Drawing of Phylena McMaster by her daughter Mildred Blanchet

Drawing of Phylena McMaster by her daughter Mildred Blanchet  Dr. Sidney Blanchet with Lena McMaster

Dr. Sidney Blanchet with Lena McMaster  Lena McMaster at her favorite past time

Lena McMaster at her favorite past time

Died: September 3, 1916

Children: Two sons and Mildred McMaster Blanchet

Phylena "Lena" Jane Gray McMaster was Mildred Blanchet's invalid mother; she came to 27 Church Street (now 49 Church Street) in Saranac Lake to live with her daughter and Dr. Sidney Blanchet December 1, 19111 after her husband's death. Very likely she had to follow her newlywed daughter to Saranac; she was entirely dependent on her.

She had a severe case of rheumatoid arthritis and could not walk or use her hands; she was addicted to the morphine she used to mitigate the pain and experimented with bee stings (apitherapy) for rheumatism, reading up on Fanvre the entomologist about it. Perhaps her morphine addiction influenced Dr. Lawrason Brown's opinion; he was a close friend of the family. She and Mildred would sit on the porch in Saranac; she probably looked like a tuberculosis patient in her wheelchair on the porch, but she was not. Her daughter Mrs. Mildred Blanchet was the only one who could help her. Phylena, the practical frontierswoman, dominated Mildred the shy artist; only Mildred could put Phylena to bed. Phylena read voraciously, especially the Bible, history and biographies. She especially liked Teddy Roosevelt, the exuberant exponent of the Wild West who had left the presidency two years before she arrived in Saranac. She disliked the British - still fighting the Revolutionary War. She died at 27 Church Street in 1916 with her son in law as attending physician,2 but was not buried in a Saranac Lake cemetery.

Phylena 'Lena' McMaster with her daughter Mildred Blanchet in Saranac Lake

Phylena 'Lena' McMaster with her daughter Mildred Blanchet in Saranac Lake

Phylena Jane Gray was from a poor family of lumberjacks living in an impoverished wilderness area of northern Maine ravaged by forest fires; the family emigrated from there to one of the toughest hard-drinking frontier lumbering areas of the West. They moved often, chasing the supply of virgin timber and were often in debt. Her father Irving Gray was a hunter, rafter, hack driver, ran an all male lumberjack boarding house and a railroad worker boarding house, and her brothers and uncles were hack drivers, lumberman, in the liquor business or ran hotels in frontier towns – which were likely also saloons. It was not a quiet, civilized life.

Perhaps this was why 18 year old Phylena married a quiet man, son of a devout Presbyterian Scotch Irish immigrant; and why she saw her shy, artistic daughter Milly as less than grounded and practical; and why she said she “wanted nothing to do with those people” - her own family, the Grays. She had seen so much rough life that almost nothing could shock her.3

Phylena 'Lena' McMaster with her daughter Mildred Blanchet probably in Saranac Lake

Phylena 'Lena' McMaster with her daughter Mildred Blanchet probably in Saranac Lake

She was born in 1845 in a wilderness hamlet of 320 people called Wesley, Maine, on the Maine frontier, 30 miles from Canada. The area is not good farmland, and there was difficulty attracting settlers in spite of government promotion.4 Wolves still attacked settlers in Wesley when Phylena was growing up.5 The only industry was logging, but one of the biggest forest fires in North America, the Miramichi fire, had wiped out 1,000,000 hectares of forest in the area. The people lived by hunting, fishing, lumbering in the winter and farming in the summer. (Today, in 2012 Wesley is still tiny, still below the poverty line, and still living by hunting, fishing and logging.)

Migration to Lumber Towns of the West

Wesley was already poor, but the nationwide economic panic of 1837 was followed by several years of depression, as well as by local public land speculation in Maine. Almost every head of family in Phylena’s extended family was sued for debt in those years, including her father. Phylena’s uncle Sheldon Jr. sued all the inhabitants of the town for a $35 bounced check he received from the municipality for repairing a bridge, just before he left town to go out West.6

The town began to empty out in the second half of the 1800s. In 18497, when Phylena was four years old, her family and her uncle Sheldon's family moved to Chippewa, Wisconsin. Soon afterwards, more than 30 members of their extended family followed them to the lumber areas of Wisconsin and Minnesota.

They likely took about 11 days en route,8 perhaps going by steamboat from the nearby port town of Machias to Boston; by rail from Boston to Albany; New York canal boat from Albany to Buffalo; steamboat from Buffalo to Toledo, Ohio; by rail from Toledo to Chicago; by stage from Chicago to Galena, Ill.; by steamboat from Galena to St. Paul, Minn. Sometimes the boats up the Mississippi were fired on by the Indians in these years.910

The Chippewa River Pinery and the Wild West

Irving and Sheldon Gray moved their families to the Chippewa River Pinery in Wisconsin. Shortly after Irving arrived a drunken Indian shot his hat off his head. 11 This was a prosperous, rowdy frontier boomtown, where fortunes were made in lumber and civilization was far away. For a short time it was the biggest lumbering area in the world, until the pinery was depleted.12 Game was abundant; Indian tribes were more concerned with fighting one another than the white man; and hard drinking bachelor lumberjacks would rather shack up with Indian squaws than marry. The area depended on the river to carry the logs; but the river often flooded them out.

Phylena’s future brother in law Joseph McMaster, en route to the area in 1857 from Pittsburgh, wrote his brother Thomas,

“By the way, I hear a very bad character of Reed’s Landing from different persons who have been there. I saw a man from Fulton City, Illinois who was up there in the fall. He said he was never so much disgusted with any place before – there was so much drunkenness, gambling, and fighting – drunk Indians staggering about in every direction. A Mr. Taylor, of Allegany (Pennsylvania), who was out there, and stopped three days at Reed’s Landing since you have been there, says it is the most wicked place he was ever in – nobody can speak three words without swearing. He purchased land 4 miles from you on the Wisconsin side, and is going to settle there this spring.”13

Both the correspondents in this letter, Joseph and Thomas, died young, drowned in the Mississippi at Reads Landing, Minnesota, while celebrating the first edition of their newspaper, six years before Phylena married their brother.

The lumberjacks and rafters in the area stoned a preacher giving a sermon;14 whiskey was considered a staple food, along with pork and beans;15 wearing a dress shirt was considered a novelty and cause for gossip.16

They used to have a dances with fiddlers, and Phylena remembered séances after the dance - spiritualism was important to them. In the 1850s, it was the custom in Dunn County, Wisconsin, to have winter dances where men outnumbered women by three to one and attendance was compulsory for women. A dozen different languages could be heard, also gunplay; the women included full-blooded Indians, French Canadian women, often half-breeds, and white women.17

Trips to the public land office in Hudson, Wisconsin, were family events; Phylena's father, grandfather and uncle all have homestead papers with the same dates.18 They were probably lumbering with farming as a sideline, and possibly speculating in land. Irving's land was not good farmland, and he was working as a rafter floating logs down the river for the lumber company at the time. 19 Phylena’s uncle Aaron and her insane aunt, Mary Jane Blake Leathers, lived in the same town on the Mississippi, North Pepin.20 Aaron lost an election for justice of the peace;21 was sued and convicted for debt,22 and died of consumption (tuberculosis) a week after his conviction.23 His wife was interned in the Vernon County Insane Asylum as soon as it opened, and spent the rest of her life there.24

Indian war parties traveled through bent on attacking their traditional enemies until 1862, 25 but generally did not attack the whites. Hunting was unusually good for the whites that came early because Indians did not hunt in this no man’s land between the tribes. 26

“In the summer of ’57, the Chippewas made two Sioux braves bite the dust near the same locality, their heads were cut off and set on poles, their faces ‘ghastly grinning’ by the road, where it crosses Rock Run in the town of Wheaton.” 27

Wheaton was 15 miles from where Phylena was living at the time in Iron Creek, Dunn County, Wisconsin, a hunting and lumbering area with a total population of 96 people.28 Today, in 2012, Iron Creek is next to the Muddy Creek State Hunting Grounds.

Phylena Gray McMaster told her daughter Mildred that if the Chippewa Indians came through on the warpath with the Sioux they didn't worry - but when they came back drunk, the children would hide. The Indian women would help with childbirth, and she liked them, but not the Indian men. By the time Phylena was 18, she had delivered babies by without help. She remembered pouring bullets for her father, who often lived by hunting and fishing. She said as children they would go off in the woods with boiled potatoes and salt pork, and that there always things to eat in the woods, such as berries or nuts. 29

In about 1859, Phylena, a young teen, must have been living in the all male Carson and Eaton lumberjack boarding house in Eau Galle, Wisconsin. Her father was running it,30 and she was later called on to testify that Irving’s boss, William Carson was living with Susan DeMarie (Demerrer) Lamb, daughter of a French Canadian trader and an Indian medicine woman, although they were married to other people. Phylena told her daughter Mildred Blanchet that Carson sent his two half-breed children to college.31 The court excluded the half breed childred from the will. 32

Men in the area often lived with Indian women without marrying them. “The influx of white women in 1855-6, induced almost everyone to discard these women.”33

In 1860, Phylena moved with her mother and siblings to her live with her grandparents, uncles, aunts and cousins while her father continued to run the Carson and Eaton boarding house 70 miles away.34 Perhaps Irving was living apart from his family for lack of money. He was convicted of debt in 1857 for the amount of $158 and did not appear to oppose the charge. On the 1860 census Phylena’s parents are listed as Olive and “David Gray.” Perhaps her mother took up with David Gray and the couple was estranged. Phylena probably got her first schooling then; she mentioned that she was much taller than the other schoolchildren when she finally got to school. It's possible that her parents had Phylena go north because of the danger of rape at the logging camp; or because they wanted her to go to school.

In 1863, at 18 years old, Phylena married Hugh McMaster, an immigrant from Belfast, and then deliberately lost track of her own family. Two of Hugh’s brothers wrote emotional poetry, two others were newspaper editors, the father was very devout, and a sister was interested in history.35 Hugh himself had a quiet bent for the theater and was in the Minnesota Legislature. It's likely that such an interest in the arts, literature and religion was unusual in the frontier town and a contrast to her own family; the Grays continued to follow the virgin timber to new frontier towns in Minnesota, Idaho and Washington state, and were hack drivers and hotel keepers. Her brother, Milton, "in the liquor business," died young of tuberculosis.

Married Life

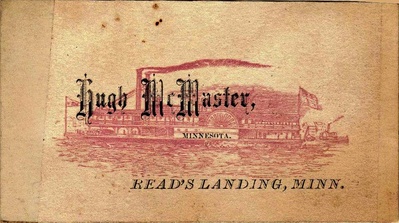

Hugh McMaster's business card. It shows a steamboat in the background.

Hugh McMaster's business card. It shows a steamboat in the background.

Hugh and Phylena’s married lives mirrored the lumber boom. During the heyday of Read’s Landing, Minnesota’s steamboats from 1862 to 1880, Hugh was a clerk on the steamboat ‘Silas Wright’, then a steamboat captain, and later ran the lumber company dry goods store in Reads Landing. When the lumber transport changed from steamboats to railroads they moved to Eau Claire, Wisconsin where Hugh was joint owner of McMaster, Snodgrass & Co, a dry goods company. And finally when the lumber was gone at the turn of the century they moved to Washington, D.C. Mildred, the third child, was born in 1885, when Phylena was 40 years old, and the difference in age made her parents seem like grandparents. When Hugh had a stroke they moved to Chicago.

It must have been difficult for Phylena when Mildred became sick with tuberculosis. Not only was Mildred her only daughter, but Mildred had been her nurse since she was 13, and Phylena's brother and uncle also died of tuberculosis. But Mildred was lucky; she went to Saranac Lake for a successful cure and fell in love with another patient who later became a doctor there. After Phylena's husband Hugh died Mildred and Phylena moved to Saranac Lake permanently.

Comments

Footnotes

1. Phylena McMaster death certificate #167

2. Phylena McMaster death certificate #167

3. Jeremy Blanchet interview with Mildred McMaster, about 1972, at Elizabeth Carleton House, Roxbury, MA. Mildred mentioned that nothing could shock Phlyena in the context of a conversation about sex.

4. http://www.oldcanadaroad.org/william_bingham/binghams_purchase.html viewed Dec 2012

5. “A Comprehensive History of the Town of Wesley”, Maine, page 2 unknown author, before 1972, photocopy provided by Town of Wesley to Jeremy Blanchet, 1972.

6. State of Maine court files, no #8085 Gray Jr. vs Inhabitants of Wesley, Sept 1949, Washington County, Maine.

7. US Federal census 1850 Chippewa, WI

8. The Day Genealogy, a record of the descendants of Jacob Day and an incomplete record of Anthony Day, Second edition. Published 1916 by The Warren press in Boston, Mass page 126 http://www.archive.org/stream/daygenealogyreco00daya#page/251/mode/2up Reference found through Stephen Robbin’s document

9. The Day Genealogy, a record of the descendants of Jacob Day and an incomplete record of Anthony Day, Second edition. Published 1916 by The Warren press in Boston, Mass page 153 http://www.archive.org/stream/daygenealogyreco00daya#page/307/mode/2up Reference found through Stephen Robbin’s document

10. Note: Mildred McMaster Blanchet told Jeremy Blanchet that her mother went west via covered wagon, but this is unlikely.

11. Jeremy Blanchet interview with Mildred McMaster, about 1972, at Elizabeth Carleton House, Roxbury, MA.

12. Antenne, Katharine Leary / A saga of furs, forests and farms : a history of Rice Lake and vicinity from the time of its first inhabitants : the Indian mound builders to the turn of the 20th century (1955 (1987 reprint)) page 24

13. From a letter from Joseph McMaster to Thomas McMaster 1857, Minnesota Historical Society

14. History of the Chippewa Valley, Thomas E. Randall 1875, Eau Claire, WI page 44 http://www.archive.org/stream/historyofchippew00rand#page/44/mode/2up

15. History of Northern Wisconsin, 1881, pg 275 http://www.archive.org/stream/historyofnorther00west#page/274/mode/2up

16. The American Sketchbook, Menomonie and Dunn Counties, 1875 by Bella French page 274-275 http://www.archive.org/stream/menomoniedunncou00fren#page/274/mode/2up

17. History of the Chippewa Valley, Thomas E. Randall 1875, Eau Claire, Wisconsin, page 65-66 http://www.archive.org/stream/historyofchippew00rand#page/64/mode/2up

18. US General Land Office Records, accession number WI0450.240 All retrieved Feb 14, 2012 - Irving Gray: http://www.glorecords.blm.gov/details/patent/default.aspx?accession=WI0430__.003&docClass=STA&sid=b4k1uhob.oxo Sheldon Gray: http://www.glorecords.blm.gov/details/patent/default.aspx?accession=WI0430__.454&docClass=STA&sid=aeqhr1li.5er Gideon Gray: http://www.glorecords.blm.gov/details/patent/default.aspx?accession=WI0420__.280&docClass=STA&sid=33md42ev.s5jon

19. History of Dunn County, page 523-524 Wisconsin Curtiss-Wedge, F.; Jones, Geo. O. (ed.) 1925 Retrieved Feb 14, 2012 http://digicoll.library.wisc.edu/cgi-bin/WI/WI-idx?type=goto&id=WI.IHDunnCounty&isize=M&submit=Go+to+page&page=523 and http://digicoll.library.wisc.edu/cgi-bin/WI/WI-idx?type=turn&entity=WI.IHDunnCounty.p0730&id=WI.IHDunnCounty&isize=M

20. Federal census 1860

21. The Pepin Independent, 1859 04 08 Elections

22. Pepin County Court Records, 1876

23. A Leathers death notice Pepin County Courier April 18, 1879

24. Federal census 1900 and 1910; Find a Grave Memorial # 80231613 retrieved Feb 14, 2012 http://www.findagrave.com/cgi-bin/fg.cgi?page=gr&GRid=80231613

25. History of Minnesota, Volume 1 By William Folwell pg 259 History of Minnesota, Volume 1 By William Folwell pg 259 on google books

26. History of the Chippewa Valley, Thomas E. Randall 1875, Eau Claire, WI page 15 http://www.archive.org/stream/historyofchippew00rand#page/14/mode/2up

27. History of the Chippewa Valley, Thomas E. Randall 1875, Eau Claire, WI page 75 http://www.archive.org/stream/historyofchippew00rand#page/74/mode/2up

28. 1855 Wisconsin census

29. Jeremy Blanchet interview with Mildred McMaster, about 1972, at Elizabeth Carleton House, Roxbury, MA.

30. History of Dunn County, page 523-524 Wisconsin Curtiss-Wedge, F.; Jones, Geo. O. (ed.) 1925 Retrieved Feb 14, 2012 http://digicoll.library.wisc.edu/cgi-bin/WI/WI-idx?type=goto&id=WI.IHDunnCounty&isize=M&submit=Go+to+page&page=523 and http://digicoll.library.wisc.edu/cgi-bin/WI/WI-idx?type=turn&entity=WI.IHDunnCounty.p0730&id=WI.IHDunnCounty&isize=M

31. Jeremy Blanchet interview with Mildred McMaster, about 1972, at Elizabeth Carleton House, Roxbury, MA.

32. Eau Claire Leader, August 13 1898 "End of the Carson Case"

33. History of the Chippewa Valley, Thomas E. Randall 1875, Eau Claire, WI page 66 http://www.archive.org/stream/historyofchippew00rand#page/66/mode/2up”

34. 1860 Federal census

35. The Waumadee Herald, May 1857 lists the McMasters as editors.; poem from the McMaster brothers from Jeremy Blanchet; photo of Hugh McMaster as an actor; Clara was a contributing member of the Minnesota Historical Society.