Sun sets into Central Bank building, fall equinox 2016

September 23, 2018, shot with eclipse filter

Astonishingly, Oakland is in a category with the Pyramids and Stonehenge: it has an equinox observatory built into the skyline – though it is under imminent threat from developers.

On equinox days (September 22-23 and March 19-20), the sun settles into the side of the Central Bank Building at 14th and Broadway, when viewed from directly east on the far shore of Lake Merritt (Lakeshore Ave. for about 200 feet south of Brooklyn Ave.).

Central Bank with temple design and hexagonal minaret

This equinox-marking feature is no coincidence. In 1925, when the Central Bank building was raised from a five-story cube to an imposing 16-story temple – complete with minaret – the bank’s VP Robert M. Fitzgerald (an Oakland High alum) and president Joseph F. Carlston were implementing a vision of the bank’s founder, Volney D. Moody, and its fourth president and Fitzgerald’s father-in-law, Thomas Crellin.

Volney D. Moody, 1829-1901

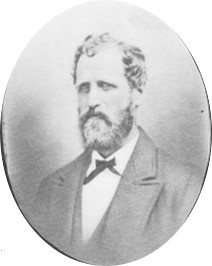

Thomas Crellin, 1833-1908

Moody and Crellin were interested in geometry and solar astronomy; and going by their private real estate purchases (see attached diagram), they seem to have been planning some kind of sun-aligned monument. From 1876 through 1901, these two Oakland pioneers accumulated eleven properties in line with the solstice or equinox sunrises or sunsets when viewed from a succession of four vantage points relevant to Volney Moody. The four points are the First National Bank of Oakland, the old Masonic Temple, a Moody property later to become the Tribune Tower, and the Central Bank building itself.

What sparked Moody’s and Crellin’s interest in solar astronomy and architecture is likely Freemasonry, an affiliation they shared with the builders of the other three towers that went up in the same vicinity in the 1910s and 1920s. Frank Mott built the new City Hall in 1915, whereas Joseph R. Knowland built the Tribune Tower and William Garthwaite built the Oakland Bank of Savings Tower in 1924. All of them were Masons.

The four towers cast evening shadows that swept back and forth across Lake Merritt over the course of the year. People standing along the lake shore would see the sun set into the sides of the buildings on the winter solstice at the spot where Children’s Fairyland is, on equinoxes at locations from Hanover Avenue to the Cleveland Cascade, and on the summer solstice near the outlet of the lake at 12th Street. The only buildings between 14th Street, Franklin and Lake Merritt that were taller than nine stories, the Women's City Club, the Hill-Castle Apartments and the Bechtel Building, were safely clear of the sunrise-view and sunset-shadow lines of all four of these buildings on equinoxes as well as solstices.

Most of those sunset-shadows are obscured now due to the Smith Department Store building (1956) and a downtown construction wave in the 1970s. But the view from Lake Shore Avenue of the equinox sun setting into the Central Bank has been preserved, due to the position of shorter historic buildings nearby, like the Athenian-Nile Club and the Everis Building. The Everis Building was built on land that Fitzgerald and Carlston acquired from the First Presbyterian Church in 1912.

Likewise preserving the equinox line from the Central Bank, Volney Moody’s first property on Harrison (see diagram) became the site of a one-story garage (1600 Harrison).

This not-very-stately building has its own remarkable part to play in this larger story. When it was built in 1921, the owner of the adjacent property to the south sued in McKean v. Alliance Land Co., claiming a one-foot encroachment onto his lot. (Alliance Land Co. was a d.b.a. for Volney Moody’s first wife Adaline Wright, her daughters, and her then husband Henry Hubbard. She had inherited from her son who died in 1910.) McKean wanted the building abated. Robert M. Fitzgerald, who was a very prominent lawyer and former president of the state bar, successfully defended against this suit all the way to the California Supreme Court. It was determined based on a survey that the building had encroached by just short of one inch, and the aggrieved plaintiff was awarded $10 for his trouble. In fact, if you take out a tape measure, the plaintiff’s property is found to be one foot shorter than it should be according to the block books, whereas the property adjacent to the Moody property on the north, which was bought by the Central Bank in 1921, is now about a foot wider than it was credited to be on the books at the time. The Moody property was thus effectively shifted one foot to the south – certainly to ensure that at least the southeast corner of the garage building was in the equinox line from the Central Bank. One hopes that McKean, who had just bought the property that year, was at least made whole monetarily after the fact.

Robert M. Fitzgerald, 1858-1934

Laura Crellin Fitzgerald,

1875-1970

Other properties that protected the equinox and solstice sight lines were also bought in the late 1910s and early 1920s and developed by society women who knew Robert and Laura (Crellin) Fitzgerald, like Miss Helen M. Dille (330 15th St., 363 15th St., 314 14th St. and 1750 Webster), Frances C. Kehrlein (1425 Webster and 150 17th St., i.e. the Tudor Hall Apts.), Kate Palmanteer, widow of the bank’s short-lived fifth president (322-24 14th St.), Edith Haddon (1800 Madison, i.e. the Lake Merritt Hotel), Etta H. Merritt (1528 Alice) and Ida E. Hill, a founder of the Women's City Club. Mrs. Hill bought Thomas Crellin’s old property at 1561 Jackson that he had given to his nephew T.A. Crellin, and by 1928, the Hillsonia Hotel was listed at that address in Polk’s Oakland City Directory.

Harry and Anne Kreiger, partners in the Hill-Castle Apartments just north of the bank's summer solstice view line, also bought the lot at 1523 Harrison. It is now a parking lot and is currently targeted as a possible highrise.

In a 1920s atmosphere of rising and virulent racism and anti-Semitism, the equinox project was also supported by Jewish contributors who bought properties in the equinox line, like Walter Arnstein, builder of the Benicia-Martinez railroad bridge (who bought 359 15th St), Max Levy (1546 Alice) and Louis Scheeline, owner of the tailor shop in the Athenian-Nile Club building (who bought and remodeled 416 14th St).

Symbol on Central Bank building

Perhaps in acknowledgement of this participation and as a statement of defiance against the growing strength of the KKK in Oakland in the twenties,1 the Central Bank’s top-floor window arches have a symbol that looks like a combination of a Star of David and a Catholic three-ring trinity symbol. Fitzgerald himself was Roman Catholic.

Sadly, Helen M. Dille ran into some financial difficulties in the Great Depression and was unable to develop her properties along 15th Street in the grand style of the Tudor Hall Apts or the Lake Merritt Hotel. And unfortunately, the Central Bank failed in the Depression and was taken over by the Bank of America, so Fitzgerald and Carlston were no longer in a position to help her acquire more land and build anything imposing there. She did manage to put up three charming two-story buildings at 363 15TH Street, 330 15th St. and 314 14th Street. The latter two are contributors to the Harrison & 15th Streets Historic District (the first for some reason is not, though just as nice as the others).

Walter Arnstein’s property at 359 15th came into the hands of Stephen Herrick, the owner of Herrick Iron Works, who hired prominent local architects Miller and Warnecke to build a one-story commercial building in 1938 that was used as a diner for a long time. This building was remodeled in the 1950s, but is currently targeted for demolition for the proposed highrise project at 1433 Webster.

Along the equinox line at 15th and Webster

On the other side of the lake, the Edgemere Manor apartment building at 2122 Lake Shore Ave was built in 1929, and situated to catch the shadow of the Central Bank on the equinox. It has a broad, bright front, perfect for displaying the shadow of the downtown building and its little turret. And on the top floor, the façade features four suns, for the four seasons, and three mustachioed faces looking in the directions of the summer solstice, equinox and winter solstice sunsets over the lake.

2122 Lake Shore Avenue -- ever watchful

The lot for 2122 Lakeshore was assembled in the 1910s by purchases from three different property owners by Frank Flint Porter. He was the founder of a Masonic lodge and namesake of the Porter Building, an office building on 15th Street on the same block as the Central Bank. Also in the 1910s, Porter was buying up property in the winter solstice sunset line (viewed from the Central Bank) on the same block near 2nd and Castro where Volney Moody had bought a big parcel in the late 1870s (see diagram above). Meanwhile, the iron work for 2122 Lakeshore was provided by Herrick Iron Works,2 the same company that later owned and built a small building at 359 15th Street, in the equinox line from the Central Bank. That building still stands, though in a remodeled condition, and is targeted for demolition.

Without a major building in the equinox line, like the YWCA building across the street, the 15th Street corridor has remained vulnerable to redevelopment that would ruin the equinox observatory. At some point an 85-foot height limit was enacted along 15th Street, which protects the view. But two proposed developments are seeking exemptions from the height limit at 1433 Webster and 1510 Webster. These proposed buildings, and one other outside the 85-foot height zone, would completely obstruct the equinox sunset view.

Although the skyline gap between the Central Bank and the Smith Department Store building was finally filled in just this summer by the building under construction at 601 12th Street, the new building has a see-through design where it counts. So, though we won’t see the sky there anymore on any ordinary day, we will see the sun descend through the new building’s transparent floors on the equinox – that is, unless one of these proposed projects gets a permit to block the view.

Links and References

1. Chris Rhomberg, No There There: Race, Class and Political Community in Oakland (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2004), pp. 50-72.

2. "Construction Started on New Apartments," Oakland Tribune, August 5, 1928, p. M-3.

(The main primary sources for this page are the tax assessment "block books" at the Oakland History Room of the Oakland Public Main Library and newspaper articles in the Oakland Tribune and San Francisco Call. The three-part biography of Volney D. Moody by Daniela Thompson at the Berkeley Architectural Heritage Association website was very helpful.)