HAHNDORF and its ACADEMY by PROF. R.W.V. ELLIOTT

Extract from 'WALKABOUT' Magazine - April, 1964

GLEN OSMOND is the front door of the Mount Lofty Ranges. Today, in summer, a constant stream of cars winds up the smooth lanes of the Prince’s Highway, escaping in speedy comfort from the heat of the Adelaide plain to the cooler airs of the hills. A hundred and twenty—five years ago another procession was winding its way up Glen Osmond, but without a highway as its guide and without a fleet of cars.

Up they climbed, step by laborious step, through the trackless Australian bush, in the hottest month of the year, 197 adults and children; 52 families of German Lutheran immigrants, carrying all their possessions on their backs.

When at last they reached the top of the ridge, so their chronicler reports, they turned back once more to look across the plain, with its infant settlement of Adelaide, to the waters of the gulf and the good ship Zebra. And they joined in the singing of Paul Gerhardt’s lovely evening hymn, Nun ruhen alle Walder:

The last faint beam is going, / The golden stars are glowing, / In yonder dark-blue deep.

And then they turned eastward again towards their goal.

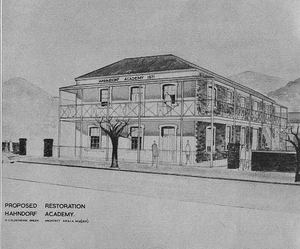

Nowadays Hahndorf Academy is gradually falling into disrepair, having served as a hospital, offices, and private dwelling since it closed its doors during the first world war. Efforts are being made to preserve it.The Zebra, under Captain Dirk Hahn, had arrived in South Australian waters late in 1838, and on January 2, 1839, the German migrants had disembarked at Port Adelaide. Their patience and even temper throughout the long and tedious voyage had so impressed Captain Hahn that he determined to see them happily settled in the colony. “Seldom have I seen a more touching spectacle,” he wrote, “than when at the fall of evening, the whole deck was filled with people on their knees, and all united in praying to God for His blessing and help in their undertaking.” It was largely through Hahn’s intercession that land was found for the migrants, 150 acres a few miles from Mount Barker in a picturesque and fertile valley of the ranges. The original lease was for one year, and the settlers were also to be given some livestock, provisions and assistance for building a church. If, at the end of the year, the venture proved successful, as much additional land as each family could work was to be made available to it at a reasonable rent.

Nowadays Hahndorf Academy is gradually falling into disrepair, having served as a hospital, offices, and private dwelling since it closed its doors during the first world war. Efforts are being made to preserve it.The Zebra, under Captain Dirk Hahn, had arrived in South Australian waters late in 1838, and on January 2, 1839, the German migrants had disembarked at Port Adelaide. Their patience and even temper throughout the long and tedious voyage had so impressed Captain Hahn that he determined to see them happily settled in the colony. “Seldom have I seen a more touching spectacle,” he wrote, “than when at the fall of evening, the whole deck was filled with people on their knees, and all united in praying to God for His blessing and help in their undertaking.” It was largely through Hahn’s intercession that land was found for the migrants, 150 acres a few miles from Mount Barker in a picturesque and fertile valley of the ranges. The original lease was for one year, and the settlers were also to be given some livestock, provisions and assistance for building a church. If, at the end of the year, the venture proved successful, as much additional land as each family could work was to be made available to it at a reasonable rent.

This, then, was the goal of the party trekking up Glen Osmond in the early months of 1839. They reached their destination in March, and in grateful acknowledgement of Captain Hahn’s untiring efforts on their behalf, they called their new home Hahn’s village — Hahndorf.

The venture did prove successful. Within a few years the settlers had paid off their most pressing debts and acquired new land, had built their first church and school, and had established several thriving local industries. J. F. W. Wittwer operated a water-mill on Cox’s Creek and, when this was destroyed by fire, he worked at the windmill, built in 1842 by F. R. Nixon, on the range of hills between Hahndorf and Mount Barker, still a prominent landmark on Windmill Hill. A blacksmith’s shop, a tannery, and other signs of expanding activity followed as the township grew.

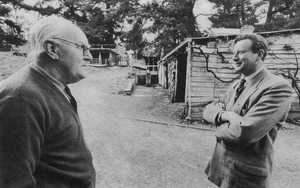

Hahndorf's most famous resident is Sir Hans Heysen, doyen of Australian landscape artists, who lives on, still painting at 87. He is seen speaking to Walter Wotzke, Director of the Hahndorf Gallery.It was hard going at first. The ground had to be cleared and dug over with fork and spade. The barley and wheat were hand sown and the ground harrowed with a forked branch fitted with wooden teeth. Vegetables were sown, and these, together with the butter and eggs soon produced, found a ready market in Adelaide. All produce had to be laboriously carried down the steep track to the city on foot, usually by the women and older girls. This labour, fortunately, their descendants of to—day are spared, but some of the old-domestic crafts still thrive. Hahndorf women still use some of their old recipes for cheeses and sausages and German cake (Streuselkuchen) whose popularity is such that, at the Traditional German Food Fair held in aid of the Academy Restoration Appeal in 1962, several of the food stalls were sold out within half an hour of opening.

Hahndorf's most famous resident is Sir Hans Heysen, doyen of Australian landscape artists, who lives on, still painting at 87. He is seen speaking to Walter Wotzke, Director of the Hahndorf Gallery.It was hard going at first. The ground had to be cleared and dug over with fork and spade. The barley and wheat were hand sown and the ground harrowed with a forked branch fitted with wooden teeth. Vegetables were sown, and these, together with the butter and eggs soon produced, found a ready market in Adelaide. All produce had to be laboriously carried down the steep track to the city on foot, usually by the women and older girls. This labour, fortunately, their descendants of to—day are spared, but some of the old-domestic crafts still thrive. Hahndorf women still use some of their old recipes for cheeses and sausages and German cake (Streuselkuchen) whose popularity is such that, at the Traditional German Food Fair held in aid of the Academy Restoration Appeal in 1962, several of the food stalls were sold out within half an hour of opening.

It is a splendid tribute to these German men and women that, amid all their early struggles and strenuous toil, they placed importance on the worship of their God and the education of their children. According to one contemporary account: “They rise early and work late, and are moderate and contented as to food and accommodation, and cheerful and pleasant in their intercourse with their neighbours ... At the end of the week they like to assemble in their own Village for divine worship and sing the songs of Zion in a strange land.” Hahndorf’s two fine Lutheran churches of St. Michael’s (dedicated in 1859, to take the place of the original mud—wall building) and St. Paul’s (1890) are constant reminders of the religious ardour of the pioneers.

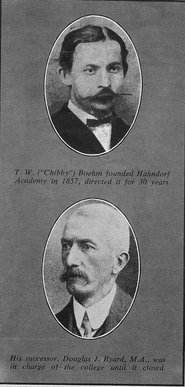

The building which housed the first Lutheran community school is now the home of the Hahndorf art gallery, known all over Australia and a fitting tribute to Hahndorf’s most distinguished resident, the great Australian painter, Sir Hans Heysen. A native of Hamburg, Sir Hans, now in his eighty—seventh year, is still at work upon those serene landscapes of hills and gum trees which have made the Hahndorf neighbourhood familiar to thousands all over the world. The gallery, now a well-preserved, white-washed building of two rooms, early proved inadequate as a School, and in 1857 its director, T. W. Boehm, opened a private institution of higher learning in his own cottage next door. The object of the new school, which Boehm proudly called The Hahndorf Academy, was to provide “a sound and good English and German education, in order to enable its pupils to enter the learned professions, or to prepare them for commercial life” –-- at two guineas a quarter for day-scholars and from 10 to 13 guineas for boarders.

“Chibby” Boehm, a small figure beside his big wife and wearing his invariable frock coat, was well equipped to carry out these laudable aims. For three years he had studied in the tiny “pioneer Lutheran college of the southern hemisphere” at Lobethal, about 15 miles north of Hahndorf, which Pastor G. Fritzsche had founded a few years earlier. After completing his studies there, followed by some practical training in the Barossa Valley, another area of German settlement in South Australia, Boehm returned to Hahndorf to take charge of its community school. He had acquired a remarkable store of learning by the time he opened his academy, and, as he gathered around him a number of capable teachers, its reputation soon spread. The little cottage (the now much-restored one—storey building at the rear of the main building) proved inadequate before long, and in 1872 the main academy building with its corner tower was erected facing the Balhannah road.

Perhaps the expense proved too much for Boehm; perhaps it was the opening of government schools in Adelaide which compelled Boehm to sell his school to the Lutheran Church as a seminary in 1876. Probably there were several reasons, but the interregnum did not last long. In 1883 Boehm, who had remained at the seminary as a teacher, once again acquired possession of the school at the same price, £700, which the church had paid him seven years earlier. In the meantime, however, further building had proved necessary and a new large central wing now joined the front and rear portions into the one compact building which still stands.

Perhaps the expense proved too much for Boehm; perhaps it was the opening of government schools in Adelaide which compelled Boehm to sell his school to the Lutheran Church as a seminary in 1876. Probably there were several reasons, but the interregnum did not last long. In 1883 Boehm, who had remained at the seminary as a teacher, once again acquired possession of the school at the same price, £700, which the church had paid him seven years earlier. In the meantime, however, further building had proved necessary and a new large central wing now joined the front and rear portions into the one compact building which still stands.

During the interregnum 13 Lutheran teachers had graduated from the seminary, some of whom later entered the ministry. One of these graduates was Dr. A. Brauer. the author of Under The Southern Cross.

But life was not all hard work for the Hahndorf scholars, and there are records of school—boy fun and ritual. End of term was always marked by a pillow-fight between the rival dormitories, and to keep the Boehm family and the masters away from the battleground the tower door was fastened and the stairways barricaded. By 1886, however, “Chibby” had had enough of his rumbustious charges, and he finally sold out and retired to live with one of his children in Victoria, where he died in 1917.

The new owner and headmaster of the school was an Englishman, Douglas J. Byard, who had come to South Australia in 1884. Educated at Clifton College, a Master of Arts of Oxford, and an Anglican lay preacher, Mr. Byard must have been the very antithesis of the German Lutheran pedagogue from the Lobethal bush seminary. But he spoke fluent German, and the mingling of boys from English and German families, which had been a feature of the school from its early days, continued.

The school, now renamed the Hahndorf College, continued to flourish and came to play a leading role in the community life of the hills. Reminiscing as recently as 1956, two old boys recalled their school-mates walking, riding, bicycling to school from Balhannah, Woodside, Mount Barker, even Mount Lofty. Boarders hailed from as far as Queensland. Sport became more important and the gymnasium, part of whose foundation walls is still visible in the Academy grounds, was, in its time, reputed to have been the finest in the southern hemisphere.

On the academic side the college was active and successful. The Adelaide Observer reported in 1893 that the students “do well at the matriculation examinations of the University of Adelaide”, and many prominent local doctors and lawyers were products of the Hahndorf College.

It was a well—equipped school by any standards, roomy, attractively situated, with small classes and a relatively large staff. From all accounts, the boys enjoyed their time at the college, and stories are still current of some of their escapades. Boarders, for example, would often creep out of their dormitory at night, slide down a balcony post and steal across the road to Charlie Sonnemann’s bakehouse. Here they would help Charlie mix the dough and finish up by eating German cake, washed down with coffee.

The outbreak of the first world war abruptly ended the amicable mingling of German and English elements in Hahndorf (temporarily renamed Ambleside) as elsewhere in South Australia. This, as well as 'family affairs and the increasing competition of the State’s first higher educational institutions, finally determined Mr. Byard to close the college in 1916. He retired to England, where he died at the ripe age of 90.

The story of the next 50 years, during which the academy successively became a hospital, offices, and a private dwelling, is one of vicissitudes and gradual decay. After the death of the last owner, the building was put up for auction, and its fine corner site in the centre of the township on the main Adelaide—Melbourne highway attracted the interest of a petrol company. Only the concerted action of several prominent South Australian citizens, the generosity of an Adelaide master builder, and the petrol company’s magnanimous withdrawal from the sale saved it from destruction. But whether this was merely a stay of execution only the future can show.

In 1961 the Hahndorf Academy Museum Trust was founded and incorporated in South Australia under the chairmanship of Dr. Derek van Abbé, then head of the department of German in the University of Adelaide. The aim of the trust, whose secretary is Miss Josephine Heysen, Sir Hans Heysen’s granddaughter, is to restore the building to such a shape that it will be able to take its place worthily among the historic monuments of South Australia, and to make it a museum of local German and English antiquities and early South Australian history.

With its commanding site and its spacious rooms the Academy is ideally suited for this and other cultural purposes, while Hahndorf itself and its neighbourhood retain much of historic interest. The township, with its many small holdings, quaint cottages, and tree-lined main street preserves much of its original character. St. Michael’s churchyard boasts some fine ornate tombstones with German inscriptions, while the interior of St. Paul’s is like that of a typical German village church. Not far from the old windmill, about two miles beyond Hahndorf, is the unique hamlet of some half-dozen German-style farm houses at Paech Town. With their low fringed roofs and brick-and—timber walls the houses look as if they had been transplanted bodily from those central German villages whence Mr. Paech and his fellow—pioneers migrated 125 years ago.

With its commanding site and its spacious rooms the Academy is ideally suited for this and other cultural purposes, while Hahndorf itself and its neighbourhood retain much of historic interest. The township, with its many small holdings, quaint cottages, and tree-lined main street preserves much of its original character. St. Michael’s churchyard boasts some fine ornate tombstones with German inscriptions, while the interior of St. Paul’s is like that of a typical German village church. Not far from the old windmill, about two miles beyond Hahndorf, is the unique hamlet of some half-dozen German-style farm houses at Paech Town. With their low fringed roofs and brick-and—timber walls the houses look as if they had been transplanted bodily from those central German villages whence Mr. Paech and his fellow—pioneers migrated 125 years ago.

To preserve the Hahndorf Academy and to make visitors and residents aware of these treasures in South Australia are worthy aims and not unduly ambitious. But public support has been lukewarm, and the State Government has hitherto shown little interest in the Trust’s efforts. Only the generous interest and encouragement of the German Embassy in Canberra, to whom the project seems a valuable way of cementing German—Australian friendship, have so far saved the Trust from shipwreck. But time, weather, public apathy and the opposition of local philistines are formidable adversaries. If the Hahndorf Academy is to be saved for the edification of future generations there is not much time left to lose.