Catalina Federal Honor Camp

The Catalina Federal Honor Camp was a labor camp established on Mt. Lemmon used to hold Japanese American men during World War II. The 46 men Held at the Catalina Camp were draft resisters and conscientious objectors who had gone against the exclusion of Japanese from the West Coast of the United States.

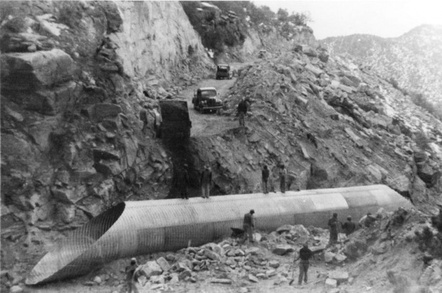

Established in 1939, the prison labor was used to build the popular Catalina Highway connecting Tucson to the high elevation of Mt. Lemmon. Though originally built as a Federal Bureau of Prisons labor camp, it was re-purposed during World War II as a Japanese Relocation Camp.

The primary use of the camp was to house Japanese American draft resisters and conscientious objectors to the war.

Security at the Catalina Camp was actually less stringent than what was found in an average relocation camp. Boundaries were marked by white boulders rather than fences – the harsh terrain surrounding the camp acted as a natural fence.

Gordon Hirabayashi, the most famous of the inmates and the namesake for the now-established campground, was the only inmate sent to the camp for reasons other than draft resisting. Hirabayashi was sentenced to 90 days in the camp for disobeying relocation and curfew orders. Instead of being transported to the Catalina Camp in shackles and chains like the other inmates, he hitchhiked his way from Seattle to Tucson.

Details of the camp

Inmates were charged with the task of building the Catalina Highway. They broke rocks, cleared trees and vegetation, and drilled holes for dynamite. In addition to this, they also maintained the camp by growing food on a small farm below the camp and cooking for the prison population.

The camp was made up of four prisoner barracks, mess hall, laundry, a classroom, vocational shop, administrative building, fifteen cottages for staff, baseball field, and a few utility buildings.

Before the War

The lack of fences was a remnant from before World War II, this is where the designation “Honor Camp” came from. Prisoners of a variety of backgrounds made up the population – bank robbers, immigration law, and tax evasion. While the camp itself was established in 1939, prisoners began to build the highway in 1933. The camp opened its doors after seven miles of highway was completed – the distance of road to the entrance of the camp.

After the War

When the war ended in 1946, the prison labor camp stayed open until 1951 when the Catalina Highway was completed. It was then converted in to a juvenile offenders camp which had a logging and sign making operation. The camp was then turned over to the state of Arizona in 1967 which used it as a youth rehabilitation center until 1973. By the mid-1970’s, all of the buildings had been razed to their foundations.

In 1999, the state of Arizona reopened the site as the “Gordon Hirabayashi Recreation Site.

Timeline

1933 – Construction on the Catalina Highway begins. Inmates housed in tents.

1939 – The Catalina Federal Honor Camp opens its permanent site

1939 – 1946 – World War II era. Camp holds draft resisters and conscientious objectors

1951 – The Catalina Highway is completed

1951 – 1967 – Juvenile offenders camp

1967 – Camp is handed over to the state of Arizona

1967 – 1973 – Used as a youth rehabilitation center

Mid-1970’s – Camp is razed to the foundations

1999 – Present – Gordon Hirabayashi Recreation Site is opened

References

Lyon, Cherstin. "Tucson (detention facility)." Densho Encyclopedia. 14 Jul 2015, 21:54 PDT. 4 Aug 2015, 15:05 <http://encyclopedia.densho.org/Tucson%20(detention%20facility)/>.

United States. National Park Service. "National Park Service: Confinement and Ethnicity (Chapter 18)." National Parks Service. U.S. Department of the Interior. Web. 4 Aug. 2015.

"1999 Story on Naming of Hirabayashi Recreation Site." Arizona Daily Star. Arizona Daily Star, 6 Jan. 2012. Web. 4 Aug. 2015.