac Lake and villages along Lake Champlain where connections could be made with lake boats traveling north and south. Standing at the northern end of the route, at the gateway into the wilderness, Saranac Lake was ideally located to serve travelers and sportsmen exploring the wild hinterlands.

By the late 1840s, upper class urban dwellers had begun to rediscover and idolize untouched wilderness. Wealthy sportsmen, called "sports," from cities downstate came to the Adirondacks on holidays, hiring local men to serve as guides to take them into the wilderness camping, hunting and fishing. Because of the primitive camping conditions and rugged traveling, few women ventured into the Adirondacks as tourists. This began to change with the opening of Martin's hotel and, in 1859, Paul Smith's family hotel on the shore of Lower St. Regis Lake, about fifteen miles northwest of Saranac Lake.

Mitchell Sabattis (standing between trees) with fellow guides Farrend Austin and Johnny Keller behind their "sports"

Mitchell Sabattis (standing between trees) with fellow guides Farrend Austin and Johnny Keller behind their "sports"

By 1854, Milote Baker had established a second hotel in the village, as well as a store and the first local post office, all at the present intersection of Main and Pine Streets. In 1856, Saranac Lake was a settlement of fifteen families scattered throughout the area and "a headquarters for lumbermen, guides and tourists."1 Local stores supplied campers, outdoorsmen, and villagers with fresh produce and staple goods in exchange for furs, hides, venison, farm products, or cash. By 1868, Milote Baker employed thirty men as hunters and shipped as many as 500 deer each winter to markets.2

In I860, on the eve of the Civil War, Orlando Blood opened a third hotel in the Village of Saranac Lake on the shore of the millpond. The Adirondack resorts prospered throughout the war as men escaping the draft and those who had paid others to take their places on the battlefield retreated to the mountains. 3

After the war, a prospering middle class, increased leisure time, and improved access by railroad to Lake Champlain made this area even more accessible for tourists. A major impetus was the 1869 publication of the Reverend William H. H. Murray’s guidebook called Adventures in the Wilderness: or Camp-life in the Adirondacks. His fanciful descriptions of the pleasures of the Adirondacks, coupled with specific information about travel and lodging precipitated "Murray's Rush," also known as "the greatest invasion of the north woods ever witnessed by the resort hotels."4 Summer hotels like Martin's and Paul Smith's were enlarged and new ones were built throughout the region. Paul Smith's Hotel grew as the center and impetus for a wealthy and cultured seasonal community whose financial resources would greatly enrich the area. Later in the century, wealthy families would buy land and build their own elaborate summer "camps," like Knollwood Club, and others.

The summer visitors brought no permanent population increase to the area, but they created seasonal employment for local residents, and their presence stimulated improvements in transportation and modern conveniences.

Local residents earned extra money by working as wilderness guides and taxidermists. Near Martin's Hotel, a small colony of buildings was established at the end of Lake Street and on Algonquin Avenue to house the homes and shops of these men. Their work was by nature seasonal, and the earlier pattern of multiple sources of employment continued (as it does to the present time) with local farmers and other villagers finding a number of ways in which to earn cash income.

A guideboat at the Adirondack Museum Many used the long winter months to build guideboats, the indispensable vehicle for traversing the waterways of the wilderness. First developed between 1825-1835 in the Saranac/Raquette/Long Lakes area and evolving over the years by modifications to traditional craft, these lightweight rowboats held from two to four persons yet were light enough to be carried by one man from one lake to another over distances of up to four miles. Guideboat manufacture was a significant industry in the town of Harrietstown which included the village of Saranac Lake. In 1875 twenty-two of them were made of light pine at an expense of fifty to seventy-five dollars each. 5

A guideboat at the Adirondack Museum Many used the long winter months to build guideboats, the indispensable vehicle for traversing the waterways of the wilderness. First developed between 1825-1835 in the Saranac/Raquette/Long Lakes area and evolving over the years by modifications to traditional craft, these lightweight rowboats held from two to four persons yet were light enough to be carried by one man from one lake to another over distances of up to four miles. Guideboat manufacture was a significant industry in the town of Harrietstown which included the village of Saranac Lake. In 1875 twenty-two of them were made of light pine at an expense of fifty to seventy-five dollars each. 5

Footnotes

1. Alfred Lee Donaldson, A History of the Adirondacks (New York: Century Co., 1921), p, 227.

2. Frederick J. Seaver, Historical Sketches of Franklin and its Several Towns (Albany, NY: J.B. Lyon Co., 1918), p.374.

3. John J. Duquette,'"The Saranac Lake House," Adirondack Daily Enterprise, August 13, 1986.

4. Alfred Lee Donaldson. A history of the Adirondacks. Vols. I & II. (New York: Century Co., 1921). p. 196.

5. Town of Harrietstown, Census of 1875.