Exterior of the Mission. Photo: https://www.gonewiththewynns.com/San-Xavier-Bac-AZ

Information

As Spanish colonists moved north throughout what is currently known today as Mexico, up through Arizona, they were looking for new land to claim and advance the Spanish mission. The Jesuits were in search of new settlements for missions and ended up creating a chain of missions throughout the Sonoran Mountain range. The San Xavier Del Blanc was founded in 1700 by Father Eusebio Kino, a man tasked by the Jesuits to spread Christianity to new Spain. Father Kino was born in Northern Italy on August 10, 1645. He arrived in Arizona, then began exploring the land that is now San Xavier del Bac Mission. Construction of the church began in 1783 and was completed in 1797. The Mission is often referred to as the white dove of the desert, highlighting the bright white stucco finish with the brown desert background. It was named for Francis Xavier, a Christian missionary.

The historic landmark is located 9 miles south of downtown Tucson, on the Tohono O’odham San Xavier Indian Reservation. It is just off of Interstate 19 (exit 92).

History

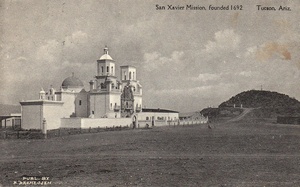

One of the oldest known photos of the Mission.

Father Eusebio Kino founded the San Xavier Mission, beginning construction in 1700, though the church was never completed. He was a Jesuit and began construction of the first mission church on April 28, 1700. In 1767, Charles III of Spain banned the Jesuits from the Spanish lands in America and installed Franciscans to be in charge of the mission. After some indian attacks by the Apache tribe, the mission was rebuilt between 1783 and 1797 by fathers Juan Bautista Velderrain and Juan Bautista Llorenz. The way these men were able to afford to rebuild the church is by using money donated by Sonoran ranchers. Because of all of the local support Juan Bautista Velderrain, and Juan Bautista Llorenz were able to hire the architect Ignacio Gaona and a large work force of O'odham to create the present church. Father Alonso Espinosa constructed the original Jesuit church of the Mission San Xavier after his arrival in 17562. This church was completed in 1762; the walls were remodeled by the Franciscans with added stone and lime mortar walls, it is also possible that the floors were resurfaced. This church, however, is no longer standing- it was dismantled and repurposed for the building of the current standing church between 1781 and 1897 by Father Velderrain. Bishop Henri Granjon constructed a shed in the early 20th century which slightly overlapped with the original 1762 church- the shed's west wall was laid on top of the east wall of the 1762 church2.

The Mission San Xavier del Bac was part of a network of Spanish Colonial settlements in the Pimería Alta, along with the Mission San Augustin and Presidio del Tucson. These three settlements were involved in the Spanish Empire's effort to urge indigenous people to settle, convert to Catholicism, and adopt a Spanish-European way of life. These settlements were usually run by Jesuit or the Franciscan friars, creating expansion of Spanish European culture and influence throughout new lands. These missions had hopes and desires to convert the native Americans to Christianity Aswell as Hispanicize them. Missionaries brought domesticated animals into the equation, including sheep, horses, cows, pigs, goats, and chickens1. Father Alexander Rapicani inventoried the animals kept at the original mission in 1737, which included 240 cattle, 150 sheep, 50 goats, 10 horses, 4 mares, and 2 mules2.

Through the husbandry practices at the missions, animal protein became a more consistent food source in the diet of those residing in the Pimería Alta. Tallow, animal fat used in candlemaking, was harvested by grinding bones up and boiling them to draw out the fat3. Butchering was conducted with metal tools, including knives, handaxes, and cleavers, to separate meat from bone and divide it up into edible portions1. Sawing would not take place in this region until after the colonial period.

After the Independence of Mexico in 1821, San Xavier became part of Mexico. In 1854, following the Gadsden Purchase, San Xavier became part of U.S. rule and part of Arizona Territory. In 1866, Tucson became an incipient diocese and services began at the mission regularly.

In 1872, Sisters of St. Joseph of Carondelet opened a school for the Tohono O’odham children and the building was repaired. In 1887, and earthquake knocked the mortuary wall and destroyed parts of the mission itself. Repairs began in 1905 under Bishop Henry Granjon. In 1978 a group of community leaders formed the Patronato San Xavier which promotes the conservation of the mission. The preservation continues to this day when funds are available. Donations can be made by contacting [email protected]. You can also send donations by doing the following:

Send your tax-deductible donation to:

Patronato San Xavier

P.O. Box 522

Tucson, AZ 85702

520-407-6130

The Franciscans returned in 1913 and recently, the mission became a separate non-profit entity. Franciscan Sisters of Christian Charity have taught and still teach at the school since 1872 and reside in the Mission convent.

Timeline (from http://www.sanxaviermission.org/History.html)

1692 Father Kino visits the village of Wa:k

1700 Father Kino begins foundations on a church never built

1711 Father Kino dies in Magdalena, Sonora, Mexico

1756 Father Espinosa constructs the 1st church

1767 Jesuits are expelled from New Spain

1768 Spanish Franciscans take over the Mission

1783 Construction begins on the present church

1797 The Mission church is completed

1821 Spanish Franciscans leave

1846 Cooke's Mormon battalion passes by the Mission

1854 Gadsden Purchase puts the Mission inside the United States

1859 Santa Fe diocese begins first repairs of the Mission

1887 Earthquake damages the Mission

1905 Bishop Granjon begins major repairs

1913 Franciscans return to the Mission

1939 Lightning strikes the West Tower

1953 Church facade is restored

1963 San Xavier becomes a National Historic Landmark

1978 Patronato San Xavier established to preserve the Mission

1989 Leaking walls force emergency restoration

1992 Conservators begin a 5-year rescue effort of the interior

Today the restoration continues when funds are available.

Zooarchaeology of the San Xavier Mission

Methods

Samples involved in this analysis were excavated in the 1972 field season by Bernard Fontana, from Granjon Room 2. Specific provenience information as provided by the excavation stated that these samples were from the north 1/2 bottom level, south 1⁄2 level 5, trench E-6 level 1, unit 4, and the remainder of Granjon Room 2, down to a level of 1.00m from the top of the east wall. Samples from the Mission San Xavier Granjon Room 2 were analyzed from January 30, 2019 until April 11, 2019.

The Mission Cocòspera faunal codes were used to identify and record these samples. Sizes of mammals which could not be identified to lower taxonoimic categories were categorized by size into "small mammal," "medium mammal," and "large mammal" categories.. Mammals were considered small if they were no larger than a breadbox and considered large if they outsized an ottoman. Small ungulates included sheep and deer, and large ungulates were considered horse or cow sized.

The animal bone was analyzed and recorded by hand on a chart, and later transferred to digital spreadsheet. Minimum Number of Individuals (MNI) was calculated for the lowest taxonomic categories, demonstrated (Table 1)4. The species list is summarized in Table 25, generalizing the species into five categories: wild mammals, domestic mammals, domestic birds, tortoises, and unknown. The function of this is to identify broad overarching patterns, comparing how many domesticated animals are represented in this analysis versus the wild hunted animals. A pie chart generated from this data excludes the unknown specimen as this does not allow for an accurate representation of the distribution of animals at the mission. For the most commonly identified species, element distribution was analyzed. This represented sheep, cows, and consolidated Lepus alleni, Lepus californicus, and Sylvilagus audubonii into one category of Leporidae due to how similar these species are in size and ecological role. Butchery patterns identified were also summarized, however, due to how fragmentary much of the sample was and how the fragmented material demonstrated most of the butchery, table three6 uses broad categories to encompass more of the butchering marks, burning, and gnawing than would otherwise be seen in specific species taxa. These broad categories include medium ungulates, incorporating sheep and deer, small mammals, incorporating Leporidae, and large mammals.

Results

Species most commonly identified were Ovis aries, Bos taurus, and Leporidae- Lepus alleni, Lepus californicus, and Sylvilagus audubonii. There was one identified element from a mule deer, at least one chicken and one tortoise are represented among this sample. For the most part, however, the sample revealed small or large mammals, and small or large ungulates. The specimen included in this faunal analysis exhibited a significant amount of weathering. Many bones demonstrated post-mortem breakage and recent breakage. Due to this, few bones could be identified, and even fewer given a species designation.

Rodent gnawing was observed on some unidentifiable specimen, but no carnivore gnawing was observed. Hack marks were the most common butchery marks observed, some cut marks were seen. Most hack marks were diagonal or transverse to the bone, whereas the cut marks examined were primarily longitudinal. There were many cases of "bend and break" butchering, where there's evidence of a hack, but rather than hacking directly into the bone, a portion was snapped off, leaving a straight ridge and a depression. Also noted was burning evidence on the bones; many had smudges of ash on them. Some indeterminate bones were completely black from burning, and there were a few calcined bones among the sample as well.

Two bones from the remainder of unit two were found to have a unique texture which was not represented anywhere else in the sample. This texture is consistent with acid damage. One element was a complete chicken radius, and the other a long bone fragment. Both specimens were larger than could easily be ingested, leading to exposure to stomach acid, suggesting that there may have been acid in the soil.

Discussion

The butchery pattern identified is consistent with the Spanish colonial butchering style, suggesting that this sample is from some time between 1700 and 1850. It is likely associated with the original 1764 church. The site would have been inhabited during the Spanish colonial period, so many of the bones demonstrate colonial activity. However, this does not explain the weathering of the sample.

Most of the sample exhibits recent breaks, suggested by the discoloration of the bones. This likely is a result of site taphonomy rather than activity from the time period. Tallow harvesting was common among the Spanish colonies, but bones which have been processed for tallow do not demonstrate the recent breakage pattern seen here. The building of the shed in the early 20th century by Bishop Granjon is the most probable cause of the weathering observed among this sample. The construction of the shed so close to the site likely resulted in great disturbance of the archaeological site, including the sample represented here.

The identified species here suggest that animal husbandry was common among the missions, as seen in the presence of domestic sheep and cows. However, this subsistence strategy did not account for all animal presence, as wild rabbits and deer were represented as well. This suggests that though the missionaries succeeded in introducing and maintaining domesticated animals, traditional hunting methods continued. The missionaries attempted to instill a Spanish-European way of life and alter the culture among the O'odham natives; they had mixed success with animal husbandry, as indicated by the wild fauna represented in this analysis.

Architecture

Interior of the Mission. Photo: http://www.ontheroadagainforyou.com/san-xavier-mission-del-bac-corona-de-guevavi-tubac/

The main building of the mission is in the shape of a Latin cross, showing how the influence was strictly Spanish, Piman influence was absent from the structure and architecture outside of some desert building materials. The building has two octagonal towers in the front, a large dome covering the transept crossing, with smaller domes flanking the north and south. The mission includes 6 primary areas: the mortuary chapel, dormitory, patio, garden, convent, and the main church. The Interior of the church was built with adobe bricks set in Lime mortar, with the exterior primarily white stucco. The interior of the mission is where the artisanship and Spanish influence can be seen throughout. The interior features iconic religious imagery, paintings, and wall carvings, with the roof being structured with masonry vaults. Wooden statues of saint Xavier and Mary are embedded in the wall behind the altar. Other saints and native Americans have carved statues throughout the mission and show appreciation for the past lives of original members of the settlement. The architect of the mission was Ignacio Gaona. The interior is full of paintings, frescoes, statues and carvings with displays of New Spain and Native America art and motifs.

There is not much known about the people who decorated, but it is believed to commissioned by Father Velderrain’s successor. Although the exact artists of the interior are unknown, there are symbols and architecture styles that can give some insight into the history of the design. Images of seashells, which can be seen all throughout the missions window treatments and other detailed interior elements, are a symbol of pilgrimage in relation to the voyage the patron saint of Spain, Santiago or James the Greater made. Also, the architecture contains elements seen throughout the Baroque era that involve dramatic yet playful elements. These elements include: faux doors, marbling, theatrical curtain displays, and an overall sense of symmetry and balance.

The mission is considered the finest example of Spanish mission architecture in the U.S. and was declared a National Historic Landmark in 1960.

Photo: http://thegenealogysearch.blogspot.com/2010/11/wordless-wednesday-almost-san-xavier.html

The Restoration

In 1887, a massive earthquake struck the mission causing the church façade and mortuary wall to be damaged. Due to these circumstances, extensive repairs were needed. In 1905, Bishop Henry Granjon thought it was time for the church to finally be fixed. He had the entire church replastered and repainted. He had new walls and arches added to the structure to help create a more secure building. In 1908, Granjon had a shrine of the Virgin Mary built 300 feet east of the church, it was meant to replicate the Grotto of Lourdes. The Church also saw a need for repairs in 1939 when a lightning strike hit the Western Tower Lantern.

In 1978 a group of community leaders decided they wanted to create a conservation group for Mission San Xavier. They called this group the Patronanto San Xavier. Shortly after this group was formed however this mission saw more problems. Water was seeping into the west wall of the church's sanctuary, and because of this the Patronanto were forced to take action. It took five years for the Patronanto to finish but when they did the Misson San Xavier was almost as good as new.

Today

The mission is still run by the Franciscans and still serves the Native community by whom it was built. The church is open to the public daily with the exception of church services. The mission is very important to the Tucson community because of its rich history. This type of Spanish colonial architecture is not common in the United States so the mission is a very important landmark. The mission itself has had its fair share of damage and the restoration of the church continues today and is very important. According to the mission’s website, the mission remains a testament to the endurance of culture throughout its history. About 200,000 people come each year to witness the beautiful architecture and history that this Mission has.

Besides holding mass, the mission also has a museum and gift shop. The museum is filled with historical artifacts and is free to the public, however donations are accepted and greatly appreciated. The gift shop has various items ranging from t-shirts to candles to authentic baskets made by members of the Tohono O’odham tribe.

Hours

Church: 7:00 am - 5:00 pm daily

Gift Shop Hours: 8:00 am - 5:00 pm

Museum Hours: 8:00 a.m. - 4:30 p.m. (Closed Thanksgiving, Christmas, and Easter)

Office Hours: 8:30 am - 4:30 pm (Monday - Friday)

Mass Schedule

Saturday Vigil: 5:30 pm

Sunday: 8:00 am, 11:00 am, 12:30 pm

Monday - Friday: 6:30 am (in the Juan Diego Chapel)

Sources: http://www.sanxaviermission.org

Sources: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mission_San_Xavier_del_Bac

Sources:https://www.nps.gov/nr/travel/american_latino_heritage/san_xavier_del_bac_mission.html

*Sources: references for the zooarchaeological analysis are all non-digital print books, located in the University of Arizona's Arizona State Museum library.

1Cameron, Judi L., Jennifer A. Walters, Barnet Pavao-Zuckerman, Vince M. LaMotta, and Peter D. Schultz. 2006. Faunal Remains In Rio Nuevo Archaeology, 2000-2003, pp. 13-18. Technical Report No. 2004-11. Desert Archaeology, Inc., Tucson, Az.

2Cheek, Annetta Lyman. 1974. The Evidence for Acculturation in Artifacts: Indians and Non-Indians at San Xavier Del Bac, Arizona:295.

3Fontana, Bernard L., James E. Officer, and Mardith Schuetz-Miller. 1996. The Pimería Alta: missions & more. Center, Arizona State Museum, Univ. of Arizona, Tucson, AZ

4Table one:

5Table two:

6Table three: