II. - In Pursuit of Health — The Rise of the Curing Industry (1860-1881)

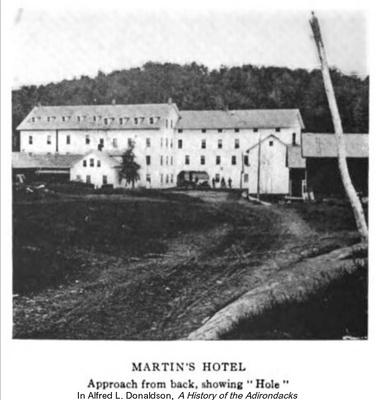

Among those who came to the Adirondacks in the mid-nineteenth century were people who came to the mountains in search of relief from illness. Reverend Murray wrote in 1869 about the dramatic recovery of a tubercular patient who entered the mountains an invalid and returned a healthy outdoorsman. Other books about the region mention the health-giving qualities of the climate, as much as fifteen years before Murray's book. As early as 1860 guests could be found at Martin's hotel who had come for the summer to recover from tuberculosis. In fact, a later guidebook was to call Martin's "a most desirable tarrying place for all in quest of health or sporting recreation."

The quest for health in the nineteenth century was more than the narcissistic self-improvement fads of modern times. For many, the search was a matter of life or death. The "White Plague" ran rampant for much of the century. The number of Americans infected with tuberculosis in the nineteenth century was as great as the combined number of cancer and heart disease patients today. By 1873 Tuberculosis, also called consumption, killed one out of every seven Americans in a slow but unalterable physical decline. 1 It was primarily a lung disease, but the tubercle bacillus could attack any part of the body. Once lodged, the infection spread unchecked, steadily wearing down the body's defense system, and eventually creating cavities in the lungs. At its more advanced stages the best-known symptoms were coughing, night sweats, paleness, weight loss, virulent sputum, and spitting up blood. There was no known cure.

Transferred by airborne bacilli, the disease spread rapidly in enclosed or crowded environments, threatening immediate family members as well as neighbors. Slum dwellers and struggling factory workers were especially vulnerable, as were the very rich, paradoxically, who employed servants from poor living conditions who unknowingly harbored the disease. The disease did not confine itself to the very old and the very young, but instead most frequently struck people in the prime of their life. 2

In its sheltered position in a deep basin of hills, the village of Saranac Lake had begun to attract invalids as early as 1860 with the opening of Martin's Hotel. Until the 1870s, however, none of these patients seemed to have braved the frigid winters of the Adirondacks. The first tubercular patient credited with staying year-round in Saranac Lake was Mr. Edward C. Edgar who spent the winter of 1874 at the boarding house run by the wife of Lucius Evans, a well-known local guide. At this time, the village of Saranac Lake was little more than a saw mill, a small hotel for guides and lumbermen, a schoolhouse and perhaps a dozen guides' houses scattered over an area of an eighth of a mile. 3

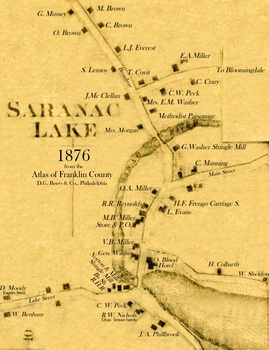

Another contemporary description mentions 50-60 log houses in town. The population numbered about four hundred, and there were no newspapers, no lawyers and no churches. The nearest train station was in AuSable Forks, 42 miles away, but the stagecoaches ran regularly and a telegraph connected the village with the rest of the world. [Map #2]

Up to this time, Saranac Lake was similar to many other hamlets within the Adirondacks. The person who almost single-handedly altered this pattern of development was Dr. Edward L. Trudeau, who arrived in the village in 1876.

Edward Livingston Trudeau was born in New York City in 1848. His father was a doctor from New Orleans and his mother was French. Men in his mother's family had been physicians in France almost as far back as the family lines could be traced. His parents divorced when Edward was young, and he spent much of his childhood in France, returning to New York with his grandparents at the end of the Civil War.

Trudeau was friendly with and related to some of America ' s wealthiest and most prominent families, including the Aspinwalls and the Livingstons, and he led the carefree life of a dilettante on his return to the States, finally enrolling in the Naval Academy in 1865. A major turning point came that fall when Edward's older brother Francis contracted a very virulent and rapidly progressing form of tuberculosis. Edward, seventeen years old, left school to nurse his brother full-time for three months. Francis died two days before Christmas, 1865. Edward later wrote in his autobiography:

"This was my introduction to tuberculosis and to death. It was my first great sorrow — and I have never ceased to feel its influence. In after years it developed in me an unquenchable sympathy for all tuberculosis patients.4

For the next three years, Trudeau continued his rounds as one of the "smart social set" in New York City. Some of his interests were hunting and fishing, having inherited an enthusiasm for the wilderness from his father, who was a close friend of naturalist John J. Audubon. Sometime in this period, most likely through his friends, the Livingstons, he apparently got to know Paul Smith, whose hotel was quite famous with New York City sportsmen, and he made his first trip to the Adirondacks. 5 After dabbling in the navy and brokerage firms as potential careers, Trudeau enrolled in the College of Physicians and Surgeons in New York (now part of Columbia University), graduating in 1871. He married Charlotte Beare, daughter of a clergyman, in the same year. Trudeau began a private practice, first in Little Neck, Long Island (his wife's hometown), then moving into New York City where he was soon deeply involved with a private practice, clinics and classes in Manhattan.

Soon after the move, at the age of 25, Trudeau learned that he had contracted tuberculosis. The prescribed winter in Aiken, South Carolina did not help his symptoms, and his condition continued to decline. In the summer of 1873, a week after the birth of his second child, Trudeau returned to Paul Smith's Hotel as an invalid to spend his last days in the woods he loved so well. Leaving his young family, he said he was drawn "by my love for the great forest and the wildlife, and not at all because I thought the climate would be beneficial in any way." He arrived too weak to walk and yet after three months in the Adirondacks, he had improved enough to return to New York City with "the appearance of a man in good health." 6

Winter brought a relapse unrelieved by a move to St. Paul, Minnesota. He returned to Paul Smith's the following spring and summer. At the advice of Dr. Alfred L. Loomis, Professor of Medicine at New York University and himself a tuberculosis patient, Trudeau stayed on through the winter of 1874-75 with Paul Smith and his family. His symptoms continued to improve and the Trudeaus remained at Paul Smith's through the following summer.

When Paul Smith moved to Plattsburgh the following winter, Trudeau had to find another place to stay with his family. Unable to find suitable lodgings in Bloomingdale (a larger village at the time), he continued along the highway to Saranac Lake. Here he and his family rented the Reuben Reynolds house on Main Street. For the next six years, they boarded at Mrs. Lute Evans' house on Main Street, a place already "famous as a homelike and exclusive stopping place for sportsmen and invalids." 7

Doctor Trudeau attempted several times to move back to New York City, but each trip ended in a relapse. Hoping for a permanent cure that would allow them to return to the city, the family rented a winter place in the village for seven years, until finally building their own house in 1883 on the corner of Church and Main Streets. They continued to spend their summers in camp at Paul Smith's.

Until 1880, Trudeau hunted and fished in the woods as he was physically able. As he continued to recover, he slowly began to resume his medical practice. His personal physician, Dr. Loomis in New York City, began to refer patients to Saranac Lake to stay in the mountains under Dr. Trudeau's supervision. The presence of a doctor in residence was a benefit few other settlements in the Adirondacks shared, and it was a key factor in the development of the village as a health resort.

In 1875, the Berkeley House was built in Saranac Lake "for the accommodation of the city TB patients who were then beginning to seek the locality as a health resort, but for whose care there were neither suitable cottages nor hotels.8 Though having a capacity for only 15 or 20 guests, it was of ample size for all the demands then made upon it." 9 Milo Miller later described the Berkeley as "the first public house for the reception of invalids in the Adirondack mountains. " The building stood in the heart of the Berkeley Square Historic District until a fire destroyed it in 1981.

In the summer months, Dr. Trudeau would come down from his camp at Paul Smith's twice a week to see patients. He soon had quite a following.

"It was not long before the number would often be so large that they thronged his office porch and yard. The village had no suitable or adequate accommodation for them for a time, but with the building of the Berkeley and the enlargement or erection of houses and cottages expressly to care for invalids, provision was eventually made for all. By 1882 visitors had become so numerous, including many who could pay only a very moderate charge for care and treatment, that Dr. Trudeau determined, if funds could be raised, to establish a sanatorium for incipient cases at which charges should be less than actual cost." 10

In the summer of 1883, Trudeau suggested the idea of a semi-charitable sanitarium for the study and cure of tuberculosis to Anson Phelps Stokes, a New York banker who summered nearby at Upper St. Regis Lake. Stokes immediately contributed five hundred dollars to Trudeau's proposal. The St. Regis camp owners and their friends vacationing at Paul Smiths became the backbone of financial support for the Adirondack Cottage Sanitarium. Dr. Loomis and other prominent doctors offered their professional support. Local guides and residents chipped in to buy sixteen acres of a sheltered hillside overlooking the valley and donated the land to Trudeau's new project.

Trudeau modeled his fledgling institution on one founded in Goebersdorf, Germany, in 1852 by Dr. Hermann Brehmer, who advocated a climatological treatment for tuberculosis, bringing patients to higher mountain altitudes where the combination of fresh air, exercise, ample rest, and good food could effect their cure. By 1884, only a handful of sanitoria were available for health seekers — and all of them were in Europe. Trudeau opened his Adirondack Cottage Sanitarium in February 1885 with the completion of an administration building and three small cottages, including Little Red," a one-room cottage with a small porch. Trudeau's first two paying patients, Alice and Mary Hunt, sisters who worked in a New York City factory, occupied "Little Red," a one-room cottage with a small porch.

For most of the nineteenth century, the term "sanitarium" was applied to all chronic care institutions. Coming from the Latin word ‘’sanitas’’, meaning health, its most common meaning is "health resort." Today it is most commonly the designation for mental health institutions because of its close etymological links with the word "sanity." By the early 1900s, however, a place for the treatment of invalids, particularly consumptives, was more often called a "sanatorium," from the Latin word ‘’sanare’’, which means to cure or heal. Trudeau christened his institution the Adirondack Cottage Sanitarium in 1885. After his death, it was renamed the Trudeau Sanatorium.

Trudeau's establishment was the first successful sanatorium in America for the treatment of tuberculosis. The American Mountain Sanitarium for Pulmonary Diseases, opened in 1875 by Joseph W. Gleitsmann in Asheville, North Carolina, lacked major financial backing and had been forced to close after only three years. Trudeau's close ties with wealthy families vacationing at Paul Smith's assured that the Adirondack Cottage Sanitarium did not meet a similar end. Individual donations and annual charity events consistently raised the money necessary to maintain the institution. Wealthy benefactors seemed more likely to underwrite the cost of a small cottage as their own individual gift rather than contribute towards a large institutional building, and (though tuberculosis was not yet known to be a communicable disease) Trudeau believed that aggregation should be avoided and more fresh air would be available in separate units.

Even as he opened the Adirondack Cottage Sanitarium, Dr. Trudeau began to seriously study the disease of tuberculosis. At Christmas 1883, his friend, C. M. Lea, a Philadelphia medical publisher, gave him a complete hand-written English translation of a scientific paper, "The Etiology of Tuberculosis," written by Robert Koch in Germany the previous year. Its contents were a revelation for Trudeau and the world. Koch had discovered the tubercle bacillus, the bacterium that caused tuberculosis, and he showed that it could be identified under a microscope.

Fascinated by this radical new discovery and the potential which it brought of finally being able to identify both the cause and — with luck — the cure of tuberculosis, Trudeau attempted to replicate Koch's experiments. He returned to New York City that winter to learn how to stain and recognize the tubercle bacillus under the microscope. In 1885, Trudeau grew tubercle bacilli in artificial culture in Saranac Lake, the first scientist in America to do so. His makeshift home laboratory was the beginning of the Saranac Laboratory for the Study of Tuberculosis, Trudeau's second major institutional innovation, and the first scientific research laboratory in the united States devoted primarily to tuberculosis-related research. The Saranac Laboratory on Church Street, built in 1894, was the first lab in the United States designed for and devoted exclusively to tuberculosis research.

Trudeau's genius was his openness to ideas, applying and re-applying the newest in scientific thought to the pragmatic successes he had found in folk medicine, until he found explanations that made sense of his solutions. His European education and access to ideas through both the money and the connections of his wealthy and cultured friends were an unusual resource which he generously brought to bear on the problem of tuberculosis. Isolated as he was, he was also quite free to ponder new ideas, entirely unfettered by the politics of association with peers. the independence of his thought and his unrelenting determination were important qualities in the success of his research.

In his lifetime Dr. Trudeau was to receive a number of awards, including the first presidency of the National Association for Study and Prevention of Tuberculosis, honorary American president of the International Tuberculosis Congress, and the prestigious title of President of the Congress of American Physicians and Surgeons. At his death in 1915, the Adirondack Cottage Sanitarium was renamed the Trudeau Sanatorium in his honor.

In the summer of 1886, Dr. Trudeau devised a simple experiment which demonstrated the beneficial effects of climate, fresh air and ample food on the course of tuberculosis in infected animals. He infected a number of rabbits with the tubercle bacillus and then confined half of the infected animals, along with a control group of healthy rabbits, giving them a minimum of food, sunlight, fresh air and exercise. The rest of the infected rabbits were set free on a little island (now called Rabbit Island) in Spitfire Lake near Trudeau's camp. Here they ran wild in the open air with plenty of food and water.

After a period of time he examined the animals. The infected rabbits that were confined all developed tuberculosis and died, yet the healthy ones merely failed to thrive in confinement; they did not come down with TB. On the island, however, all of the rabbits thrived, despite their infection.

The results provided the proof which Dr. Trudeau had sought. First was the conclusion that bad conditions in and of themselves could not produce tuberculosis. His second and more far-reaching conclusion was that in the presence of tuberculosis infection, a subject's resistance could be directly affected by the environment. Fresh air, good food, ample rest, and moderate exercise could actually slow down or stop the progression of tuberculosis. Dr. Trudeau published the results of his experiment in July 1887 in the American Journal of the Medical Sciences and read a paper on the subject at a national meeting of the American Climatological Association that same year.

Trudeau's work was followed with great interest by the medical world, and his initial successes with patients were welcome beacons of hope for victims of the disease which had no cure. Popular literature extolled the health-giving virtues of the mountains, inspiring ever larger numbers to come to the Adirondacks. A handful of doctors regularly referred patients to Dr. Trudeau's care, and the number of health-seekers arriving in Saranac Lake steadily rose. However, the name of Saranac Lake first became nationally recognized as a health center in the winter of 1887-1888 when the Scottish author Robert Louis Stevenson came to the village to cure.

The Stevenson Cottage Recently catapulted to fame as author of The Strange Case of Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde, Stevenson came to America in 1887 in search of a better climate for his lung ailments. (Although it was never proved, Dr. Trudeau suspected he had an arrested case of tuberculosis.) Stevenson arrived in New York in September, too ill to continue to Colorado as originally planned. Local doctors recommended a winter in Saranac Lake instead, so Stevenson and his family rented quarters in the house of local guide Andrew Baker. Stevenson became Trudeau's patient and friend, and his health steadily improved throughout the winter. To Trudeau's despair, Stevenson's self-prescribed cure regime included chain-smoking cigarettes, writing in bed in a tightly sealed-up room, pacing on the rambling open veranda of the Baker cottage, and ice-skating on Moody Pond. Stevenson remained in Saranac Lake for about six months, leaving in mid-April for the South Pacific where he spent the rest of his life. The Baker Cottage (now called the Stevenson Cottage) still stands, a museum devoted to the author's life and works with the largest collection of Stevensonia in America, as well as headquarters for the Stevenson Society.

The Stevenson Cottage Recently catapulted to fame as author of The Strange Case of Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde, Stevenson came to America in 1887 in search of a better climate for his lung ailments. (Although it was never proved, Dr. Trudeau suspected he had an arrested case of tuberculosis.) Stevenson arrived in New York in September, too ill to continue to Colorado as originally planned. Local doctors recommended a winter in Saranac Lake instead, so Stevenson and his family rented quarters in the house of local guide Andrew Baker. Stevenson became Trudeau's patient and friend, and his health steadily improved throughout the winter. To Trudeau's despair, Stevenson's self-prescribed cure regime included chain-smoking cigarettes, writing in bed in a tightly sealed-up room, pacing on the rambling open veranda of the Baker cottage, and ice-skating on Moody Pond. Stevenson remained in Saranac Lake for about six months, leaving in mid-April for the South Pacific where he spent the rest of his life. The Baker Cottage (now called the Stevenson Cottage) still stands, a museum devoted to the author's life and works with the largest collection of Stevensonia in America, as well as headquarters for the Stevenson Society.

In this earliest phase of tuberculosis curing, invalids coming to the mountains stayed in hotels or in local homes with no special architectural arrangements to distinguish these buildings from any other houses. The rent-paying boarder usually had his/her own room and ate meals with the family, or, if bedridden, had meals brought to their bedside. Others, like Stevenson, rented larger quarters with kitchen privileges. The houses were typical mid-nineteenth century vernacular residences, often Queen Anne in style with porches or verandas primarily used by summer visitors. While these porches became important gathering places for curing patients, they had no special adaptations or features that would distinguish them from other porches typical of the time period and style.

Saranac Lake's Union Depot The management of a consumptive's cure was quite informal. The patient was enjoined to be outdoors as much as possible and encouraged to be active without overdoing it. Trudeau himself hunted and fished while curing, even though at times he was too weak to leave his guideboat and had to be carried from his hotel. A visitor in 1888 wrote of "consumptives in bright caps and many-hued woolens gaily tobogganing at forty below zero." 11

Saranac Lake's Union Depot The management of a consumptive's cure was quite informal. The patient was enjoined to be outdoors as much as possible and encouraged to be active without overdoing it. Trudeau himself hunted and fished while curing, even though at times he was too weak to leave his guideboat and had to be carried from his hotel. A visitor in 1888 wrote of "consumptives in bright caps and many-hued woolens gaily tobogganing at forty below zero." 11

Railroad passenger service to the village of Saranac Lake was completed during Stevenson's six-month visit, considerably improving accessibility. No longer did a journey to Saranac Lake include the lengthy forty-plus miles of rough roads from Ausable Forks. Now trains from Plattsburgh could bring visitors and patients directly to the heart of the village. The easy rail access, resident physicians, and the publicity which Stevenson's visit generated for the nascent health resort set the stage for an explosion of growth in the following years.

Footnotes

1. Philip L. Gallos, Cure Cottages of Saranac Lake; Architecture and History of a Pioneer Health Resort. Saranac Lake, NY: Historic Saranac Lake, 1985, p. 2. The original source for the "one in seven people" figure is Robert Koch, in a lecture given on the evening of March 24, 1882, in which he described his discovery of Mycobacterium tuberculosis, the bacterium that causes tuberculosis. See Robert Koch and Tuberculosis at NobelPrize.org

2. Ibid., p.25.

3. Frederick J. Seaver, Historical Sketches of Franklin County and its Several Towns. Albany, NY: J.B. Lyon Co., 1918, p. 374.

4. Edward L. Trudeau, An Autobiography. (Garden City, NY: Doubleday, Doran & Company, Inc., 1915, reprint 1934)

5. Edith H. Shepherd, "Trudeau, The Beloved Physician," The Long Island Forum. February 1984, p.24.

6. Edward L. Trudeau, An Autobiography.

7. Donaldson, p. 232.

8. Per Phillip L. Gallos. However, the Registration Form for the National Register of Historic Places gives the year as 1876. Frederick Seaver gives the date as 1977.

9. Seaver, p.376.

10. Seaver, p.381.

11. Gallos, p.34.