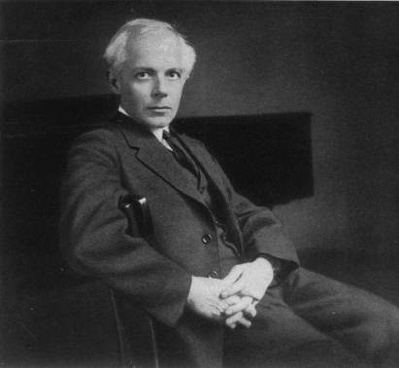

Bela Bartok Béla Bartók, 1927, photographer unknown (Wikipedia) Born: March 25, 1881, Nagyszentmiklos, Transylvania (now part of Romania)

Bela Bartok Béla Bartók, 1927, photographer unknown (Wikipedia) Born: March 25, 1881, Nagyszentmiklos, Transylvania (now part of Romania)

Died: September 26, 1945, in West Side Hospital, New York City

Married: Márta Ziegler; Edith "Ditta" Pásztory

Children: Béla III; Péter

Béla Bartók was a Hungarian composer and pianist, considered to be one of the greatest composers of the 20th century. He wrote some of his last compositions while staying in Saranac Lake.

His collection and analytical study of folk music helped create the field of ethnomusicology.

Dr. Henry Leetch was his physician when he was in Saranac Lake.

Bartok was a member of the International Committee on Intellectual Cooperation, an advisory organization for the League of Nations. This committee, which promoted international intellectual/cultural exchange, had many other distinguished members, including Albert Einstein. Einstein summered in Saranac Lake in 1936 and 1937.

In 2022, Historic Saranac Lake acquired a collection of personal effects that belonged to Mr. Bartók, including photos, clothing, and other memorabilia. Included in the collection is a ticket stub from the premiere of “Concerto for Orchestra" at Symphony Hall in Boston on December 2, 1944. A note in pencil at the top reads, "Mrs. Bartok." The Bartók collection will be displayed in the future expanded museum in the Trudeau Building, tentatively scheduled to open in 2025.

See essay by Amy Catania 3/14/2022 https://www.historicsaranaclake.org/history-matters-blog/walking-in-bartoks-shoes

In 2022, Historic Saranac Lake hosted, "Celebrating Bartók," a series of online programs supported by This discussion series has been made possible in part by the National Endowment for the Humanities: Democracy demands wisdom. The programs can be viewed here: https://www.historicsaranaclake.org/celebrating-bartok.html

A brick at the Saranac Laboratory has been dedicated in the name of Béla Bartók by Ruth Chasolen.

A brick at the Saranac Laboratory has been dedicated in the name of Béla Bartók by Ruth Chasolen.

Adirondack Daily Enterprise, February 2, 1996

Bartok's creative last summer in Saranac Lake in 1945

By MARY B. HOTALING Special to the Enterprise

SARANAC LAKE - In 1945 the great Hungarian composer Béla Bartók spent the last summer of his life in Saranac Lake, writing two pieces, his Third Piano Concerto and his Viola Concerto. Fifty years later, Bartók 's reputation has soared, but the cabin at Bartok Cabin 89 1/2 Riverside Drive] where he stayed is near collapse.

Bartók, 59, arrived in the United States with his wife Ditta late in 1940; their teen-age son Peter followed later. They had voluntarily exiled themselves from their home in Hungary, where Bartok's music is rooted, rather than live under the rule of the approaching Nazis, whom Bartók despised. Though not yet well-known in the United States, Bartók was famous in Hungary as a pianist, a composer and a collector of the ancient native folk songs of Eastern Europe. In New York he had a position at Columbia University studying and transcribing Harvard's Milman Parry Collection of Serbo-Croatian folk songs in a sound-proof room. It was work that Bartók loved, and he was the best possible person to do it, but the money supporting his research was uncertain and renewed only six months at a time. Because of the war, his funds in Hungary were not available to him.

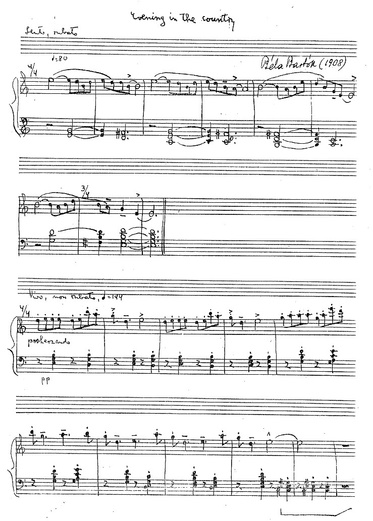

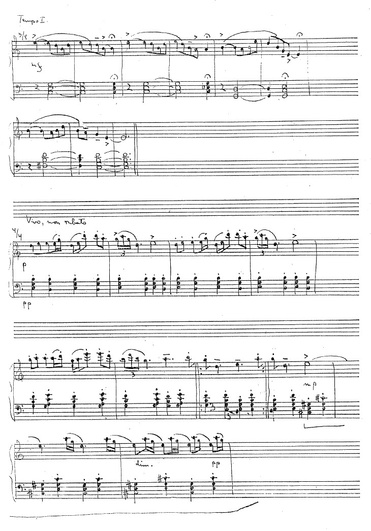

When Bartok was in Saranac Lake in 1943, he met a woman who gave piano lessons, Pilar Benero. He copied out one of his children's pieces from memory, named it in English, and signed and dated it, so that she could use it to teach her pupils. Photocopy courtesy of Joe Benero.

When Bartok was in Saranac Lake in 1943, he met a woman who gave piano lessons, Pilar Benero. He copied out one of his children's pieces from memory, named it in English, and signed and dated it, so that she could use it to teach her pupils. Photocopy courtesy of Joe Benero.

At the same time that he was having difficulties with money, his health was also declining. The American Society of Composers, Authors and Publishers (ASCAP) stepped in to provide the best doctors and hospitals. Bartók 's illness was at first thought to be a recurrence of the tuberculosis he had had as a young man, and one of his doctors in New York was Edgar Mayer, well known here as the director of Will Rogers Hospital. Later a diagnosis of leukemia was made, but as there was no effective treatment at that time, the gravity of his condition seems to have been downplayed to him.

Twenty-five years later, Dr. Mayer wrote a remembrance of Bartók as "very soft spoken and talking very little. He never complained!! With high fever up to 102° -103° he sat up writing music from his head, composing from memory. He hated to be disturbed even by his doctor, he did not believe we knew what was wrong with him anyhow.

"To compose he needed great silence. He stuffed his ears with ebony earstoppers. One day, one of his ebony earpieces got lost and he was in great distress. I had the fortunate idea of trying an earpiece from my stethoscope. This he could not forget, it was the greatest good deed I did for him. It helped him more than any medical service I gave him."

Mayer and his colleague Dr. Israel Rappaport sent Bartók to Saranac Lake for the summer of 1943. That summer and the next, on the recommendation of Dr. Henry Leetch, the Bartók's stayed with Mrs. Margaret Sageman, who owned a large cure cottage at 32 Park Avenue, and lived in a smaller bungalow behind it. In less than two months, Bartók composed the Concerto for Orchestra. 1

When the Bartóks returned to Saranac Lake in 1945, they moved into a four-room cabin at 89 1/2 Riverside Drive. Mrs. M.A. Levy, with whom the Bartóks had become friends in previous summers, had helped them find it, next door to her house at 93 Riverside Drive. The cabin stood in the back yard of a house rented by Maks Haar, who worked for Lederle, and his wife, the former Ida Weinstock, who was raised in Saranac Lake. For $15 a month, the Haars sublet the cabin to the Bartók s, who inscribed the Haars' guest book: "We are happy indeed to stay in this wonderful quiet place."

When the Bartóks returned to Saranac Lake in 1945, they moved into a four-room cabin at 89 1/2 Riverside Drive. Mrs. M.A. Levy, with whom the Bartóks had become friends in previous summers, had helped them find it, next door to her house at 93 Riverside Drive. The cabin stood in the back yard of a house rented by Maks Haar, who worked for Lederle, and his wife, the former Ida Weinstock, who was raised in Saranac Lake. For $15 a month, the Haars sublet the cabin to the Bartók s, who inscribed the Haars' guest book: "We are happy indeed to stay in this wonderful quiet place."

It is not known when the rustic cabin was built, though it seems likely to have been a summer curing' facility for tuberculosis patients when the house was a cure cottage called Balsam Manor. Because the steep site limits the best angles for photography, no historic photos of the house show the cabin, though it may have been present when they were taken. Maryland Avenue behind the cabin was probably still undeveloped in 1945, and Ida Haar remembers going for walks with Bartók in the woods.

The entrance to the four-room cabin was through a small porch. Straight ahead, one door opened into the living room, and another to the right led directly to the simple kitchen. There was a brick fireplace in the living room; Bartok loved open fires along with all real, natural things. Ceilings throughout were very low, about 6'6". Described as "a small makeshift place" and "a hovel or hut," it was very simply furnished "with two cots, a small table, chairs that are gone long ago," and no piano, according to Peter. The composer brought with him a "minimum of necessities, two kinds of manuscript paper (one for pencil, one for India ink) and writing instruments."

Bartók wrote about the cabin in a letter to Peter on July 8, calling it "very quiet, but very simple... the bath water must be heated in a stove... . The ice-box must be fed real, natural ice." These comments were high praise from Bartók, who greatly valued quiet, simplicity and closeness to nature. Peter observed that "my father was obviously contented; his surroundings were as spartan as the interior of a Hungarian peasant cottage - a reminder of a world with such fond associations for him." Here, wrote Peter, "he found the peace and tranquility suitable for composing " In these plain rooms, Bartok wrote his last two works, the Viola Concerto and the Third Piano Concerto. Ditta wrote to their friend Agatha Fassett that " Bartók was feeling so well it was almost beyond belief. He wandered long hours in the woods and never showed any weariness when he returned home."

Bartók wrote about the cabin in a letter to Peter on July 8, calling it "very quiet, but very simple... the bath water must be heated in a stove... . The ice-box must be fed real, natural ice." These comments were high praise from Bartók, who greatly valued quiet, simplicity and closeness to nature. Peter observed that "my father was obviously contented; his surroundings were as spartan as the interior of a Hungarian peasant cottage - a reminder of a world with such fond associations for him." Here, wrote Peter, "he found the peace and tranquility suitable for composing " In these plain rooms, Bartok wrote his last two works, the Viola Concerto and the Third Piano Concerto. Ditta wrote to their friend Agatha Fassett that " Bartók was feeling so well it was almost beyond belief. He wandered long hours in the woods and never showed any weariness when he returned home."

All the rest of the time was devoted to his work, to those two compositions he was so anxious to finish before the summer came to an end. The Viola Concerto for (William) Primrose was already sketched out in its final form, and as for the orchestration, "all that was missing were the notes." For Bartók, that meant no more than finding time to put them down on paper. And the Piano Concerto . . . was practically finished, except for a few of the concluding measures."

Ida Haar remembers that "Ditta came into our house where we had a piano, and she "practiced there because they didn't have a piano in the cottage." At Ida's request, Ditta gave a free concert that summer in the Jewish Community Center on Church Street (where the Paul Smith's College dormitory now stands.) Mrs. Levy, also involved in the concert, was disappointed that this exposure did not lead to paying professional engagements for Ditta.

Local lore has it that Ditta went next door to the Levy's house to play the compositions that Bartók was writing on the piano there, where her husband could hear it from the cabin.

At that time Deerwood, a highly regarded music camp on Upper Saranac Lake, put on a series of concerts in the Town Hall on Friday nights When Bartók's music was on the program, the composer attended, and Chapin remembers "the rousing response that came to him!" Fifty years later, the memory of that Friday evening still thrills her.

During that summer the war in Europe finally ended and friends in Budapest cabled Bartók, asking him "to return and take his place in the reorganized parliament." He was "pleased to be remembered, but seemed to realize he would never make the trip.

Around Labor Day, the Bartóks, accompanied by Peter, left Saranac Lake by train for New York. In September, Bartók's health suddenly failed and he was ordered into the hospital. Bartók said to Peter, "Can I go tomorrow? There is something I want to do here." Not knowing the seriousness of his father's illness, and thinking that the hospital stay would restore him to a measure of health, Peter convinced him to go that day. But before they left, on his father's instructions, Peter added seventeen measures to the manuscript of the Piano Concerto.

On September 26, 1945, less than a month after leaving Saranac Lake, Béla Bartók died in West Side Hospital, New York.

The Concerto for Orchestra, written during Bartók's first summer in Saranac Lake, was the first piece he had written in the three years since leaving his homeland. Three of the four compositions he created in the United States were written in Saranac Lake. This quiet, natural environment truly nurtured Béla Bartók's creative genius.

June, 2006 Adirondack Daily Enterprise:

"....In a ceremony at the Hungarian Consulate in New York City on May 31, Ambassador Dr. Gabor Horvath presented a citation to Mary Hotaling, executive director of HSL, for [the restoration of the Bartók Cabin]. HSL was also given a portrait of Bartók painted by Veronika Simon. The painting will be on display at this summer's concerts at Cobble Spring Farm.

In 2004, Marta Schneider, Hungarian deputy minister of culture presided in a ceremony to install a brass plaque in the cabin, inscribed with a portrait of Béla Bartók and the words, "In the summer of 1945 Béla Bartók, the great Hungarian composer, found peace and inspiration in this place and here completed his last works."

August 18, 1970 Adirondack Daily Enterprise

Mrs. Sageman Remembers the Bartoks

Meaning no disrespect to Robert Louis Stevenson, it may someday be said that the most famous man ever to live in this town was the Hungarian composer Bela Bartok. Considered by many to be the Beethoven of this generation, the composer predicted that he would not be appreciated for a hundred years after his death, and much of his music is only now being discovered. Three of his best known pieces, the Concerto for Orchestra, the Viola Concerto for William Primrose and the Piano Concerto No. 3 for his wife, were written here in Saranac Lake.

Driven to the United States in 1940, by World War II, Bartok came to Saranac Lake during the 3 years from 1943 to 1945, mainly in the summers. The first two years he stayed with Mrs. Margaret Sageman in her curing establishment on Park Ave. The third summer he lived in a cottage on the Manko property, behind 89 Riverside Drive. Mrs. Sageman, who was a TB nurse for 32 of the 50 years she has lived here, remembers her famous patient well. Dr. Henry Leach, whom Bartok nicknamed "Mr. ASCAP'' because the musicians' association was paying for the composer's treatment, directed him to Mrs. Sageman. "He and his wife and son came with him," she says. "He was quite happy here- at least he seemed to be. I let him live as he wanted to live."

Though actually suffering from Leukemia, Bartok's treatment was the same as for a tuberculosis patient — a little medication, "good substantial food," fresh air and rest. According to his son Peter, who was here in Saranac Lake a few weeks ago, even during the last summer of his life on the mountains, Bartok felt well enough to work and even hike a little. He died within a month after returning to New York City in 1945.

One of the things Mrs. Sageman remembers most vividly about her patient was often being surprised by him. As she tells it, "He wore sneakers or something. He didn't knock, he just came in. The first thing I know, he'd pat my shoulder, (Mrs. Sageman still starts at the memory) and he'd be right there beside me.” She also shakes her head over the fact that Bartok took the New York Times every Sunday and left it scattered all over her living room. His bedroom is basically the same as it was in 1945, she says, "but if you could have seen it when he had it! He had the New York Times stacked up almost to the ceiling in one corner."

Ditta Bartok, the composer's second wife, had been his protegee, his landlady reports, and was a "marvelous pianist." Mrs. Sageman's job Included finding a place for her to practice. As a member of the Saranac Lake school board she arranged through Superintendent Howard Littell for Ditta to use a piano at the high school, where she eventually gave two concerts, one for students and one for faculty.

Of Mrs. Bartok, Mrs. Sageman recalls, "I used to tease her, because every time she told her age she'd take off two years. I said, 'Ditta, you have to stop. You'll be as old as Peter." Ditta "never kept an appointment" and during the summer when she brought her husband up to Mrs. Manko's she ran into trouble with wartime living arrangements. "She came to me,” recollects Mrs, Sageman, "she didn't have stamps and couldn't get food. Ditta was the kind of person who would buy a steak and give them the whole book," and unscrupulous people took advantage of her. ASCAP was no longer supporting the Bartoks, so Mrs. Sageman "got them food and food stamps and got them started."

One of her most dramatic recollections concerns Ditta's visit after her husband's death. "Peter called telling me his father had died, an his mother was very depressed," she recounts. "I didn't have a place for her, but I found a place for her over on Franklin Ave. With Mrs. Something or other... the number was 50 something.Then I got a call from this woman saying she had disappeared.”

"I got in my car and rode out to the lake, thinking she had decided to end it all. She was deeply depressed."

Seeing Ditta walking "with her head down," Mrs. Sageman drove up the road and circled around, then came back. "I said, 'Imagine finding you on Lake Flower Avenue. I thought you lived on Franklin Avenue.'” She got in the car, and she put her head down on my shoulder, 'Oh, Marguerita,' she said, and she wept bitterly."

Bela Bartok, though ill ("he couldn’t have weighed more than 100 pounds") worked steadily here. "He was very busy," Mrs. Sageman reported. "I think he stayed up nights; there was always a light from his room. He played here in the living room over at the big house," she also recalls. "Such a frail man to get so much out of a piano. Such a little man. So delicate looking, such penetrating blue eyes.”

"He used to wear a charcoal gray cape coat that covered him all up. He'd go for a walk and he said children would stare at him."

Bartok and Mrs. Sageman came to be comfortable friends. "He told me he didn’t like my piano," Mrs. Sageman [said], "and I said, 'I don't either.' He was very frank." Once Mrs. Sageman remembers remarking that she liked Brahms' lullaby. Bartok looked at her and said, "'I’ll play it for you,' he said. And he sat down and played for an hour."

When he wasn't working, the composer was "always looking for butterflies, worms, and what have you... Any kind of a bug." An amateur naturalist since childhood, Bartok wrote letters to his son Peter in the Navy telling of “watching the chickmunks.”

Mrs. Sageman thought very highly of Bartok, finding him to be brilliant, kind, humble, and with a great sense of humor. One day, when he was out, she had her porch painted and signs put up. Coming back, "He walked on wet paint upstairs... they lifted him down the stairs and cleaned his shoes." It became a joke: "The little professor walked through the paint.””Everyone laughed, " Mrs Sageman says, adding "and he laughed with them.”

Comments

Footnotes

1. According to program notes by Phillip Huscher for Bartok composed the Concerto for Orchestra between August 15 and October 8, 1943, and it was first performed on December 1, 1944.