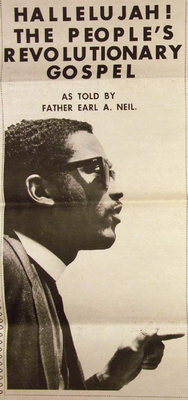

The People's Revolutionary Gospel was an interview with Father Earl A. Neil, published in the December 20, 1971 edition of The Black Panther newspaper.

Father Earl A. Neil, of Saint Augustine's Episcopal Church in Oakland California, has become a well-known figure, over the past few years, particularly. Although he has been recently placed in a high-ranking position within the Episcopal Church, and has been a strong and righteous voice defending the rights of oppressed people, he has been called by the racist U.S. power structure everything but a child-of-God. The following, recent in-depth interview with Father Neil, reveals why this is so, for he has practiced what he preached:

Q: Father Neil, could you tell us something about your background, where you're from, and how you came to be a minister?

FATHER NEIL: I was born and raised In St. Paul, Minnesota and I grew up there, went through the public schools there; graduated from Carleton College in Northfield, Minnesota, in 1957, and graduated from Seabury Western Theological Seminary in 1960. My first church was in Wichita, Kansas, My next church was in Chicago, and from Chicago I came out here (to California). I've been out here for four and a half years now.

Q: When did you become actively involved in the civil and human rights struggle, and would you describe that period?

FATHER NEIL: Actually, I first became involved in the human rights and civil rights struggle when I was 7 years old, when my mother and father got me out on a picket line, picketing the grade school. I was in the second grade at that time. And, as I look back on It now, I know now what was going down. There were rather deplorable conditions at that time; that was back in around 1942. And so I got involved actively in the struggle when I was 7 years old. They were picketing the school back then, even; and that's in St. Paul, Minnesota (of all places). Then, during the time I was in high school and in college, I was very much involved with the local NAACP. At that time that was the only civil rights organization in existence. My involvement continued through the time when I was in the Seminary. When I was in Wichita, Kansas, I worked with the NAACP there.

When I went to Chicago, that was back in 1964, I got involved in the civil rights movement in the South. During the summer of 1964 I worked with an organization called COFO (Council of Federated Organizations), which was an organization brought about by the combined efforts of SNCC, CORE and state civil rights groups in the State of Mississippi. They were combining their efforts in a voter registration drive in the South at that time. The place where they were having the most difficulty was in Southwest Mississippi, in a place called McComb, Mississippi, which is about 60 miles southwest of Jackson. That place is so bad that even James Eastland doesn't even bother to campaign there, because folks are just so out of sight and so blinded by their racism. In McComb, during the summer of 1964, there were at least 28 bombings and burnings of homes and of churches. It was considered the most dangerous area in the South, and, indeed, in the State of Mississippi at that time.

COFO sent out a call for people from around the country to come and help in voter registration efforts there. I was one of the persons who responded to that call, and went down there. It was a very educational experience for me, and somewhat of a turning point to my own life. For then I really saw, first hand, just what the conditions were in the South; and it was just like another country. It was the first time the I ever felt completely helpless, and didn't know where to turn, I me fin that it really came down on me, the conditions were just that critical.

This was first brought home to me when the plane landed in Jackson and my travelling companion, another priest, and myself went to the motel where we were staying. The first thing we did was to call the FBI to let them know we were there. And, the FBI made a very ominous statement to us, and pointed out to us that if anything happened to us, we understood, of course, that they could not step in, unless there was a violation of civil rights. In other words, if we got offed while we were down there, they could do nothing to prevent this. They could only step in after some action had happened. Then, after telling us, they said, "Now will you please give us the names of your next of kin". This was a very devastating thing to me, because I know that if anything did happen there, you could not appeal to the city police, the county police, the state police or to the FBI, because for one thing they're all part and parcel of the same racist, oppressive operation in the United States. As I was saying this was the first time I really felt hapless and powerless; and I was very, very frightened.

Well, if I was frightened, the people In McComb were ten times as frightened, because they had to live with this fear, with these conditions, all the bombings and burnings (which were particularly numerous during the summer) all through their lives there. This has been the situation, with the White Citizens Council and the Klan running through the Black communities, trying to destroy them.

While I was in Mississippi, on August 28, 1964, the Society Hill Baptist Church was bombed. At this church mass meetings had been held during the summer, trying to get people out to citizenship classes, and trying to get them out to register to vote. The church had been used for this purpose, and, as I mentioned, on August 28, 1964, the church was bombed, at about 11:30 that night; and about half an hour later, the home where this other priest and I were staying was bombed.

Q: Was it the home of a local resident?

FATHER NEIL: Yes it was. It was the home of Mrs. Alyene Quinn, Mrs. Quinn was one of the few Black people who did have the courage to come out, openly identify with the civil rights workers at that time. This is not to say that the other Blacks did not have that courage; but she was just one of the few Blacks who actually stepped out and was identified as one of the local leaders in Mississippi.

In the citizenship classes that we held, we schooled the citizens on how to take the voter registration tests and how to vote, and so forth. Another thing which stood out in my mind and made a great impression on me when I was in McComb is when we went around door-to-door in the Black community to canvass the people. Some of the people, as soon as they saw us, knew what we were there for, and they would not let us in. Some people would. There was one house we went to, there were about 5 Blacks sitting on the front porch. This other preacher and I went up to it, and we started talking with them, just exchanging courtesies with them, and what have you. As soon as we said we would like for you to come out to the citizenship classes, they all got up off the porch and went into the house. That was testimony to me. It showed me how paralyzed with fear the people were.

One final point about McComb, that has not been brought out, and it's true of the whole civil rights struggle, that in McComb the Black community there, because of the bombings and burnings that had gone on there, the Black community armed itself. They made that decision. They armed themselves to defend their community against these night riders. And the philosophy they operated on was: ''You have to bring your life to take mine." And this is a thing that was not pointed out. This was a fact of the civil rights movement in 1964 that has not been brought out in literature or in writings about it. And it's significant, too, that in the very next year, in the spring of 1965, the Deacons for Defense and Justice came out. This was the first Black group in this century that stood up and came out publicly and stated that they would defend with weapons the lives of the community, and the property of Blacks and the community. And this is not an attitude or position that they came to overnight. This has been a history in the South; and I think that it's important to bring that out about the struggle.

Q: That even back in 1964 an entire community armed itself?

FATHER NEIL: Right, for self defense.

Q: Even though they used the tactic of non-violence, etc.?

FATHER NEIL: Correct, because they knew that the power structure would respond to the peaceful, non-violent picketing with violence. So the idea was, when you respond to them with violence, we're going to defend their lives.

Q: We could say, then, that Malcolm X did have quite a far-reaching effect, even though we hadn't heard about it or weren't aware of that effect, when he said defend yourself?

FATHER NEIL: This is true. Also, not only Malcolm's brilliant teaching and brilliant analysis of the scene in America, but also the life conditions of the people, even those Blacks who hadn't heard of Malcolm, the life conditions were enough to educate the people that this was the stance that they had to take.

Q: Would you describe your work with the Reverend Martin Luther King and the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC)?

FATHER NEIL: I first came into contact with Dr. Martin Luther King in the early spring of 1965, in the incidents leading up to the Selma to Montgomery march. In Selma, Alabama, SNCC (Student Non-Violent Coordinating Committee) in response to the shooting of Jimmy Lee Jackson, up in Monroe County, SNCC had talked with the local residents. They felt that in order to point out that Jimmy Lee Jackson had been killed because of his efforts to organize the Black community to voting, that there should be a march starting in Monroe County, where Jimmy was killed, going through Dallas County (where Selma is), on through Lowndes County, and on to the Montgomery County, where the state capital is, to dramatize the need for Blacks to register to vote, the need for a voting rights bill and the fact that Blacks like Jimmy Lee Jackson were being murdered because they were trying to exercise their rights. SNCC was joined by the SCLC in this effort. On March 9, 1965, was the first attempted march from Selma to Montgomery. Of course, we know the history of that atrocity that went down. People were beaten, tear-gassed, ridden down by mounted police, and so forth. Well, right after that, Dr. King issued a call for people from around the country to come and join in this march to Montgomery, and I went down there. I worked for the SCLC, and the responsibility that I had for them was that I was in charge of the orientation of all the people who came to Montgomery to march. The orientation consisted of, literally, how to survive while you were in the South; what things to do and what things not to do; and how to protect yourself; and so forth. It was during this time that I got to know Dr. King, through working with SCLC. Then, the next year, in 1966, Dr. King and SCLC went to Chicago to point up the housing and poverty conditions of Blacks in Chicago; and there I worked along with Dr. King and SCLC also.

Q: Were you in Cicero, Illinois, when they were marching for open housing conditions?

FATHER NEIL: Right. There were different areas in Chicago where we were marching for open housing. Some were Marquette Park, Gage Park, South Deering (these are some of the notable places, where the most dramatic, most violent responses of the whites in Chicago took place). It was toward the end of the summer of 1966 that an open housing march was attempted in Cicero. However, a march did not take place, because there was such a violent response on the part of the people in Cicero.

Q: You have been described as the "Panther Cleric" and "Huey P. Newton's Spiritual Advisor". When and how did you become involved and associated with the Black Panther Party?

FATHER NEIL: As I mentioned earlier I came out here in July 1967, and back in Chicago I had heard about the Black Panther Party. When I got out here, I heard about it, of course. This is where it was organized. I spent the last 6 months of 1967 feeling my way around the scene here. Then, around February, 1968, I began visiting Huey at the Alameda County Jail. He was there having been arrested for the alleged shooting of some police officer in West Oakland (I can't recall his name. It's not important.) At any rate, I was visiting Huey in Alameda County Jail. Shortly after this, toward the end of 1968, when Bobby and David and several others were busted on this alleged illegal weapons charge, conspiracy to do something, after one of the hearings that Bobby had to go to up in Berkeley, I let David know that if the Party ever wanted a place to meet, to feel free to meet at St. Augustine's Church. That was on a Tuesday. The very next night they had a meeting down at the church. From that point on, that's where my actual association began, and, as far as I'm concerned, has beautifully developed, because I'm very flattered to be allowed to continue the relationship with the Party. I'm glad the Party has allowed me to do this.

Q: Could you tell us why you have continued to work so closely with the Party?

FATHER NEIL: Well, number one, I relate very much with the 10-point program. As I read the scene with Black people across the country, I believe that the Black Panther Party has the most incisive analysis and response to the scene in America.

As I suggested earlier, the mood of Blacks around the country was changing (in 1968), the response of Blacks to the racism and oppression of this country. We saw that the powers-that-be did not respond to non-violence, so Blacks were forced to take another stance. The Deacons for Defense and Justice during that time also survived. Of course, we had the street rebellions of Watts, and so forth, and Blacks were standing up and trying to find a way to respond to the oppression that they felt and lived with day by day. The Party, very simply, as I understood the Party, was saying we want to put these programs into operation; and it's been the case, historically, whenever these programs have been put into operation, the military has been sent in to stop them. The Party is saying that whenever the military is sent in, Black people will defend themselves, as we have, because we can have no defense from any other place... And, I felt that the Party was in the vanguard of this response.

I knew that the Party would be getting a lot of misunderstanding, a lot of flak, which it still continues to do. However, I believe in the way the Party has moved, and, through my own observation and my own experience. Plus, I love the brothers and sisters in the Party. There are a lot of beautiful brothers and sisters in it.

Q: With what other organizations are you presently involved, and what is your work with them?

FATHER NEIL: I am a member of the Alamo Black Clergy, which is an interdenominational group of Black clergy in the Bay Area (Northern California). One of the things that we try to do is we try to show the role that organized religion has, as far as the Black Liberation Movement is concerned.

I'm presently the Chairman of the Bay Area Union of Black Episcopalians. This might be referred to as a Black Caucus within the Episcopal church here in California, What we're doing is we've organized Black Episcopalians to lift up and try and change the racism that the Episcopal Church perpetuates in many areas: Be it in employment; be it in curriculum; be it in business investments; and so forth.

I'm also Chairman of the Bay Area Ad Hoc Committee on Grand Jury reform. And, I'm just a member of the community, in general; whatever groups want, if I can be of assistance to any kind of groups that function in the community.

Q: At one time you were a member of the Alameda County Grand Jury. From your direct experience, could you give us your opinion of the workings of the Grand Jury and why so few Black and other poor people are selected for Grand Jury duty?

FATHER NEIL: I was on the Alameda County Grand Jury in 1970. And one reason why there are so few Blacks, poor and young people on the Grand jury is because of the way the grand jury is selected. Briefly I'll describe that. Each of the superior court judges (there are 25 in number) nominates 2 people, known to them, to be on the grand jury. This means they may just nominate two of their friends. They might be members of their local John Birch Society, their local Minutemen society, their local Kiwanis, local Lions, local Rotary clubs, what have you, and this is 50 names. From these 50 names, 30 names are drawn (allegedly at random) to be a grand jury candidate. Then, a second drawing is held, again allegedly random, from which 19 names are drawn to complete the grand jury. The remaining ll names are substitute grand jurors. 'In case the 19 drawn cannot continue to function, they would be replaced from the 11.

It's interesting that in the 1970 drawing on the panel of 30, there were 6 blacks; 5 of us were drawn. Blacks have never enjoyed those odds before. Five out of 6 were drawn on the 1970 grand jury. Another interesting thing is that during the year, one of the Blacks and one white had to leave the grand jury, because they had moved out of town. They went back to the remaining panel of jurors, and they drew one white name and the remaining Black. Those odds were quite remarkable. That's why I say the drawings are allegedly at random. This year, I believe, there were one Black, one Chicano and two or three Orientals, So, 1970, in my opinion, appeared to be the year for the Blacks. But anyway, the reason that so few young, Black and poor people are on is because the judges do not nominate people from these constituencies. They say that they don't know any, which may or may not be the case. This is why it is so important that community groups of these constituencies (of the Blacks, young, poor and other ethnic minorities) submit names, to the superior court judges, of people who would be willing to serve on the grand jury, since they say they do not know of anybody like this. It is perfectly legal and perfectly all right to do it this way, for groups to submit names to the judges, so that their names may be placed in the hat.

One other reason that there are few ethnic minorities on the grand jury is that the time involved is tremendous. It takes about 3 days a week, and the pay is only $5 a day and most working people do not have the time; nor do they have the kinds of jobs that would allow them to take 2 - 3 days off during the week; nor is the pay that they get from serving on the grand jury commensurate with their salaries,

However, there is no reason why people on welfare should not be allowed to serve on the grand jury. They have both the time, and, if they're getting their welfare allotment, they don't have any worry about finances. The names of people on welfare very definitely should be submitted and that would take in a lot of folks, a lot of young people, a lot of ethnic minorities and a lot of poor people. So, the grand jurors would be chosen from that constituency, of those who have to receive public assistance. An argument leveled against this is that these people do not have enough expertise in business matters. Well this is a big hoax in my opinion, because anybody who has to receive public assistance knows that welfare department inside and out. Also, knowledge of business or expertise is not a prerequisite for a grand juror, because of the other folk who served on the grand jury. They didn't know their left foot from their right hand. They did not have that expertise at all. The only qualifications, as I see it, for a grand juror is that you have some kind of sensitivity to human needs, and just be a human being…

Q: You have recently been elected to a position on the Standing Committee of the Episcopal Diocese of California, Could you explain more about this and what it means to you and to the community, and would this position take you away from the work that you have been doing with community groups?

FATHER NEIL: I'll answer your last question first, No. It will not take me away, and I would not accept the position if it did; but, no, it would not, I might also say that it does not mean that I will have to leave St. Augustine's and move over to San Francisco or anything like that. I'm serving on the committee with no salary. I don't give up St. Augustine's or anything like that. It will not take me away from what I have been doing.

The Standing Committee is a committee of the diocese, something like the Central Committee of the Black Panther Party, in that it is the body that functions and makes important decisions involving the affairs of the diocese of California. Some of its functions are these: If the Bishop of the diocese, who is the head of the diocese, cannot function, he may be ill, he may retire, he may die, if the diocese is without a Bishop for any reason, then the Standing Committee is the committee that makes the decisions that he would in the diocese. That's one of its functions, one of its roles. Another function is that before a congregation or a church can venture into any huge financial obligation or contract, it must get the approval from the Standing Committee. Before a man can be ordained a priest in the church, he must come before the Standing Committee and be approved by them. Then, there are other administrative matters that the Standing Committee deals with. If some kind of difficulty takes place between a clergyman and his congregation, the Standing Committee will arbitrate that; some difficulty between the priest and the bishop, the Standing Committee will arbitrate that. There are other important decision-making policies the Standing Committee executes.

This is the first time, to my knowledge, in the history of the diocese of California that Blacks have been on such a committee. It's important in the sense that Blacks are finally in decision-making positions at that level. I'm just one of eight people on the Committee. There are some whites on the committee that are very sensitive and very human and very fine, Christian people. At any rate, it's the first time in history that Blacks have been in this type of decision-making process, Around the country, the different diocese around the country, each diocese [ has a? ] standing committee. Often times [ this is? ] not at this decision-making [ ?? ] is one of the things that our union raises, that although Blacks pay their assessments, our financial obligations to the diocese and so forth, we have no share in the decision-making process. So, this is a step, at least.

Now how this position can be used to benefit the community. I'll just have to rely upon the holy spirit of God to give me that direction; and if He can use me in this capacity, then, believe me, I will open myself up to it.

Q: Since you have known Huey P. Newton for some time now, this leads to asking your opinion of his last trial, in which another jury was unable to reach a decision?

FATHER NEIL: My opinion of the whole trial was that it was another step in the state's attack to deplete the financial and the emotional resources, and psychological resources, of the Party and the community. I do not view this past jury's indecision as a victory at all. The very fact that Huey had to go through a third trial was unnecessary, in my opinion. The second trial was necessary in the sense that the previous decision was reversed, but even that one (the second trial) wouldn't have had to have happened, if the judge, from the get-go, had done the correct thing.

Even if the verdict had come down 11 - 1, I would not think that this was a victory, because of the very fact that he had to go through that. And I think it was a waste of time, a waste of the taxpayer's money. I think that this should really be brought out. It was a waste of the taxpayer's money and all that money could be used for many other things. It could be used to improve conditions in the schools; for rehabilitation of men on probation or on parole; it could be used to improve conditions at Santa Rita or juvenile hall. There're many things that this taxpayer's money could be used for, rather than to financially support the personal vendetta of Lowell Jensen, et. al, on Huey P. Newton and the Black Panther Party. I view the inability to reach a verdict not as a victory at all, but as a defeat for justice in this country, in this county and the world, by the very fact that he had to go through it. No matter what decision they came out with, even if it was acquittal, the very fact that he had to go through this much stuff in order to establish his innocence is still an indictment on the criminal justice in this country.

Thank you very much Father Neil.

ALL POWER TO THE PEOPLE