Etymology

The term 'Mescalitan' derives from 'Mescalititlan' which the Spanish soldiers on the Portola Expedition named the island after Mescaltitlan lagoon in Nayarit, Mexico. The colonizers were said to be reminded of the populated, bountiful and thriving villages of this similar lagoon. The term has Nahuatl origins and refers to the Aztec heartland, where mother earth is said to reside on an island in a lagoon. (Gamble p. 18)

Sketch of the land grant Daniel Hill received in 1846 depicting Goleta, CA

Sketch of the land grant Daniel Hill received in 1846 depicting Goleta, CA

Location

At the time of European contact, the coastal region from Carpentaria to Goleta in California consisted of several large estuary systems. The Goleta lagoon was the largest of these estuaries and was surrounded by densely populated Chumash towns.

This lagoon, which is the modern day Goleta Slough, surrounded an island atop which the Chumash village of Helo was established. The area was valued for its defensive location, as Chumash warfare in the channel was persistent.

The lagoon was up to eleven feet deep and separated from open sea by a sandspit; an expanse of sandy beaches bordered by kelp beds which then gave way to the ocean. The island within the lagoon rose 21 meters above the slough and had a circumference of less than a kilometer. The island had two springs, on the eastern and northwest edge. The island contained scattered oaks, grassland, and vernal pools at the time of Chumash inhabitation and first European contact. The earliest known maps of the area were drawn by Pantoja in 1782

This island, named Mescaltitlan by the Spanish colonizers on the Portola expedition, had the greatest amount of Chumash midden deposits in the Santa Barbara region (Gamble p. 19).

http://goletahistory.com/mescaltitlan-island/

http://goletahistory.com/mescaltitlan-island/

History

Chumash inhabitation in the Santa Barbara Channel dates back from between 7 and 9,000 years ago and represent the first populations of H. sapien in California as well as North America. Estimations of the development of complexity are around 4,500 years ago.

First European contact dates to the journey of Portuguese Juan Rodriguez Cabrillo in 1542. The diary of this expedition has not survived, but additional documentation of this journey was written by Juan Leon, a Mexico City notary who had read the expedition accounts and interviewed the surviving explorers. The accounts describe a female Chumash chief, villages, houses, and plank canoes. Juan Rodriguez Cabrillo and the expedition traveled as far as Monterey Bay before returning and spending a winter on San Miguel Island due to unfavorable weather conditions for maritime travel. He contracted gangrene and was reportedly buried on the island.

After this first journey, the Spanish conquests shifted to searching for inland trade routes and eventually to efforts to establish ports on California’s coast that could facilitate voyages from Manilla , Phillipines to Acapulco, Mexico. Documentation around the Goleta Slough area is nonexistent until the first land expedition to California, the Portola expedition in 1769. Juan Crespi was a priest appointed the record keeper as the expedition made its way along the California coast from San Diego to San Francisco Bay.

Crespi estimated 800 people inhabited the island in 1769, and documented several aspects of Chumash life, specifically the degree to which Helo had more people, homes, canoes, and bounty than other encountered villages along the coast. Goycoecha is said to have taken a census in 1796 of 101 people remaining on the island.

A sketch of the Island from 1929 http://goletahistory.com/mescaltitlan-island/

A sketch of the Island from 1929 http://goletahistory.com/mescaltitlan-island/

A multitude of factors might have contributed to this rapid depletion in population at Helo. Chumash conflict was suppressed due to the presidio military installation in 1782 and 1786, leaving the defensive village location no longer valuable. Drought and elevated sea surface tempuratures might have encouraged the Chumash peoples to be more willing to move to missions, because the changing climate reduced the availability of their food sources. Between 1787-1834 the elevated sea surface temperatures degraded productivity of kelp beds and damaged fish and sea mammals. Sanitation problems as with an increasing population have also been suggested as a possible cause.

Warm waters could have also functioned to bring yellow tail and tuna to fishing areas and could shift subsistence patterns. Overall, this diversification of subsistence in response to a changing landscape is exemplary of Chumash life.

However, by 1804 the village of Helo was abandoned. Santa Barbara Mission records indicate 152 baptisms from Helo around this time, which was also marked by the agricultural intensification of the Spanish colonies. By 1811, the area was covered with fields of wheat and livestock roaming. These changes further restricted the ability of the Chumash to rely on plant foods and the productivity of the land (Gamble p. 34).

The Goleta Slough, once a lagoon, was gradually filled with sediment because of the erosion typical of such agriculture. In 1860 the slough was completely filled.

1928 Aerial of the Goleta Slough Area http://goletahistory.com/mescaltitlan-island/

1928 Aerial of the Goleta Slough Area http://goletahistory.com/mescaltitlan-island/

The remaining history of Mescalitan Island is marked by archaeological excavations and development. H. C. Yarrow’s excavations of 1875, which revealed early insight into Chumash life. The artifacts of Olson’s 1930 excavations are housed at Phoebe Hearst Museum at Berkeley.

Decades of ditching, diking and filling continued to reduce the Slough’s size and productivity. In 1941, construction began on the Marine Corps Air Station, later to become the Santa Barbara Municipal airport. Over 400 acres of salt marsh were filled in. Since then, runways have been extended, more roads have been built, creeks have been channelized or relocated, and beach facilities have been developed. Most of Mescalitan Island was bulldozed to create fill for the construction of Ward Memorial Boulevard. Today, only about 430 acres remain of the Slough’s original 1150 acres. Mescalitan Island, once a large, thriving Chumash settlement, is now merely a small hill located near the intersection of Sandspit Road and Moffett Place with junk scattered around its base. In the last 20 years alone, at least 18 species of birds, reptiles, amphibians and mammals have disappeared from the Slough. Many areas are slowly dying because of severely decreased tidal circulation. The Goleta Slough is a local treasure. The largest estuary between Point Mugu and Morro Bay, the Goleta Slough has been described as “the major environmentally sensitive habitat area in the Goleta Valley’s Coastal Zone.”In the 1970s the Goleta Sanitation District began plans to expand into the Helo village sight, which was largely undisturbed prior to 1987. The findings of this more recent excavations form the basis for the next section on Chumash modes of livelihood and environmental interaction as detailed from first person interviews with Lynn Gamble, an expert on the area whose archaelogical research is detailed in her publication The Chumash World at European contact: power, trade, and feasting among complex hunter-gatherers.

Edit conflict! Other version:

Today

Mescalitan Island is now the location of the Goleta Sanitary Sewage Treatment Plant

Aerial view of the Goleta Sanitary Sewage Treatment Plant, which serves IV, with the remains of Mescalitan Island at left and UCSB in the distance.

Aerial view of the Goleta Sanitary Sewage Treatment Plant, which serves IV, with the remains of Mescalitan Island at left and UCSB in the distance.

Chumash

Edit conflict! Your version:

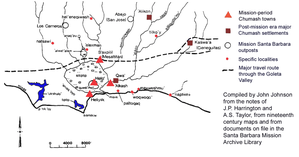

Complied by John Johnson from the notes of J.P. Harringtion and A.S Taylor from 19th century maps

Complied by John Johnson from the notes of J.P. Harringtion and A.S Taylor from 19th century maps

Chumash Use of Mescaltitlan Island

Crespi described in 1769 that the village of Helo was full of bonitos, large sardines, needlefish, “…barbecued fish piled high on rooftops, brought us dried fish while women inside homes grinded gruel, toasting seeds, making baskets with such patterns and pictures as to strike one with wonder.” (Gamble p. 18).

Burials accompanied by steatite, bone and shell beads and ornaments, flaked points and blades, well made steatite and sandstone bowls, stone pipes, bone implements found in formal cemetaries. An unusual discovery was made of a female burial lying flexed upon a whale’s scapula ornamented with inlaid beads set in asphaltum mastic.

Clay floors, roof fall, storage pits, and trash deposits were all unearthed and found to be typical of the village houses at this time.The houses were clustered and built in rows along the streets between them. Settlers wrote ‘homes are more crowded and much larger than anything northward” (Gamble p. 114) As roughness of sea prevents seeking food during this time, smaller houses next to the main house were built for food storage in winter. These pantries stored fish and grains, after they had been dried in storage granaries; which were woven containers elevated on poles.

Cabrillo detailed in their towns they had specialized structures such as large plazas and circular enclosures that they danced inside of, childbirth huts, ‘male puberty huts’, windbreaks, sweat lodges, as well as playing field areas with low walls. Every fireplace was said to be a place of honor where families would gather.

,

Chumash Environmental Management

The Chumash employed controlled burns that functioned to reduce shrubs and increase the desirable grasses and bubs used for food and materials. An overall increase in chaparral since European contact suggests less burning, which was normally done by the Chumash after seeds were harvested in late summer. Red Maid and Chia seeds are said to only be obtainable through the use of controlled burns. Attraction of deer to recently burned patches where new growth appeared looks to have led to an increase in terrestrial hunting, however, deer were perhaps more valued for their bone ideal for tool making than for flesh (Gamble p. 165). It is unclear if this element was intentional, but it is well established that the Chumash engaged in horticultural techniques such as leaving plants behind to ensure future productivity, pruning, tilling, weeding, coppicing, and burning. The Chumash taboos that discouraged overexploitation are also seen as a form of environmental management (Gamble p.33).

Mechanisms such as storage, exchange, currencies, environmental modifications came about in Chumash life as adaptive strategy to minimize the risk and livelihood damage associated with cyclical droughts. These events became more challenging with population growth (Gamble p.34-6).

Subsistence Botany

The Chumash depended on plants common in fresh and saltwater marshes that once surrounded the area. The modern losses of these ecosystems have implications for the loss of subsistence potential in the Goleta slough, and display how the landscape has evolved over time, as shaped by human interaction.

Examples of the various plants are:

- Goosefoot and pigweed family of plants - seeds and greens

- Elderberry, Salvia sage, Rred maids, Yucca whipplei, Saltbush, Seashore Blite, Native Barley - Medicinal and food use

- Salt Marsh and Pickleweed were shown to be dominant in a reconstruction of the landscape in 1750-90 by David Stone.

Edible plants and uses:

- Amaranthus Amaranth – seeds and leaves

- Atriplex Saltbush seeds

- Chenopodium Pigweed seeds

- Suaeda Blite hair/basket dye

- Distichlis spicata Salt grass, plants beaten to remove surface encrustations for use as salt

- Hordeum Barley seeds

- Phalaris Canaray grass seeds

- Cruciferae Mustard seeds leaves

- Cucurbitaceae wild cucumber

- Juniperus Juniper

- Montia portulaceae Miners lettuce

- Solanaceae solanum Nightshade

- Umbelliferae parsley carrot

- Urticaceae nettle (Gamble p.169-72).

- Juncus, Sumac, Rhus trilobata, Scirpus sp Bulrush roots, grass stems of Epicampas regins, and Tule rush Scirpus lacustris used for basket making.

- Wild alfalfa, Fern and Carrizo used for housemaking, roofs particularly (Gamble p.29).

Common Minerals

Asphaltum, bitumen, or tar glue was used as a fixative, sealant for plugging holes, in plank canoe construction, and often mixed with pine pitch. Monterey chert was used for crafting flaked point tools.

Fish

- Embiotocidae - Northern Anchovy. Squalus acanthias - Piny Dogfish. Sardinops sagax - Pacific Sardine. Sarda chiliensis - Pacific Bonito. Rhinobatos productus - Shovelnose guitarfish. Paralichthys californica - California halibut.

- Shellfish

- Chinoe spp. California venus

- Saxidomus nuttallii Washington clam

- Tagelus californianus Jackknife clam

- Ostrea lurida California oyster

- Protothaca Littleneck clam

- Hinnites multirugosus Giant Rock Scallop

- Tivela stultorum Pismo clam

- Mytilus Mussels

- Haliotis Abalone (Gamble p. 27-28).

Sources

Gamble, Lynn H. The Chumash World at European contact: power, trade, and feasting among complex hunter-gatherers. Univ of California Press, 2008.